A fortunate man – The life and letter collection of Arthur Blok

Un homme fortuné – La vie et les lettres d’Arthur Blok

- Harriet Wood & Brian Goodwin

|

An archive containing 126 documents, compiled by Arthur Blok (1882-1974), was acquired by Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales, Cardiff, UK in 2019. It was donated by the family of the British shell collector, Edward Bishop (1936-2018). The process of conservation, digitisation, documentation and transcription of the archive is described, followed by an analysis of the archive in terms of the document types, make-up of the senders and receivers, temporal spread, geographical range and the languages the documents are written in. A 'cast of characters' is presented in Appendix 1, listing the senders, letter dates and recipients, in addition to some significant conchologists mentioned in the letters. Blok’s life and character are explored, and a chronological biographical summary of Arthur Blok’s life is presented, alongside his short bibliography, in Appendix 2; the relationship of Blok and Bishop is also discussed. Blok's passion for collecting letters is evidenced from 1934, with other instances also highlighted. The donation to Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales is put into context of other known Blok archives, notably a larger collection containing 470 letters residing in the Library and Archives, Natural History Museum, London, UK and a list of the correspondents it contains is presented in Appendix 3. The contents of the Cardiff Blok archive and its networks are then reviewed, with a particular focus on connections to Cardiff, the WW2 years and taxonomic debate. A notable relationship, between Lieut.-Col. Alfred James Peile (1868-1948) and Arthur Haycock (1863-1934) is further revealed, forming a short biography of the little-known Bermudian shell collector, Haycock. Keywords: Arthur Blok – Edward Bishop – archive – correspondence – history of conchology – social network – Alfred James Peile – Arthur Haycock – National Museum Wales Un fonds d’archives contenant 126 documents rassemblés par Arthur Blok (1882-1974) a été acquis par l’Amgueddfa Cymru – Museum Wales, à Cardiff, au Royaume-Uni, en 2019. Il a été donné par la famille du collectionneur britannique de coquillages Edward Bishop (1936-2018). Le processus de conservation, de numérisation, de documentation et de transcription de ce fonds est décrit, suivi d’une analyse des documents selon leur typologie, l’identité des expéditeurs et destinataires, la répartition chronologique et géographique, ainsi que les langues utilisées. Une liste des personnes est présentée en annexe 1, répertoriant les expéditeurs, les dates et les destinataires des lettres, ainsi que certains conchyliologues notables mentionnés dans la correspondance. La vie et la personnalité de Blok sont explorées, et un résumé biographique chronologique de la vie d’Arthur Blok est présenté, accompagné d’une courte bibliographie en annexe 2 ; la relation entre Blok et Bishop y est également abordée. La passion de Blok pour la collecte de lettres est attestée dès 1934, d'autres exemples sont également mis en lumière. La donation à l'Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales est replacée dans le contexte d'autres archives de Blok connues, notamment une collection plus importante de 470 lettres conservée à la Library and Archives du Natural History Museum de Londres, dont la liste des correspondants est présentée en annexe 3. Le contenu du fonds Blok de Cardiff et ses réseaux sont ensuite examinés, avec une attention particulière portée aux liens avec Cardiff, la période de la Seconde Guerre mondiale et aux débats taxinomiques. Une relation notable entre le lieutenant-colonel Alfred James Peile (1868-1948) et Arthur Haycock (1863-1934) est également révélée, donnant lieu à une courte biographie du peu connu collectionneur de coquillages bermudien, Haycock. Mots clés : Arthur Blok – Edward Bishop – archives – correspondance – histoire de la conchyliologie – réseau de sociabilité – Alfred James Peile – Arthur Haycock – National Museum Wales |

Materials & Methods: Conservation, documentation and transcription

Blok and Bishop – mentor and friend

Taxonomists over time – Peile and Haycock

Appendix 1: Cast of Characters and associated references

Appendix 2: Chronology of Blok’s life and bibliography

Appendix 3: Table of correspondents in the NHMUK Blok archive

|

Letter archives associated with natural history collections are gateways into the lives and relationships of collectors and taxonomists, offering a glimpse into discussions around identifications, collecting trips and the history and provenance of the specimens themselves. They form a supporting role in enhancing the interpretation of collections and type specimens (Wood & Gallichan, 2008; Breure, 2011 & 2013; Breure & Ablett, 2011, 2012, 2014, 2015), acting as handwriting identification aids, whilst feeding into the broader understanding of actor-networks in the field (van der Bijl et al., 2010; Breure, 2015; Breure et al., 2018; Breure et al., 2022).

