Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945): from celebrated natural historian to obscurity

Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945) : d’un naturaliste célèbre à l’obscurité

- Steve O’Shea, Phil Eyden, Jonathan D. Ablett & Amanda L. Reid

|

Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945), a former Deputy Keeper of Zoology at the British Museum of Natural History, now Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom, passed away of natural causes in a psychiatric hospital at the age of 57. Despite his scientific authority, what little has been published about him is replete with error, or contradictory. By consulting surviving medical and military files, grey and peer-reviewed literature, museum correspondence, and public record documents, we present a more comprehensive picture of this man’s adolescence, World War I record, professional career, contribution to the study of natural history, illness that contributed to his admission into various psychiatric institutes, and those that contributed to his death. References to his declining mental health having influenced the quality of his research are critically evaluated and deemed to be untenable. An updated bibliography of his research output is presented, and one surviving and at least three presumed-lost, unpublished manuscripts are identified. Keywords: British Museum of Natural History – malacology – Cephalopoda – Octopoda – depression – bibliography Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945), ancien Deputy Keeper of Zoology [conservateur adjoint de zoologie] au British Museum of Natural History est décédé de causes naturelles dans un hôpital psychiatrique à l’âge de 57 ans. Malgré son autorité scientifique, les rares publications le concernant sont entachées d’erreurs ou se contredisent. En consultant les dossiers médicaux et militaires conservés, la littérature grise et évaluée par les pairs, la correspondance muséale et les documents d’archives publiques, nous proposons un portrait plus complet de son adolescence, de son parcours pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, de sa carrière professionnelle, de sa contribution à l’étude de l’histoire naturelle, ainsi que des maladies qui ont conduit à son admission dans divers établissements psychiatriques et, en fin de compte, à son décès. Les hypothèses selon lesquelles la détérioration de sa santé mentale aurait compromis la qualité de ses travaux sont ici examinées de manière critique et jugées non fondées. Une bibliographie actualisée de sa production scientifique est présentée, et des manuscrit inédits – un conservé et au moins trois autres présumés perdus – sont identifiés. Mots clés : British Museum of Natural History – malacologie – Cephalopoda – Octopoda – dépression – bibliographie |

Career, and research-community outreach (1911–1936)

Inaccuracies in obituary notices

Guy’s physical prowess (1903–1916)

Physical Health (1917–1918, 1936, 1944)

A marriage breakdown (1932–1933)

Institutionalisation (1933–1945)

Criticism of Guy’s research output (1977 onwards)

|

Nine days after Germany unconditionally surrendered in World War II, Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945), a personable and highly regarded malacologist and natural historian, passed away at Holloway Sanatorium, Virginia Water, in the United Kingdom. It was 17 May 1945, he was just 57 years old, and he had lived in institutions for the best part of eight years. Other than his passing having been “sudden” (Anonymous, 1945; Smith, 1945) or “after a long illness” (Hindle, 1945, 1946), of what he died and where his remains had been interred, if they had been, were unreported. Much of what little else has been published about him was similarly contradictory, incorrect, or not supported by evidence. To right an injustice done to his legacy, we build on what is known of this man, and correct inaccuracies in accounts of his life that resulted in the quality of his research being questioned. Born on 11 February 1888 in South Woodford, Essex, Guy was 5 foot 11.5 inches (~1.82 m) according to a military examination certificate, or 5 foot 9.5 inches (~1.76 m) according to his military enrolment papers. 1 Other than the frontispiece (plate 1) in vol 22 of the 1936 Proceedings of the Malacological Society, and an image of him in Hodgson et al. (2021: fig. 2C), few other images of Guy are known; we present one further (Fig. 1). He was evidently slim, wore spectacles, and had thinning hair into his 30s. He had been described as having an agreeable and pleasant temperament, “a characteristic thoughtfulness for dumb animals” and capable draughtsman, watercolourist, and etcher of considerable ability (Smith, 1945), to have had many friends (Anonymous, 1937a), and, according to his brother and only sibling, Selby Robson (1886–1964), to have been, at least as an adolescent, gregarious. 2 He was also described as being “a most skilled and entertaining lecturer” (Anonymous, 1932).

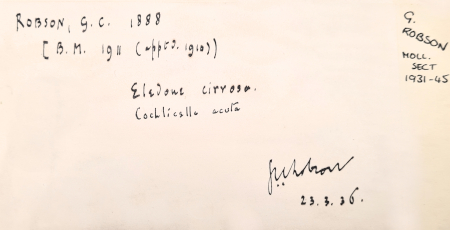

Guy reputedly began working for the British Museum of Natural History (BMNH), now Natural History Museum (NHM), London, in 1907 (Anonymous, 1945), 1910 (Anonymous, 1910a, b), 1911 (Anonymous, 1937a; NHM employment records), or 1913 (Hindle, 1945, 1946). The London Gazette (Anonymous, 1910a) announced that he started on 14 November 1910, but NHM employment records indicate this to have been 1 June 1911. His handwriting sample (Fig. 2) reveals that he officially began working for the BMNH in 1911, but that he was appointed to his position in 1910. Fresh from Oxford University, 22 years old, following his appointment to the BMNH and only having been recently conferred his Bachelor of Arts degree, Guy spent five months at the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn in Naples on an Oxford University Biological Scholarship (Robson, 1911). Upon his return he assumed his role at the BMNH, where he remained through to 1936. His tenure was broken only by service during and convalescence following World War I (WW1), and a period of uncharacteristic but recurring absences between December 1933 and November 1936.

Both Hindle (1945, 1946) and Smith (1945) maintained that Guy was home-schooled because of “delicacy as a child,” but from what age and what was meant by “delicate” is unknown. His brother indicated that his childhood was “normal.” 3 From 13 years age in September 1901 (Smith, 1945) to 18 years in 1906 he attended Forest School, Walthamstow (Anonymous, 1906a). No stranger to academic achievement, he secured a scholarship to attend Forest School (Anonymous, 1902) and thereafter was awarded prizes in classical subjects such as English, Roman and religious histories, general knowledge, poetry, and Latin (Anonymous, 1903; 1904; 1905a, b; 1906a, b). From 1905 to 1906 he was a co-Editor of the Forest School Magazine, and was also involved in theatre (Anonymous, 1904, 1906a). In 1905 he was awarded an unspecified Kings College prize (Anonymous, 1905b), and in 1906 received scholarship offers to further his education from each of Hertford, Wadham, Worcester, and New College constituent colleges of Oxford University (Anonymous, 1906a, b). At Oxford, Guy passed his Moderations (first public exam) in Classics with a 2nd in Lent Term of 1908, and, following a shift in academic interest, in June 1910 (Trinity Term) placed First Class in the Final Honours School of Natural Science and received his BA (Anonymous, 1910b). In early 1922 (Oxford University Hilary term) he was conferred an honorary MA (pers. comm. Michael Stansfield). 4 However, despite being highly intelligent, articulate, and occasionally referred to as “Dr Robson” by the press, colleagues (Anonymous, 1933), and even in the title of one obituary notice (Hindle, 1945), Guy lacked a PhD. Mathematics was a self-declared academic weakness (Anonymous, 1905).

