Roger Casement’s Butterflies at the National Museum of Ireland – Natural History, Dublin, Ireland

Les papillons de Roger Casement au Musée national d’Irlande – Histoire naturelle, Dublin, Irlande

- Aidan O’Hanlon & Jorge M. González

|

Roger David Casement's multifaceted legacy transcends his well-documented roles in diplomacy and political activism, revealing significant contributions to the field of natural history. While notable for his exposure of the exploitation faced by indigenous communities in Africa and South America, Casement's work as a naturalist is equally compelling. As a British consul, he meticulously gathered cultural artifacts and samples of local flora and fauna, establishing relationships with leading contemporaneous scientists. Under the guise of naturalism, and utilizing the tools of an entomologist, he scrutinized the egregious actions of the Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company while meticulously documenting the region's biodiversity. Among his findings was a collection of butterflies from the Igaraparana forest in Putumayo, of which only six specimens seem to exist currently. This collection is presented and serves as a lasting testament to Casement's dual commitment as both a humanitarian advocate and a passionate naturalist, intertwining social justice with scientific pursuits. Keywords: Roger David Casement – history – Lepidoptera – Rhopalocera – inventory – National Museum of Ireland – Dublin L'héritage varié de Roger David Casement transcende ses rôles, bien documentés, qu’il a occupés dans la diplomatie et l'activisme politique, révélant des contributions significatives dans le domaine de l'histoire naturelle. S'il est surtout connu pour sa dénonciation de l'exploitation des communautés indigènes en Afrique et en Amérique du Sud, le travail de Casement en tant que naturaliste est tout aussi fascinant. En tant que consul britannique, il a méticuleusement rassemblé des artefacts culturels et des échantillons de la flore et de la faune locales, établissant des relations avec des scientifiques contemporains de premier plan. Sous le couvert du naturalisme et en utilisant les outils de l’entomologiste, il a suivi de près les exactions de la Peruvian Amazon Rubber Company tout en documentant méticuleusement la biodiversité de la région. Il a notamment rassemblé une collection de papillons de la forêt d'Igaraparaná, dans le Putumayo, dont il ne semble exister que six spécimens à l'heure actuelle. Cette collection est présentée et sert de testament durable au double engagement de Casement en tant qu'avocat humanitaire et naturaliste passionné, mêlant justice sociale et recherche scientifique. Mots clés : Roger David Casement – histoire – Lepidoptera – Rhopalocera – inventaire – Muséum national d'Irlande – Dublin El legado multifacético de Roger David Casement trasciende sus bien documentadas funciones en la diplomacia y el activismo político, revelando importantes contribuciones en el campo de la historia natural. Aunque es notable por haber sacado a la luz la explotación a la que fueron sometidas algunas comunidades indígenas de África y Sudamérica, la labor de Casement como naturalista es igualmente fascinante. Como cónsul británico, recopiló meticulosamente artefactos culturales y muestras de la flora y fauna locales, estableciendo relaciones con destacados científicos de la época. Bajo la apariencia del naturalismo y utilizando las herramientas de un entomólogo, examinó las atroces acciones de la Compañía Peruana del Caucho Amazónico, al tiempo que documentaba meticulosamente la biodiversidad de la región. Entre sus hallazgos se encuentra una colección de mariposas obtenidas en el bosque de Igaraparaná, en Putumayo, de la que actualmente solo parecen existir seis ejemplares. Esta colección se presenta y sirve como testimonio del doble compromiso de Casement como defensor humanitario y naturalista apasionado, entrelazando la justicia social con la búsqueda científica. Keywords: Roger David Casement – historia – Lepidoptera – Rhopalocera – inventario – Museo Nacional de Irlanda – Dublín |