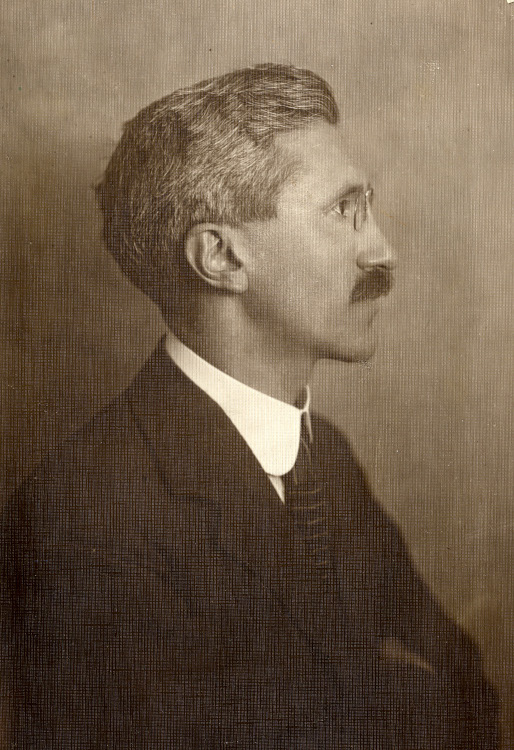

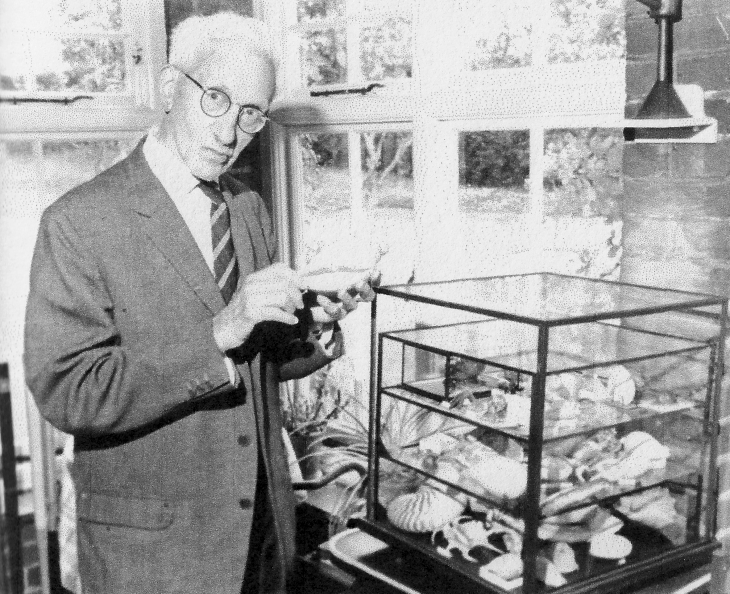

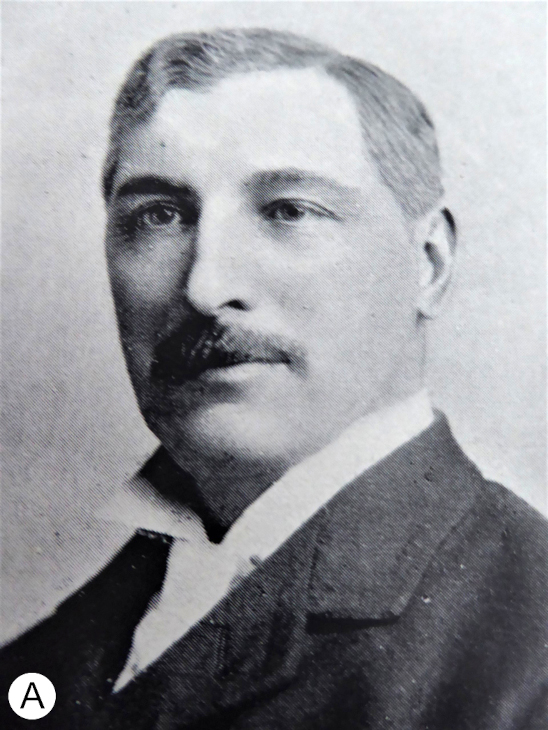

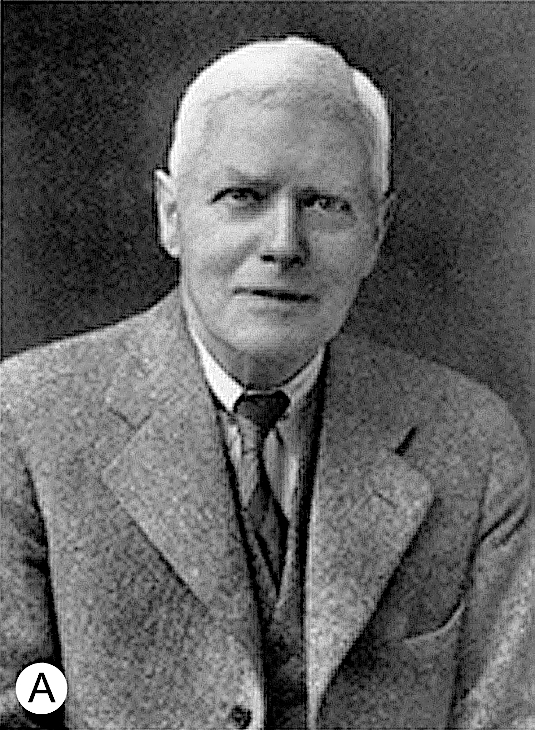

In 2018, a small archive of 126 letters, compiled by Arthur Blok (1882-1974) (Fig. 1), came to light during a review of Edward Bishop’s (1936-2018) mollusc collection at his home in Woodingdean, near Brighton, East Sussex, UK (Willing, 2019). The visit was hosted by Edward’s wife, Anne Bishop, and the review was undertaken by curators from Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales (Ben Rowson and Harriet Wood); both the Bishop collection and Blok archive were acquired by Amgueddfa Cymru-Museum Wales the following year. The Blok archive has since been scanned, rehoused, documented and transcribed by the authors for accessibility, interpretation and future online access through the Mollusca Types in Britain and Ireland website, a project funded by the John Ellerman Foundation and available at https://gbmolluscatypes.ac.uk (Ablett et al. accessed: 29 May 2025). This will be part of a new strand to the website, forming a hub for information on malacological archives in Britain and Ireland, which is due to be launched in 2025. Through this work a ‘cast of characters’ was formed and is presented in Appendix 1, illustrating the full list of senders, including a short biographical summary, the dates of all the documents (where known) and the conchologists to whom the letters were sent. In addition, some notable conchologists mentioned in the letters (mainly receivers) are also listed. As this is a collection of letters, rather than correspondence to a specific individual, a network analysis in relation to Blok is not undertaken in this paper. We consider the provenance of this archive, taking a look at Arthur Blok, his life (Appendix 2) and his friendship with Edward Bishop, to understand how it came to be in Bishop’s hands and where it sits in the bigger picture of Blok’s letter collecting. Undertaking this research revealed another, larger, Blok archive containing 470 letters, which was passed on to S. Peter Dance and then donated to the Library and Archives, British Museum (Natural History), London, UK in 1975, after being further augmented