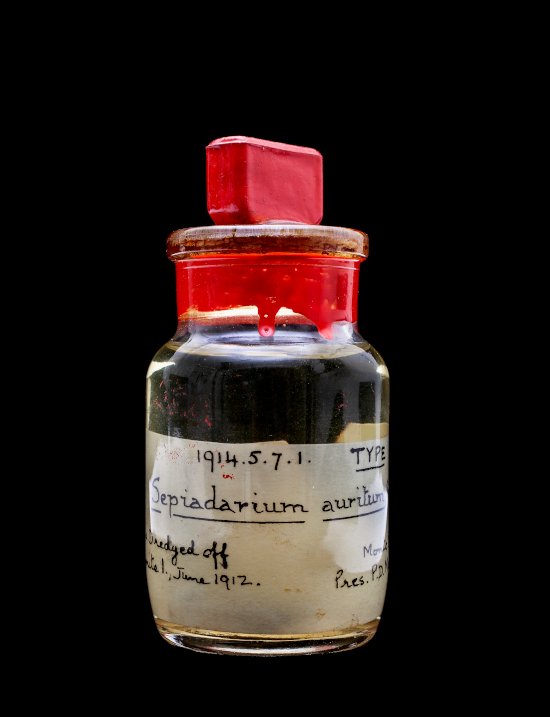

Guy, a prolific writer with diverse research interests, produced at least 116 mostly substantial publications. To teuthologists he rose to prominence for his works on octopuses and squids—a group of molluscs upon which he published no fewer than 55 papers and a seminal monograph in two volumes (Robson, 1929, 1932). To evolutionary biologists he may be better remembered, perhaps unfavourably (Huxley, 1942), for his works on defining species (Robson, 1928) or variation of animals in nature (Robson & Richards, 1936). To other malacologists, he may be known for his contributions to the taxonomy and anatomy of molluscs in general (land, freshwater, and marine; both fossil and Recent). A revised bibliography of his works (excluding Encyclopedia Britannica entries) that corrects errors in, and includes omissions from the account of Adam (1946), is presented as Supplement 1. A product of his Naples scholarship, Guy’s first paper (Robson, 1911) described how a parasite affected the sexual physiology of a crab. Several further papers followed, primarily on the taxonomy or anatomy of pulmonate gastropods, before he described his first cephalopod—a species of Sepiadarium from Australian waters (Robson, 1914) (Fig. 3). His next project, a description of a collection of Indian Ocean cephalopods, was completed and read on his behalf by Professor J. Stanley Gardiner (1872–1946) at a Linnean Society meeting on 17 June 1915, but its publication was delayed until after WW1 (Robson, 1921). Therein (loc. cit.: 430) Guy wrote “The author [Guy] has been struck, while in the course of this work, with the necessity for a more intensive study of these animals [cephalopods] for the purposes of systematic zoology.” From this it is apparent that Guy’s interests in both systematics and cephalopods were piqued from an early stage in his career.

Career, and research-community outreach (1911–1936) Between 1911 and 1925 Guy was promoted from Second-Class Assistant to Assistant at the BMNH (NHM records do not specify when); then to Assistant Keeper on 1 January 1926, and Deputy Keeper on 1 April 1931 (Anonymous, 1937a; NHM employment record archives). He also served as Secretary of the Challenger Society from 1921–1928 (CS, 1928, NHM archives), was a general committee member of same in 1929 (CS, 1929); was treasurer of the Society of Experimental Biologists from 22 December 1923 to 1926 (SEB, 1974); and from 1923 to 1924 was active in, and served on the editorial board of The British Journal of Experimental Biology (Erlingson, 2013). After serving as Editor for the Malacological Society of London from 12 February 1926 to 19 February 1928 he was elected its Vice President (19 February 1928) and then President (14 February 1930). An abridged biography is presented in Table 1. His period prominence and involvement in the research community is unquestionable. However, within years and at the pinnacle of his success, he all-but disappeared from the scientific community. We sought to understand why.

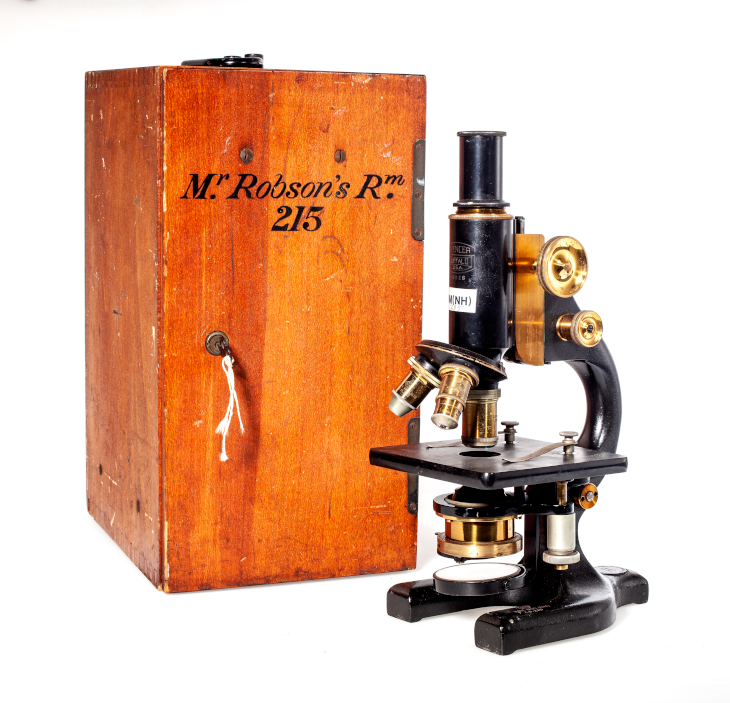

Table 1. Abridged biography of Guy Coburn Robson. Guy’s fixed-(three year)-term as President of the Malacological Society ended on 10 February 1933, whereupon he assumed the role of Vice President for three further years (to 14 February 1936). Because the presidency of this Society is a title held for three years only, 5 this change in status is uninformative. However, from early 1933 to November 1936, Guy’s research output also largely ceased, and from about 20 December 1933 to November 1936 he was frequently absent from work. The strain that his recurring and extended absences placed upon his colleagues, his having exhausted all forms of salaried leave, and his lack of productivity forced the museum to terminate his employment on 28 November 1936 on grounds of incapacity and Civil Service sick-leave regulations. 6 The final indignity to him occurred on 10 December when Martin Hinton (1883–1961), a newly appointed Keeper of Zoology, contacted his brother Selby, with whom Guy had been staying, 7 and asked if he could retrieve Guy’s remaining personal possessions from the museum, or otherwise advise the museum on how best to dispose of them. 8 Today, a microscope bearing his name remains (Fig. 4). In the lead-up to Guy’s dismissal, the museum acknowledged that his case deserved the utmost of sympathy, 9 but he had transitioned from being an esteemed staff colleague (Smith, 1945) to someone perceived to be a burden. Four days later, 14 December 1936, 10 Guy checked himself into Bethlem Royal Hospital (hereinafter ‘Bethlem’), where he resided until June 1944. On admission, he informed the attending physician that he had tendered his resignation from the museum (contrary to NHM archived correspondence 11) and that the museum’s acceptance of this had aggravated his depression. 12 The Kensington News and West London Gazette reported that Guy had “retired” from the BMNH (Anonymous, 1936b), and Anonymous (1937) wrote that he had “resigned,” but having being managed from his position, if this was the case, renders neither account strictly correct. As an aside, Guy’s NHM personnel file contains no resignation letter.