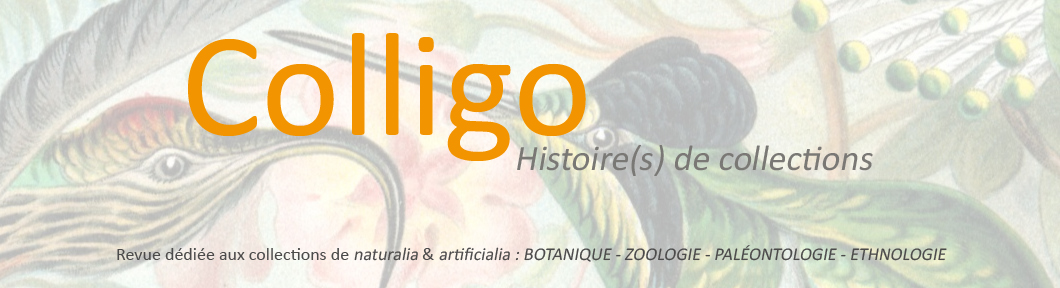

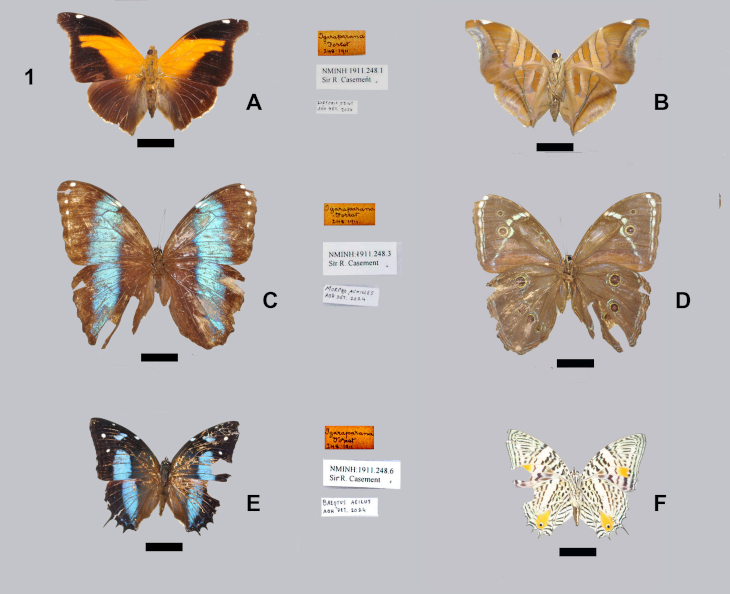

Butterfly specimens donated by Roger Casement to the entomological collection of the NMI-NH

Historis odius dious Lamas, 1995

Morpho menelaus occidentalis C. Felder & R. Felder, 1862

Morpho helenor theodorus Fruhstorfer, 1907

|

Although he is best remembered as a humanitarian and revolutionary nationalist, Roger Casement was also an amateur naturalist who made small but important contributions to Irish natural history collections. Among the many ethnographic and natural history specimens he donated to various Irish institutions, a selection of stunning Nymphalidae can still be found in the entomological collection of the National Museum of Ireland. Despite the observable damage to the specimens (see plates 1 & 2), their coloration, intricate patterns, and aesthetic appeal continue to engage and attract both enthusiasts and researchers who examine and analyze them. While his butterfly collection may lack significant scientific value, it serves as a powerful and unique lens through which we can explore and understand the complex legacies of imperialism, exploration, scientific discovery, extractive capitalism, decolonization, cultural nationalism, and humanitarian activism all at once. |

|

We extend our heartfelt gratitude to Gerardo Lamas (Museo de Historia Natural at Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Lima, Peru) and Andrew Neild (Research Associate, McGuire Center for Lepidoptera & Biodiversity). Gerardo verified the butterfly identities and shared valuable insights about the region where the butterflies were collected. Andrew was very kind in sharing information and references that helped us improve the original manuscript. |