by Dance. The list of correspondents in this second augmented archive is presented in Appendix 3 and a comparison of the senders in both archives is made. With the archive spanning 1883 to 1958 we selected themes of particular interest and relevance to research further. The repeated occurrence of conchologists who had ties with Cardiff became apparent and has been explored, including any relationships with Blok, with a particular look at John R. le B. Tomlin, James Cosmo Melvill, William Evans Hoyle, J. Davy Dean and S. Peter Dance. Temporally, the letter occurrence peaks between the 1920s-1940s, therefore it is no surprise that WW2 is mentioned prominently and the stories and context around this have been reviewed. When assessing the archive, it became apparent that Peile was the recipient of a large portion of the letters (c. 40%), most likely given directly to Blok for his growing collection. Blok and Peile were indeed good friends and in 1945 Arthur Blok received his entire collection of Clausiliidae and Pupillidae and bought a huge collection of radulae from him (Mienis, 1975). Peile was known for his passion for Bermudian shells, and this was found to be weaved through many of his letters. His correspondence from amateur conchologist and Bermudian resident, Arthur Haycock, is a highlight in the archive, where four letters from Haycock can be found. It transpired when researching Haycock that little had been written about him and so the authors have expanded this section to compile a biography, including information on his collection in Bermuda. Institutional and Societal Abbreviations: ANSP: Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, USA

Materials & Methods: Conservation, documentation and transcription Bishop’s portion of Blok’s letter archive was discovered in November 2018 during a visit to Edward Bishop’s home to review his shell collection. It was in a desk drawer, in his shell collection room, and the letters were stored in an A4 sized padded Jiffy envelope labelled externally by Bishop, “handwritten letters from early conchologists – coll. by Mr A. Blok” (Fig. 2). Within the bag, the letters were bundled together, and many were attached together with metal paperclips showing signs of rust.