At least one of Guy’s peers had some understanding of his personal problems, for correspondence between Ronald Winckworth (1884–1950) and William Adam (1909–1988) dated 20 December 1937 13 reads: “[Guy] has had a bad time and I am quite sure he will never write another line on cephalopods. During his sane intervals he lives with his brother, but he unfortunately has repeated relapses when he returns to a mental hospital. It has been a very sad affair, originating with shell shock during the war and brought on again by domestic trouble.” Except for being elected an Honorary Member of the Malacological Society of London on 12 February 1937 (Anonymous, 1937b), years would pass before Guy’s name reappeared in print, sadly in the form of three brief obituary notices (Hindle, 1945, 1946; Smith, 1945). Adam (1946) delivered a far-more-fitting tribute to Guy’s life and contribution to the understanding of cephalopod taxonomy and phylogeny. No detailed biography of Guy has appeared since.

Inaccuracies in obituary notices In two near-identical obituary notices, Edward Hindle (1886–1973) speculated about Guy’s military past and his personal and academic interests (Hindle, 1945, 1946). Both accounts contained inaccuracies, with one (Hindle, 1945) even referring to Guy as “Dr G. C. Robson” in the title, and misspelling his middle name “Colborn.” Further errors or allegations therein included Guy having spent a year in Naples when it was five months, that “… in 1935 [Guy] had another nervous breakdown necessitating his resignation from the museum,” he was bombed during an air attack in WW1 and spent a year in hospital suffering from shell-shock before being invalided out of service, “… it is doubtful whether he [Guy] was entirely happy in his museum life …,” and that “he [Guy] never seemed to have fully recovered from his illness [referring to shell shock].” To someone unfamiliar with Guy’s research output and history, Hindle’s references to his “delicacy” (mentioned also by Smith (1945)), hospitalization, ongoing issues with shell shock, general unhappiness, the implication that he had multiple nervous breakdowns, and death after a long illness, suggest that Guy was and had been for some time both mentally and physically fragile. We present compelling evidence to the contrary.

Guy’s physical prowess (1903–1916) In September of 1903 Guy joined the Forest School Militia Volunteer Corps. Before leaving school in August 1906 he had achieved the rank of Second Lieutenant, and was adept with a rifle (Anonymous, 1906b). He also played cricket (Anonymous, 1904) and was a half-back in football, described as a “very energetic tackler,” and someone who excelled at running, hurdles, and the high jump (Anonymous, 1905, 1906b). By 1907 he had taken up soccer and cross-country running (Anonymous, 1907), and tennis by 1910 (Anonymous, 1910c: 221). He also played half-back for his old school as an “Old Forester” from 1910 to 1912 (Anonymous, 1910b, 1911, 1912). His pre-enlisting medical assessment 14 on 21 July 1916 categorised him as fitness level “B1,” meaning “free from serious organic diseases, able to stand service on lines of communication in France, or in garrisons in the tropics,” and “able to march 5 miles, see to shoot with glasses, and hear well” (Epsom & Ewell History Explorer, 2023). Were it not for a reference in his Bethlem medical file (18 December 1936) that at age 9.5 years he had rheumatic fever and “slight valve trouble,” but had no persistent problem with walking or talking, 15 an obscure reference to his health in 1906, that “we hope for greater things yet if Robson’s health holds good” (Anonymous, 1906a: 91), and a strained muscle prior to a running race (Anonymous, 1906b: 56), the many accounts of his school athleticism are inconsistent with any notion of his being physically fragile. His pre-enlistment medical evaluation also noted no major health conditions.

Guy delayed enlistment in the military for domestic reasons; he was the only family member left to care for his father, whose health and business had been seriously affected by the war (Shindler, 2018). Serving his country in other ways, in September 1914, with Dr Francis Bather (1863–1934), he was instrumental in establishing First Aid training for BMNH staff under the auspices of the local Red Cross branch. By May 1915 the volunteers, led by Guy, mobilised as a section of the 31st London Voluntary Aid Detachment of the Red Cross Society, acting as stretcher-bearers for the London Ambulance Column, attending the wounded arriving at London railway stations, and unloading men at hospitals. Guy’s section also watched for Zeppelins at night from the museum roof. In October 1915 his application to undertake Red Cross duties in Italy was denied because the museum would not apply to Treasury to fund his wages during his absence (Shindler, 2018). In April 1916 Guy joined the Officer Training Corps at Oxford University for two months, then applied for an Officer Commission in June, and voluntarily enlisted in the Royal Artillery on 7 June 1916. He was called up to serve shortly afterwards on 17 July, was first posted on 21 July to the Royal Field Artillery at the Officer Cadet Training School at Topsham in Exeter, and then on 18 August was posted to the Cadet school at Trowbridge and trained in siege artillery. Following his graduation on 11 October 1916 he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in the 2/1st Essex and Suffolk Royal Garrison Artillery manning the coastal defences at Shoeburyness. It is here where he probably first saw active service, or in January of 1917 when stationed at a siege battery. 16

Physical Health (1917–1918, 1936, 1944) Our first indication that Guy experienced any health-related issue during WW1 is his reference to “my never very legible writing is now rendered more illegible by a damaged thumb.” 17 This is followed by his 29 January 1917 admission to hospital with bronchitis, contracted after being stationed on an exposed battery and living in a draughty hut. 18 Several months later (June) he was admitted for “acute neurasthenia,” 19 and again on or before 8 July 1917 for problems with deep-seated varicose veins. 20 By 19 September he was admitted to a hospital for “shell-shocked officers” in Kensington, 21 where he remained until at least 9 December 1917 and was diagnosed with “peripheral neuritis” (14 November 1917). 22 He was discharged on 22 June 1918. Should a comment written to Sidney Harmer (1862–1950), 23 the then Keeper of Zoology, be anything to go by, “I have to confess that I do not find any reward in the Military Life adequate to compensate me for the deprivation of my Zoological work,” Guy did not particularly enjoy his military posting. “Neurasthenia” is now a seldom-used medical term for conditions characterised by exhaustion, a variety of pains, alterations in the senses, morbid fears, impairments in cognitive functioning, and alterations in mood (Abbey & Garfinkel, 1991). These symptoms were frequently associated with exposure to explosions from artillery shells during WW1, and the term neurasthenia became widely known by the equally ill-defined term “shell shock” (Alexander, 2010). The latter of Guy’s two diagnoses (that led to his discharge), peripheral neuritis, is more specifically characterised by damage to nerves outside of the brain and spinal cord (peripheral nerves), and is associated with weakness, numbness, and pain, usually in the hands and feet (Pai, 2023). While never explicitly stated in any medical report, this diagnosis may be related to a pre-existing condition with varicose veins, because on 8 July 1917 Guy wrote to William Calman (1871–1952) at the (then) BMNH to say that his “deep-seated varicose veins limited his chances of serving his country in a more active capacity,” and that he could hardly walk. 24 We have found no evidence that Guy was ever bombed or directly wounded during the war, nor any evidence that he was “shell shocked,” except that based on an imprecise diagnosis and his admission to a hospital that treated this condition. While in one letter he cryptically refers to doing something “useful and INTERESTING [his emphasis],” 25 neither could be construed as being bombed nor wounded. Accordingly, we have found no evidence to support Hindle’s allegations that Guy was bombed, or that he spent a year in hospital suffering from shell shock. Notably, the obituary notice of Smith (1945) makes no reference to Guy being shell shocked, but he does mention that Guy “for some time was laid up with injury to his feet.” Despite Guy’s claim that he could hardly walk, we are unaware of his experiencing any mobility-related issue after being discharged from hospital through to 1936; in 1936, when admitted to Bethlem, his “state of bodily health” was cited as “very good.” To the contrary, severe oedima in his legs and feet limited his mobility from at least 1944. 26

Two days before being discharged from the Officer’s hospital in Kensington, on 20 June 1918, Guy married Beryl Sinclair Nicholson (1899–1980). They first met (circumstances unknown) in 1912. 27 She was 19 when they married, and he 30, and they had two children—a son, Felix (1921–1999), and a daughter Ursula (1925–1996). Out of respect for the family’s privacy we do not delve into their personal lives from 1918 to 1932, but we must mention certain public-record details that are relevant to correcting inaccuracies in commentary regarding Guy (this being our objective). Additionally, while we have reconstructed a diary of Guy’s professional and public post-war engagements through to his 1936 departure from the BMNH, for brevity and relevance we do not dwell on those events from 1918–1930 either.