|

Álvarez-Sierra J. R. & Álvarez-Corral J. R., 1984. Mariposas diurnas de Venezuela. Introducción a su conocimiento. Caracas: Editorial Arte, 200 pp. Barcant M., 1970. Butterflies of Trinidad and Tobago. London: Collins, 314 pp. Beccaloni G.W., Viloria Á.L., Hall S.K. & Robinson G.S. 2008. Catalogue of the hostplants of the Neotropical butterflies. Catálogo de las plantas huésped de las mariposas neotropicales. The Natural History Museum. Monografías Tercer Milenio, vol. 8, S.E.A., Zaragoza, 536 pp. Blandin P., 2007a. The systematics of the genus Morpho, Fabricius, 1807 (Lepidoptera Nymphalidae, Morphinae). Canterbury: Hillside Books, 277 pp. Blandin P., 2007b. The genus Morpho. Lepidoptera Nymphalidae. Part 3. Addenda to Part 1 and Part 2 & The Sub-Genera Pessonia, Grasseia and Morpho. Canterbury: Hillside Books, xi + 99-237, figs. 11–455. Blandin P. & Purser B.H., 2013. Evolution and diversification of Neotropical butterflies: Insights from the biogeography and phylogeny of the genus Morpho Fabricius, 1807 (Nymphalidae: Morphinae), with a review of the geodynamics of South America. Tropical Lepidoptera Research, 23(2): 62-85, 12 figs. Blandin P., Johnson P., García M. & Neild, A. 2020. Morpho menelaus (Linnaeus, 1758), in north-eastern Venezuela: description of a new subspecies. Tropical Lepidoptera Research, 30(2): 58-64, 9 figs. Casement R., 1997. The Amazon Journal (Edited by Mitchel A.). London: Anaconda Editions, 534 pp. Centro Amazónico de Antropología y Aplicación Práctica (CAAAP), 2012. Libro azul británico: informes de Roger Casement y otras cartas sobre las atrocidades en el Putumayo, IWGIA. Retrieved 23 June 2025, from https://biblioteca.corteidh.or.cr/adjunto/37162 Constantino L. M., 1997. Natural history, immature stages and hostplants of Morpho amathonte from western Colombia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Morphinae). Tropical Lepidoptera, 8(2): 75-80. Constantino L. M., 1998. Butterfly life history studies, diversity, ranching and conservation in the Chocó rain forests of Western Colombia (Insecta: Lepidoptera). SHILAP Revista de Lepidopterología, 26(101): 19-39. D’Abrera B., 1984. Butterflies of South America. London: Hill House, 256 pp. DeVries P.J., 1987. The Butterflies of Costa Rica and their natural history. Papilionidae, Pieridae, Nymphalidae. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 327 pp. Enrico P. & Pinchon R., 1969. Première partie. Les Rhopalocères ou papillons de jour des Petites Antilles : 29-144. In: Pinchon R. & Enrico P., Faune des Antilles Françaises. Les Papillons. Fort-de-France, Authors, 260 pp. Gernaat H.B.P.E., Van Den Heuvel J. & Van Andel H.T., 2016. A New Foodplant for Historis odius dious Lamas, 1995 (Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae) with Some Notes on the Life History in Suriname. Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society, 70(2): 159-163. Hart, W. A., 2017. African Art in the National Museum of Ireland. African Arts, 28(2): 34-97, 90-91. Hochschild A., 1999. King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. London: Houghton Mifflin, 366 pp. Inglis B., 1973. Roger Casement. London: Hodder and Stoughton Ltd., 462 pp. Janzen D. H. & Hallwachs W. 2009. Dynamic database for an inventory of the macrocaterpillar fauna, and its food plants and parasitoids, of Area de Conservacion Guanacaste (ACG), northwestern Costa Rica (nn-SRNP-nnnnn voucher codes). http://janzen.sas.upenn.edu. Lalonde M.M.L. 2021. Phylogenetic analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of the graphic beauty butterfly Baeotus beotus (Doubleday 1849) (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae: Coeini). Mitochondrial DNA (B) 6(4): 1516-1518, 1 fig. Le Moult E. & Réal P. 1962. Les Morpho d'Arnerique du Sud et Centrale. Published by the authors, Paris. xiv + 296 pp., 116 plates. Lamas G. (Ed.), 2004. Checklist: Part 4A. Hesperioidea - Papilionoidea. In: Heppner J. B. (Ed.), Atlas of Neotropical Lepidoptera. Volume 5A. Gainesville, Association for Tropical Lepidoptera; Scientific Publishers, 439 pp. Mitchell A., 2023. The Putumayo Atrocities. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Retrieved 23 June 2025, from https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/ view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-1111 Murillo-Hiller L.R., 2025. Butterflies and Moths of Costa Rica. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 316 pp. Neild A., 1996. The Butterflies of Venezuela. Part 2: Nymphalidae II (Acraeinae, Lybytheinae, Nymphalinae, Ithomiinae, Morphinae). A comprehensive guide to the identification of adult Nymphalidae, Papilionidae, and Pieridae. London: Meridian Publications, 276 pp. O’Hanlon A. & Mitchell A., (manuscript submitted for review). A Naturalist on the Margins: Roger Casement’s Natural History Collection and the Ambivalences of Colonial Knowledge Production. Archives of Natural History. Ó Síocháin S., 2008. Roger Casement: Imperialist, Rebel, Revolutionary. Lilliput Press, Dublin, 656 pp. Renoux H., 2011. The proving of Morpho menelaus occidentalis. Homeopathic links, 24(1): 45-47. Riley N.D., 1919. Some new Rhopalocera from Brazil collected by E. H. W. Wickham, Esq. Entomologist, 52: 181-186, 200-202. Scannell J.P. & Snoddy O., 1968. Roger Casement's contribution to the ethnographical and economic botany collections in the National Museum of Ireland. Éire-Ireland, 3: 46-54. Scott J.A. 1986. Distribution of Caribbean butterflies. Papilio (New Series), 3: 1-26, 2 tabs. van den Berghe E., Hernández Baz F., Pérez Vasquez M.E., & Orozco A., 2016. Baeotus beotus (Doubleday, 1849) (Lepidoptera: Charaxinae) nuevo para la Fauna de Nicaragua. Revista Nicaraguense de Entomologia, 102: 3–9. Vásquez Bardales J., Zárate Gómez R., Huiñapi Canaquiri P., Pinedo Jiménez J., Ramírez Hernández J.J., Lamas G. & Vela García P., 2017. Plantas alimenticias de 19 especies de mariposas diurnas (Lepidoptera) en Loreto, Perú / Food Plants of 19 butterfly species (Lepidoptera) from Loreto, Peru. Revista peruana de biología, 24(1): 35-42. Wetherbee D. K., 1991. Seventh contribution on larvae and/or larval host-plants of Hispaniolan butterflies (Rhopalocera), and nocturnal activity of adult Hypanartia paulla (Fabricius) (Nymphalidae). Shelburne, Author, 13 pp. Wylie, L., 2010. Rare models: Roger Casement, the Amazon, and the ethnographic picturesque. Irish Studies Review, 18(3): 315-330. |

|

Aidan O’Hanlon Jorge M. González |

| O’Hanlon A. & González Jorge M., 2025. Roger Casement’s Butterflies at the National Museum of Ireland – Natural History, Dublin, Ireland. Colligo, 8(2). https://revue-colligo.fr/?id=106. |