A marriage breakdown (1932–1933) As president of the Malacological Society of London, Guy typically presided over normal meetings throughout much of 1930 and 1931. However, in 1932 he is infrequently mentioned in Proceedings records, and meetings for the last three meetings of the year were chaired by Alfred Kennard (1870–1948). Then, on 23 January 1933, Guy petitioned for a divorce from Beryl, who had moved out of the family home and taken Ursula (7) and Felix (11) with her to live with a Thomas Chegwidden (1895–1986). 28 Later that year (14 October) the Richmond Herald (UK) (Anonymous, 1936a) ran a brief summary of court proceedings regarding Guy’s divorce application, divulging that Thomas had been a close friend of Guy and Beryl since “1926 or 1927,” that Guy had learned of their affair in August of 1932, and that Guy’s “efforts to induce Beryl to leave Thomas” had been unavailing. Guy’s absence from Malacological Society Presidential duties in the latter part of 1932 is perhaps consistent with his investing more time with his family during an understandably difficult time. In the week preceding Beryl’s departure, Guy was busy securing and preserving a giant squid that earlier that month had stranded on Southside Beach, Scarborough (Robson, 1933a). However, following his detailed report on this specimen, and several other brief publications (Robson, 1933b, c; Robson & Bidder, 1933) that comprised six pages in total, he all-but abandoned research and public engagement, excepting (of which we are aware) one 7 September 1933 event at which he spoke on “the limitations of adaptability in the animal kingdom” and the value of coordinated zoological surveys and centralised publication of results to the British Association for the Advancement of Science (Anonymous, 1933). On or around 20 December 1933 Guy voluntarily admitted himself to Woodside Hospital. 29

Institutionalisation (1933–1945) To our knowledge, no medical files remain for Guy between 1933 and 1936, and details of the time he spent in various institutions are limited (Table 2). On 20 April 1934 his doctor (Desmond Curran (1903–1985)) at Woodside Hospital had written to the BMNH to request additional leave for Guy, suggesting that he would make a full recovery from “a recent illness.” However, other than mentioning that Guy experienced anxiety, the nature of his illness was unspecified. 30 Although NHM archives through to 1936 include further correspondence between Guy and BMNH staff, or that otherwise involves him, nothing therein details Guy’s ailment(s). It is, however, apparent from these documents that Guy spent considerable time away from work, and that the museum went to great lengths to accommodate him and his absences, until continuance was no longer viable.

Table 2. Institutions and Hospitals (United Kingdom) at which Guy Coburn Robson stayed from 1933–1945 The first page of Guy’s admission sheet to Bethlem in December of 1936 31 specifies “no previous attacks” of depression, for his first attack to have been at age 45, for it to have persisted for “3 to 3.5 years,” and for his depression to have been “marked.” This suggests that Guy experienced no problems with depression prior to mid- or late 1932. When admitted, Guy was deemed neither suicidal nor homicidal, but within four days (18 December) he was placed under constant observation. Hereon, and through to his passing, evidence for his being “troubled” is incontrovertible, in that he resided within institutions and was obviously depressed, but other than his making repeated references to a sense of having failed his family and of personal inadequacy, he volunteered few specifics regarding the root cause(s) of his troubles. In December 1936, he revealed that a contract to complete a book had caused him grief. We deduce that he referred to Variation of Animals in Nature, a collaboration with Owain Richards (1901–1984), the publication of which was delayed until 1936. While contract documents dated 21 June 1928 between Guy, Owain, and Longmans, Green & Co Ltd 32 for delivery of this book (an anticipated 500-page tome) specified no delivery date nor made mention of an advance being paid, Guy and Owain did receive a lump-sum payment of £60 on 1 November 1933 for, we assume, submission of a draft manuscript. Because this book was printed in February 1936, Guy had obviously fulfilled his contract to the publisher and provided a final manuscript before volunteering himself to hospital. Therefore, while preparation of this book may have contributed to his anxiety, it is unlikely to have contributed to ongoing problems with depression. We were most fortunate to secure records of Guy’s stays at Bethlem from 1936 through to 1944, 33 and from Holloway Sanatorium from 1944 to his passing in 1945. 34 These files contain personal information that is mostly inappropriate to repeat. However, we present representative excerpts from these records where they assist us to correct errors in obituary notices, or explain what next happens to Guy—again, with the objective being to right an injustice that was done to his reputation. On 15 August 1944 when first admitted to Holloway Sanatorium, Guy’s brother Selby maintained that Guy had returned “back to normal life” in 1939, but that he had a “relapse” in 1942. 35 These dates are mostly corroborated by doctor’s entries in Guy’s Bethlem file, 36 where routine references to Guy’s general state of mental retardation and melancholy are interrupted by references to his making marked improvements. For example, file entries range from “his whole day is spent in bed in a room with the windows closed” (30 November 1937) to “he shows definite improvement and is most interesting to talk to” (30 December 1938), followed by an inexplicable year-long relapse from January of 1939–1940. In January 1940 his condition again improves, and an entry reads “at the moment he is better than I have ever seen him” (30 January 1940); in February an entry reads “relatively [sic.] to what he has been one could almost call him an extrovert now,” with notes (26 February 1940) also referring to him playing billiards with his “great friend,” another inpatient, the British stage and film actor Owen Roughwood (1876–1947). In May 1940 an entry reads “his retardation has disappeared.” This reprieve from depression persisted through to at least June, and quite possibly July 1942; he had even taken to venturing into London alone. Then, between 19 July and 10 August 1942, something triggered him, for on 10 August an entry reads that “Guy had relapsed for no apparent reason.” While his doctors suspected that they may have pushed him too hard, we note that this relapse roughly coincides with the release of Evolution: The Modern Synthesis by Julian Huxley (1887–1975), the first print of which (Huxley, 1942) appeared in the UK between June and August of 1942, the preface of which was written in March of that year, and drafts of which almost certainly circulated among Huxley’s peers prior to its release. Guy had only to read to page 31 of this tome to be humiliated by the savage critique of his 1936 The Variation of Animals in Nature, and 1928 The Species Problem, by his apparent friend (according to Erlingson, 2013), which Huxley referred to as an “undue, belittling of the role of selection in evolution, and an over-emphasis of the origin of species as the key problem in evolutionary biology.” Guy’s latest bout of depression, which persisted until at least August 1943, was followed by deteriorating physical health. 37 On 25 October 1943, he reported abdominal pain, and was jaundiced; a preliminary diagnosis of obstructive jaundice was made. Monthly entries through to April 1944 indicate that his health deteriorated progressively, but that there were continued delays in getting his condition medically assessed. Finally, on 8 June 1944, Guy was transferred to St John & Saint Elizabeth Hospital; days later, 14 June, he was discharged from Bethlem. 38 No St John & Saint Elizabeth Hospital medical records for Guy survive, but Holloway Sanatorium files indicate that he was treated there for jaundice from 8 June through to 15 August 1944. Eleven months on, at Holloway Sanatorium, Guy passed away of cardiac arrest, aggravated by biliary cirrhosis. 39 In the few days prior to his passing, which medical notes suggest was sudden and “while conversing with relatives,” his condition had deteriorated significantly. On 23 May 1945 the ashes of Guy Coburn Robson were sprinkled across the “crocus lawn” at Golders Crematorium, London. 40 His father, Thomas Pearson Robson (1857–1930) passed away of Bright’s disease (nephritis). 41 He was survived by his mother, Sarah Mary Broodbank (1861–1947), his brother Selby, and his two children, Felix and Ursula. Whether Guy died “suddenly” (sensu Anonymous, 1945; Smith, 1945) or after a “long illness” (sensu Hindle, 1945, 1946) all depends on whether you separate his protracted battle with depression from his relatively short bout of poor physical health.

Criticism of Guy’s research output (1977 onwards) This is where our abridged biography of Guy Coburn Robson’s life could have ended were it not for statements the preeminent teuthologist Gilbert Voss (1918–1989) made regarding him and his work, specifically referring to his two seminal monograph volumes (Robson 1929, 1932): “Robson attempted a monumental task, which was doomed to failure before it was started. The number of species was too large and contained too few critical reviews; too many of the species were known only from unique specimens, often female; and he was now suffering from the mental difficulties that shortly forced his retirement from the British Museum” (Voss, 1977: 54). Over a decade on, Voss continued: “Unfortunately the systematics of the deep-sea octopods, and in particular the cirrates, have been sadly neglected. Robson’s (1932) monographic study of the cirrates was the last attempt to make order out of the group. It did not succeed, partly because of Robson’s mental decline and partly because of the poor quality and quantity of available collections” (Voss, 1988a: 303). While collections of cephalopods at Guy’s disposal were unquestionably inferior to those available today, there is no evidence to suggest that Guy experienced any mental problem prior to December 1933 (it is possible for some issues developed in 1932 after learning of his wife’s infidelity). According to the preface in Robson’s second volume on octopuses, the text was completed by 2 November 1931. Ergo, Voss’s allegation that Guy was “now suffering from the mental difficulties …,” or that this affected the quality of his research output, is untenable. Most recently, Hodgson et al. (2021) also suggested that Guy stood down from editing the Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London at the end of 1927 “we suspect owing to health reasons,” but it is more probable that he relinquished this role to assume even greater responsibility as the society’s President. We posit that suspicion prior to and confirmation of Beryl’s suspected infidelity in August of 1932 (Anonymous, 1936a), the departure of his wife and children on 23 January 1933, 42 his deep sense of personal inadequacy and responsibility for the breakdown in his marriage, 43 and his obligation to complete The Variation of Animals in Nature, 44 triggered Guy’s troubles, rather than anything he experienced during WW1 (as intimated by Hindle). This is supported by Winckworth’s comment to Adam 45 that his current mental state was “brought on again by domestic trouble.” Should this be true then Guy’s mental decline in no way affected the quality of his research output when he was most productive. We report Guy’s mental state to have improved considerably between 1940 and at least July 1942, and for a relapse in August of 1942 to broadly coincide with Julian Huxley’s harsh critique of two of Guy’s books dealing with evolution. Guy’s last bout of depression was followed by a relatively rapid deterioration in his physical health, leading to his death at 57. Thiele (1935: 1689) commented “Robson began a monograph of cephalopods, of which so far the octopods have been completed (1929 and 1932).” Adam (1946) also concluded his eulogy to Guy with “In studying it [referring to the two volumes of his octopus memoir] one cannot but regret that Robson had not the opportunity to treat similarly of the Decapoda.” While our bibliography of Guy’s publications is more complete than that of Adam (1946), it is possible that other manuscripts exist. We have been unable to locate one titled “Remarks on melanism in land mollusca” that Guy presented on 9 May 1930 at an ordinary meeting of the Malacological Society of London. Guy also makes mention of his returning a completed manuscript for a new version of the Mollusca section of the BMNH Collector’s Handbook in correspondence with Sidney Harmer. 46, 47 Three (1902, 1904, 1906) of the four editions of the BMNH Collectors Handbook predate Guy’s employment at the museum, but in the fourth edition (BMNH, 1921) a chapter on “soft bodied and other invertebrate animals” solely attributed to Harmer might rightly have included Guy as a contributing author. Over and above his published output, further unpublished manuscripts do or did exist. NHM archives contain no draft manuscript on squids, so it appears that Guy had not embarked on any such project yet. However, one largely complete draft in the NHM archives written by Guy is titled “On the use and modification of the arm-web in the Octopoda.” A second largely complete draft on decapods of the “Arcturus” expedition was published posthumously (Robson, 1948). A further draft manuscript titled “Breathing tubes of Cyclophoridae” that was in Guy’s NHM files until at least 1975 cannot be located. Finally, we draw attention to a manuscript written by Guy at Bethlem on “dreams,” or more exactly, a “monograph on the mechanism of dreams from the organic point of view,” as it is referred to in his medical file. 48 On 22 October 1941 his doctor [initials DW, we assume Dr Duncan Whittaker (1906–1969)] wrote to say that this manuscript was “judicial and well expressed,” before continuing “He still sleeps badly and struggles hard against any reduction in his sedatives.” We can only imagine what Guy’s broken dreams involved, but we do hope that our contribution in some way helps him rest peacefully. We also hope that this contribution spells an end to any further questioning of the quality of his research. Finally, we note that according to Guy’s Bethlem medical file, 49 he “was happy” at work (18 August 1936), contrary to Hindle’s speculation otherwise. |

|

We extend our gratitude to David Luck, archivist for Bethlem Royal Hospital, Kent, and Julian Pooley, Surrey History Centre, Woking, UK, for their comments on a draft of this manuscript, authorisation to publish it, and information without which we would have been unable to piece together Guy’s life at the Bethlem Royal Hospital and Holloway Sanatorium, respectively. We also thank Michael Stansfield, Archivist and Records Manager, Oxford University, UK, for information regarding Guy at Oxford; Samantha Gautama and Susannah Coates, from Forest School, London, UK, who provided us with access to their archives, without which Guy’s early education would have remained a mystery; Kathryn Rooke, Laura Brown Emma Harrold, and Ceri Pollard, who assisted with the retrieval of information and documentation from the NHM archives, and Kevin Webb, for photographs of Robson’s microscope and specimen bottles, NHM, London, UK. We thank also Dr Yves Samyn, Royal Belgian Institute of Sciences, Belgium, who provided us with communications between Ronald Winckworth and William Adam, and between William Adam and Guy Robson, that enabled us to better understand certain events in Guy’s life; Helena Clarkson and Michele Drisse, The Museum of English Rural Life, University of Reading, Reading, UK, who provided us with access to contracts between the publisher, Guy Robson and Owain Richards regarding the Variation of Animals in Nature; and Julie Evans of Golders Green Crematorium Administration, UK, for information regarding Guy’s cremation and where his ashes were sprinkled. We further thank the Natural History Museum Archives for access to archived Department of Zoology, Departmental Correspondence (DF ZOO files) (by permission of the Trustees of The Natural History Museum); Dr CC Lu, Melbourne, Australia, for a critical and constructive review of an earlier manuscript draft; and Cyrielle Mallet (the wife of the first author) and Barbara Buge (Museum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France) for their translation of the English text of the Abstract of this manuscript into French. For their valued comments on and review of an earlier draft of this manuscript, we thank Drs Yves Samyn and Tristan Verhoeff (Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery Collections and Research facility, Rosny, Australia). Finally, we thank Angus Robson, Guy’s great grandson (a son of Felix), for his assistance in this contribution, and for his review and endorsement of this manuscript being submitted for publication. |

|

Abbey S. E. & Garfinkel P. E., 1991. Neurasthenia and chronic fatigue syndrome: the role of culture in the making of a diagnosis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148(12): 1638–1646. Adam W., 1946. A review of Robson’s work on the Cephalopoda. Proceedings of the Malacological Society, 27(3): 131–136. Alexander C., 2010. The shock of war. Smithsonian. September 2010. Anonymous, 1902. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1902: 63–93. Anonymous, 1903. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1903: 165–204. Anonymous, 1904. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1904: 277–319. Anonymous, 1905a. Forest School Magazine. Christmas Term 1905: 1–36. Anonymous, 1905b. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1905: 393–436. Anonymous, 1906a. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1906: 79–122. Anonymous, 1906b. Forest School Magazine. Easter Term 1906: 40–77. Anonymous, 1907. Forest School Magazine. Easter Term 1907: 164–199. Anonymous, 1910a. London Gazette, 2 December 1910. Anonymous, 1910b. Forest School Magazine. Christmas Term 1910: 1–40. Anonymous, 1910c. Forest School Magazine. Trinity Term 1910: 191–230. Anonymous, 1911. Forest School Magazine. Christmas Term 1911: 120–157. Anonymous, 1912. Forest School Magazine. Christmas Term 1912: 1–45. Anonymous, 1932. Hampstead News, p. 6, 6 October 1932. Anonymous, 1933. Dr G. C. Robson—The limitations of adaptability in the animal kingdom. British Association for the Advancement of Science, Report of the Annual Meeting, 1933: 487–488. Anonymous, 1936a. A husband’s petition. Richmond Herald, p. 3, 14 October 1936. Anonymous, 1936b. Retirement from Natural History Museum. Kensington News and West London Gazette, p. 3, 25 December 1936. Anonymous, 1937a. Untitled announcement of Robson’s retirement from the British Museum of Natural History. The Museums Journal, 36: 486–487. Anonymous, 1937b. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 1937, Annual General Meeting. Anonymous, 1945. Mr. G.C. Robson. Authority on Mollusca. The Times (London), May 21, 1945: 6. BMNH, 1921. Handbook of Instructions for Collectors. British Museum of Natural History. William Clowes and Sons. Pp. 222, pl. 1. CS, 1928. Challenger Society. Annual Report 1928, 2(i). CS, 1929. Challenger Society. Annual Report 1929, 2(ii). Epsom & Ewell History Explorer, 2023. Erlingson S. J., 2013. Institutions and innovation: experimental zoology and the creation of the British Journal of Experimental Biology and the Society for Experimental Biology. The British Journal for the History of Science, 46: 73–95. Hindle E., 1945. Dr G. C. Robson (obituary notice). Nature, 156: 75. Hindle E., 1946. Guy Coburn Robson, 1888–1945 (obituary notice). Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 26: 151–152. Hodgson A. N., Dussart G. & Raheem D. C., 2021. From print to on-line, a historical review of the Journal of the Malacological Society of London. The Malacologist, 76: 30–36. Huxley J., 1942. Evolution: The Modern Synthesis. George Allen & Unwin Ltd. London, 645 pp. Pai S. T., 2023. Peripheral neuropathy: 118–218 (chapter 14). In: Integrative Medicine, 5th Edition, Ed. Rakel D. and Minicheillo VJ. Elsevier. Robson G. C., 1911. The effect of Sacculina upon the fat metabolism of its host. Journal of Cell Science, s2-57(226): 267–278. Robson G. C., 1914. Cephalopods from the Monte Bello Islands. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1814: 677–680. Robson G. C., 1928. The Species Problem. An Introduction to the Study of Evolutionary Divergence in Natural Populations. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, London. 283 + viii pp. Robson G. C., 1929b. A monograph of the Recent Cephalopoda. Part 1. Octopodinae. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London. Pp. 236, 7 pls. Robson G. C., 1932. A monograph of the Recent Cephalopoda. Part 2. The Octopoda (excluding the Octopodinae). Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London. 359 pp., 6 pls. Robson G. C., 1933a. On Architeuthis clarkei, a new species of giant squid, with observations on the genus. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 103(3): 681–697. Robson G. C., 1933b. A Roman snail in the museum garden. Natural History Magazine of the British Museum, 4(27): 105–107. Robson G. C., 1933c. Importation of the dune snail into Western Australia. Nature, 132: 712. Robson G. C., 1948. The Cephalopoda Decapoda of the “Arcturus” Oceanographic Expedition. Zoologica, 33(3): 115–132, 18 figs. Robson G. C. & Bidder A., 1933. On the modification of the alimentary canal in abyssal cephalopods. Proceedings of the Linnean Society, 145(3): 125–126. Robson G. C. & Richards O. W., 1936. The Variation of Animals in Nature. Longmans, Green and Co., London, New York, Toronto, 425 pp., 2 pls. SEB, 1974. The Society of Experimental Biology. Origins and History. Thulprint Ltd, Lerwick, Shetland Islands, 36 pp. Shindler K., 2018. A Museum at War. Snapshots of Life at the Natural History Museum during World War One. Natural History Museum, London, UK, 232 pp. Southwood R., 1987. Owain Westmacott Richards, 31 December 1901–10 November 1984. Biographical Memoirs of the Royal Society, 33: 539–571. Smith G. F. H., 1945. Untitled obituary notice for ‘Mr Guy Coburn Robson.’ The Museums Journal 45: 101–102. Spier R., 2002. The history of the peer-review process. Trends in Biotechnology, 20: 357–358. Thiele J., 1935. Handbook of Systematic Malacology, Part 3. English translation by J. S. Bhatti, 1998. Smithsonian Institution Libraries, Washington. Voss G. L., 1977. Present status and new trends in cephalopod systematics. Symposium of the Zoological Society of London, 38: 49–60. Voss G. L., 1988. The biogeography of the deep-sea Octopoda. Malacologia, 29(1): 295–307. |

|

Supplementary Material 1 *Robson, G.C., 1911. The effect of Sacculina upon the fat metabolism of its host. Journal of Cell Science, 57(2): 267–278. DOI.org/10.1242/jcs.s2-57.226.267 Robson, G.C., 1912. On a case of presumed viviparity in Limicolaria. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 10: 32–33. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063463 — 1913. Helminthochiton aequivoca n.sp. Geological Magazine, 10: 302–304. DOI.org/10.1017/S0016756800126731 — 1913. Note on Glyptorhagada silveri (Angas). Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 10: 265. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063498 — 1913. On Aporemodon, a remarkable new pulmonate genus. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 11: 425–428. DOI.org/10.1080/00222931308692630 — 1913. On some remarkable shell monstrosities. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 10: 274–276. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063500 *Cummings B.F. & Robson G.C., 1914. Taxonomy and Evolution. The American Naturalist, 48 (570): 369–382. (Authors identified as ‘X’). DOI.org/10.1086/279413 Robson G.C., 1914. Cephalopods from the Monte Bello Islands. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1814: 677–680. — 1914. Molluscan rubber pests. Journal of Conchology, 14: 225. — 1914. On a collection of land and freshwater Gastropoda from Madagascar, with descriptions of new genera and new species. Journal of the Linnean Society, 32: 375–389, pl. 35. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1914.tb01462.x — 1914. Report of the Mollusca collected by the British Ornithologists’ Union Expedition and the Wollaston Expedition in Dutch New Guinea. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 20: 287–307. — 1914. The dentition of Veronicella nilotica, Cockerell. Appendix II: 266–268. In: Longstaff J., On a collection of non-marine Mollusca from the southern Sudan. Journal of the Linnean Society 32: 233–268, pl 17, 18. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1914.tb01456.x *— 1915. Note on “Katayama nosophora.” China Medical Journal, 29(3): 150–151. DOI.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.0366-6999.1915.03.102 — 1915. Note on Katayama nosophora. In: Leiper R.T., Atkinson E.L., Observations on the spread of Asiatic Schistosomiasis. British Medical Journal 1(2822): 203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25312519 — 1915. On the anatomy of Marinula tristanensis. Annals of the South African Museum, 15: 109–112. — 1915. On the extension of the range of the American slipper-limpet on the east coast of England. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 16: 496–499. DOI.org/10.1080/00222931508693743 — 1920. Observations on the succession of the gastropods Paludestrina ulvae and ventrosa in brackish water. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 6: 525–529. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932008632478 — 1920. On the anatomy of Paludestrina jenkinsi. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 5: 425–131. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932008632396 — 1920. Studies in British Hydrobiidae, Part I (abstract). Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 14: 1. — 1921. Is bisexuality in animals a function of motion? Nature, 108: 212. DOI.org/10.1038/108212a0 — 1921. On the anatomy and affinities of Hypsobia nosophora. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 8: 401–413. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932108632600 — 1921. On the Cephalopoda obtained by the Percy Sladen Trust Expedition to the Indian Ocean in 1905. Transactions of the Linnean Society, 17: 429–442, pl. 65–66. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1921.tb00473.x — 1921. On the molluscan genus Cochlitoma and its anatomy with remarks upon the variation of two closely-allied forms. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1921: 249–266. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1921.tb03264.x — 1921. The Mollusca as material for genetic research. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 14: 227–231. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063755 *— 1921. Sex-manifestation and motion in molluscs. Nature, 108: 403. DOI.org/10.1038/108403d0 — 1922. Notes on the respiratory mechanism of the Ampullariidae. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1922: 341–346. — 1922. On the anatomy and affinities of Paludestrina ventrosa, Montague. Quarterly Journal of Microscopical Science, 66: 159–185. DOI.org/10.1242/jcs.s2-66.261.159 — 1922. On the connexion between style-sac and intestine in Gastropoda and Lamellibranchia. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 15: 41–46. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063770 *— 1922. Rabaud, Étienne 1921. L’Hérédité. The Eugenics Review, 14(3): 196–197. PMCID: PMC2942460. — 1922. Self-fertilization in Mollusca. Nature, 109: 12. DOI.org/10.1038/109012b0 *Crew FAE, Dakin WJ, Harrison JH, Hogben LT, Huxley JS, Johnstone J, Marshall FHA, Robson GC, Saunders AMC, Thompson JM 1923. The British Journal of Experimental Biology. Science, 58: 102. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.58.1493.102.a *Crew FAE, Dakin WJ, Harrison JH, Hogben LT, Johnstone J, Marshall FHA, Robson GC, Saunders AMC, Thompson JM 1923. The British Journal of Experimental Biology. Nature, 112: 133–134. DOI.org/10.1038/112133b0 Robson GC 1923. A note on the species as a gene-complex. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 11: 111–115. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932308632829 — 1923. Guide to the Mollusca Exhibited in the Zoological Department, British Museum (Natural History). Oxford University Press, 55 pp. — 1923. Molluscan life on the south Dogger Bank. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 15: 174–178. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063802 Robson G.C. & Massy A.L., 1923. On a remarkable case of sex-dimorphism in the genus Sepia. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 12: 435–442. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932308632961 Robson G.C., 1923. On the external characters of Sinum planulatum (Récl.). Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 15: 268–269. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063816 — 1923. Parthenogenesis in the mollusc Paludestrina jenkinsi: part 1. British Journal of Experimental Biology, 1: 65–78. DOI.org/10.1242/jeb.1.1.65 Carleton H.M. & Robson G.C., 1924. On the histology and function of certain secondary sexual organs in the cuttlefish Doratosepion confusa. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 96: 259–271, pl. 3. DOI.org/10.1098/rspb.1924.0025 *Robson G.C., 1924. Interpretations of primitive American decorative art. Nature, 114: 381–382. DOI.org/10.1038/114381a0 — 1924. Mollusca. In: Hutchinson’s Animals of All Countries. London, Hutchinson & Co. Ltd. 4: 2034–2182. — 1924. On a new Doratopsis-stage of Cheiroteuthis from S.E. Africa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 13: 591–594. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932408633086 — 1924. On new species, &c. of Octopoda from South Africa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 9(13): 202–210. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932408633028 — 1924. On the Cephalopoda obtained in South African waters by Dr. J. D. F. Gilchrist in 1920–21. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1924: 589–686, pl. 1–2. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1924.tb01516.x — 1924. Preliminary report on the Cephalopoda (Decapoda) procured by the S.S. “Pickle.” Report of the Fisheries and Marine Biological Survey of the Union of South Africa, 3: 1–14. *— 1925. Book review. ‘The Biological Foundations of Society,’ by Dendy A. London: Constable and Co. 1924. Eugenics Review, 16(4): 285–286. Robson G.C. & Richards O.W., 1925. Investigations of the origin of insular races of land Mollusca in the Scilly Isles. Nature, 116: 641–642. DOI.org/10.1038/116641a0 Robson G.C., 1925. On a new species of Rossia from South Africa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 15: 450–454. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932508633233 — 1925. On a specimen of the rare squid Stenoteuthis caroli, stranded on the Yorkshire coast. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1925: 291–301, pl. 1. — 1925. On Mesonychoteuthis, a new genus of oegopsid Cephalopoda. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 9(16): 272–277. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932508633309 — 1925. On seriation and asymmetry in the cephalopod radula. Journal of the Linnean Society, 36: 99–108. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1925.tb01848.x — 1925. On the anatomy of an immature zonitoid land mollusc. Journal of the Federated Malay States Museums Kuala Lumpur, 8: 168–174, pl. 13–14. — 1925. The animal life of estuaries. The Journal of the Quekett Microscopical Club, 15: 161–168. — 1926. Cephalopoda from N.W. African waters and the Biscayan region. Bulletin de la Société des sciences naturelles du Maroc, 6: 158–195. — 1926. Editorial notes. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 17: 132–134. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063899 — 1926. Light-organs in littoral Cephalopoda. Nature, 118: 554–555. DOI.org/10.1038/118554a0 — 1926. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—1. Descriptions of two new species of Octopus from southern India and Ceylon. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 17: 159–167. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932608633384 — 1926. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—II. A.—On the habits and structure of Sepiola atlantica. B.—On a new species of Sepioteuthis from Tobago. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 18: 350–352. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932608633525 — 1926. On the hectocotylus of the Cephalopoda—a reconsideration. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 17: 117–122. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063896 — 1926. Parthenogenesis in the mollusc Paludestrina jenkinsi. Part II. British Journal of Experimental Biology, 3: 149–160. DOI.org/10.1242/jeb.3.2.149 — 1926. The Cephalopoda obtained by the S.S. Pickle. Supplementary Report. Report of the Fisheries and Marine Biological Survey of South Africa, 4(8): 1–6. — 1926. The deep-sea Octopoda. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 95: 1323–1356. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1925.tb07439.x *Richards O.W. & Robson G.C., 1926. The species problem and evolution (part I). Nature, 117: 345–347. DOI.org/10.1038/117345a0 *Richards O.W. & Robson G.C., 1926. The species problem and evolution (part II). Nature, 117: 382–384. DOI.org/10.1038/117382a0 Richards O.W. & Robson G.C., 1926. The land and freshwater Mollusca of the Scilly Isles and West Cornwall. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 92: 1101–1124. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1926.tb02237.x Robson G.C., 1927. Luminous squids and cuttlefish. Natural History Magazine of the British Museum, 1: 50–52. — 1927. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—III. On the anatomy and classification of the North Atlantic species of Bathypolypus and Benthoctopus. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 20: 249–263. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932708655596 — 1927. Report on the Mollusca (Cephalopoda) [of the Cambridge Expedition to the Suez Canal, 1924]. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 22: 321–329. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1927.tb00380.x — 1928. Cephalopodes des mers d’Indochine. Service Océanographique des Pêches de l'Indochine, 10: 53. — 1928. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—IV. On Octopus aegina, Gray; with remarks on the systematic value of the octopod web. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10(1): 641–646. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932808672833 — 1928. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—V. On the oviposition of Octopus rugosus. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 1(5): 646–647. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932808672834 — 1928. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—VI. On Grimpella, a new genus of Octopoda, with remarks on the classification of the Octopodidae. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 2(7): 108–114. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932808672862 — 1928. On the giant octopus of New Zealand. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1928: 257–264. *— 1928. The species problem. Geological Magazine, 65(9): 430. DOI:10.1017/S0016756800108295 — 1928. The Species Problem. An Introduction to the Study of Evolutionary Divergence in Natural Populations. Oliver & Boyd, Edinburgh, London, 283 pp. + viii pp. Clarke W.J. & Robson G.C., 1929. Notes on the stranding of giant squids on the north-east coast of England. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 18: 154–158. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063962 Joubin L. & Robson G.C., 1929. On a new species of Macrotritopus obtained by Dr. J. Schmidt’s ‘Dana’ Expedition, with remarks on the genus. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1929: 89–94. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07689.x Robson G.C., 1929. A giant squid from the North Sea. Natural History Magazine of the British Museum, 2: 6–8. — 1929. A monograph of the Recent Cephalopoda. Part 1. Octopodinae. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London, 236 pp., 7 pls. — 1929. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—VII. On Macrotritopus, Grimpe, with a description of a new species. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 3(15): 311–313. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932908672975 — 1929. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—VIII. The genera and subgenera of Octopodinae and Bathypolypodinae. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 3(18): 607–608. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932908673017 — 1929. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—IX. Remarks on Atlantic Octopoda &c. in the Zoölogisch Museum, Amsterdam. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 3(18): 609–618. DOI.org/10.1080/00222932908673018 — 1929. On a case of bilateral hectocotylization in Octopus rugosus. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1929: 95–9. — 1929. On the dispersal of the American slipper limpet in English waters (1915–29). Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 18: 272–275. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a063989 — 1929. On the rare abyssal octopod Melanoteuthis beebei (sp.n.): a contribution to the phylogeny of the Octopoda. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1929: 469–486. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1469-7998.1929.tb07702.x Aubertin D., Ellis A.E. & Robson G.C., 1930. The natural history and variation of the pointed snail, Cochlicella acuta (Mull). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1930: 1027–1055. Robson G.C., 1930. Cephalopoda. I. Octopoda. Discovery Reports, 2: 371–402, pl. 3–4. — 1930. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—10. On Octopus patatagonicus Lönnberg. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 5(26): 239–240. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933008673125 — 1930. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—11. On a new species of Benthoctopus from Patagonia with remarks on magellanic octopods. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 5(27): 330–334. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933008673141 — 1930. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—12. Observations on young octopods obtained by the ‘Dana’ Expedition. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 5: 366–370. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933008673147 — 1930. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—No. 13. The position and affinities of Palaeoctopus. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 6(34): 544–547. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933008673246 — 1930. On a specimen of Octopus vulgaris from Indian seas. Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 19: 117–118. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a064019 — 1930. Slug or horned viper? Nature, 125: 893. DOI.org/10.1038/125893d0 — 1930. Two remarkable cephalopods. Natural History Magazine of the British Museum, 2: 257–259. — 1931. Mollusca: 102–147. In: Pycraft W.P. (Ed), The Standard Natural History: from Amoeba to Man. Frederick Warne and Co., London. — 1931. Shells. Appendix M. In: Thomas B., A Camel Journey across the Rub’al Khali. The Geographical Journal, 78: 235. — 1931. The adaptability of the molluscan classes. (Presidential address.) Proceedings of the Malacological Society of London, 19: 259–266. DOI.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.mollus.a064050 — 1932. Shells. Appendix: 363–364. In: Thomas B., Arabia Felix: Across the Empty Quarter of Arabia. London, 435 pp. — 1932. A monograph of the Recent Cephalopoda. Part 2. The Octopoda (excluding the Octopodinae). Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History), London., 359 pp., 6 pls. — 1932. Exhibit of a remarkable larval cephalopod. Proceedings of the Linnean Society, 144: 102. — 1932. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—No. 14. On the shell-vestige of Cirroteuthis mülleri. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10: 179. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933208673487 — 1932. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—No. 15. On an interesting abnormality in Eledone cirrosa. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10: 180. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933208673487 — 1932. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—No. 16. On the variation, eggs, and ovipository habits of Floridan octopods. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10: 368–374. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933208673584 — 1932. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—No. 17. On the male of Benthoteuthis. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 10: 375–378. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933208673585 — 1932. On the phylogeny of the Octopoda. Archivio Zoologico Italiano, 16: 1118–1121. — 1932. Report on the Cephalopoda in the Raffles Museum. Bulletin of the Raffles Museum, 7: 21–33. — 1932. The closure of the mantle-cavity in the Cephalopoda. Jenaische Zeitschrift für Naturwissenschaft, 67: 14–18. — 1932. The morphology of the central nervous system of the Ctenoglossa (Cephalopoda). Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1932: 287–291. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1932.tb01077.x — 1933. A Roman snail in the Museum garden. Natural History Magazine of the British Museum, 4: 105–107. — 1933. Importation of the dune snail into Western Australia. Nature, 132: 712. DOI.org/10.1038/132712a0 *— 1933. Notes on the Cephalopoda.—XVIII. On a remarkable form of radula in the genus Graneledone. Annals and Magazine of Natural History, 12: 622–625. DOI.org/10.1080/00222933308673729 — 1933. On Architeuthis clarkei, a new species of giant squid, with observations on the genus. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 1933: 681–697. DOI.org/10.1111/j.1096-3642.1933.tb01614.x Robson G.C. & Bidder B., 1933. On the modification of the alimentary canal in abyssal cephalopods. Proceedings of the Linnean Society, 145: 125–126. Robson G.C., 1936. Mollusca: 48–64. In: Regan C.T., Natural History. Ward, Lock & Co., London. Robson G.C. & Richards O.W., 1936. The Variation of Animals in Nature. Longmans, Green and Co., London, New York, Toronto, 425 pp., 2 pls. *Robson GC 1948. The Cephalopoda Decapoda of the “Arcturus” Oceanographic Expedition. Zoologica, 33(3): 115–132, 18 figs. |

|

|

Steve O’Shea Phil Eyden Jonathan D. Ablett Amanda L. Reid |

| O’Shea S. et al., 2025. Guy Coburn Robson (1888–1945): from celebrated natural historian to obscurity. Colligo, 8(2). https://revue-colligo.fr/?id=107. |