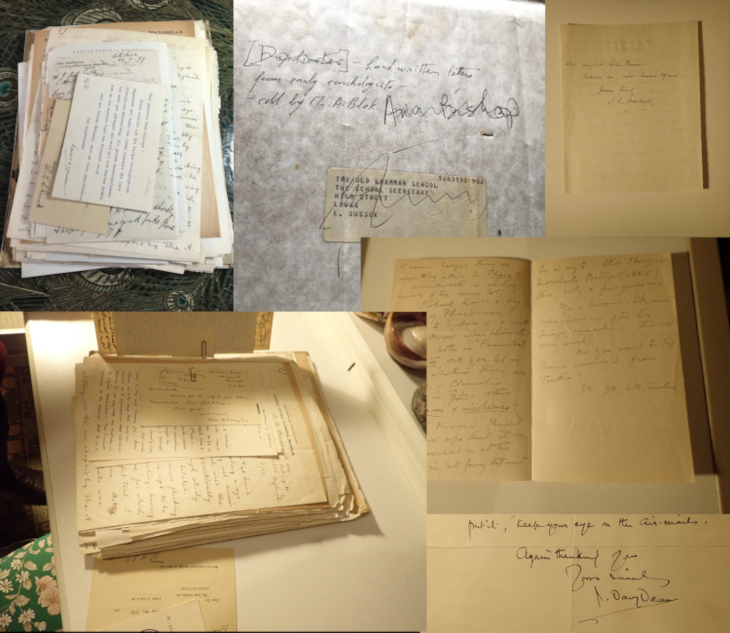

When the archive of 126 documents arrived at NMW in 2019, it was augmented into the malacological archive collection in the Natural Sciences department under accession NMW.Z.2019.005, and each document was given a unique registration number. The collection was rehoused, with each page stored in a Secol polyester pocket, with the accession/registration number printed onto Mellotex paper and taped to the outside using L-jar archival tape. The full collection was then stored in a single Timecare archive ring binder (Fig. 3). In July 2021, Harriet Wood was contacted by Brian Goodwin (Treasurer of the CSGBI, at the time), having heard about the acquisition of the Blok archive, and with an offer to undertake the letter transcription. His keen interest in malaco-history, and repertoire of related Mollusc World articles, was very complimentary to such a project and so a remote workflow between the authors began. Existing archive projects at NMW (namely the Tomlin archive project) meant that there was a pre-existing workflow for documentation of such material, and this was followed. In late-2021 and 2022, each document was scanned and saved as a high-resolution tiff at 300dpi, with copies saved as lower resolution jpgs. Each image had a unique image number, which was also attached to the polyester pocket containing the related document (Fig. 3). Images were shared with Brian Goodwin for transcription and documentation. The NMW Filemaker Pro malaco-archive database, originally created for the Tomlin archive, was used and allows images of the documents and the corresponding data to be viewed side-by-side. Alongside the transcription of the letters and other documents, information relating to each one was captured, primarily: Sender and receiver details (verbatim name, full name, address, country, gender), document type (letter, envelope, postcard, photograph, sales or collection list, note, drawing etc), folio and page number, content summary and accession details. By the end of 2023, most of the work had been completed and was ready for online publication on the Mollusca Types in Britain & Ireland platform; this new section to the website is still undergoing development by NMW staff and is due to be completed before the end of 2025. Throughout the transcription process a ‘cast of characters’ was created by the authors, which forms the backbone of the list presented in Appendix 1. All 126 letters are listed alphabetically by sender surname, including letter date, recipient and a brief biography of the sender. It is further enhanced with some of the notable conchologists and collectors mentioned in the letters, predominantly the receivers.

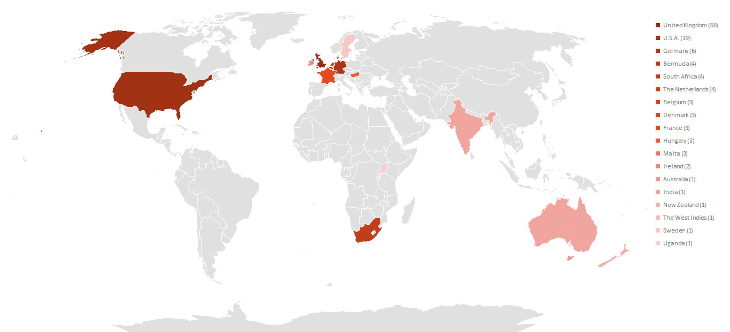

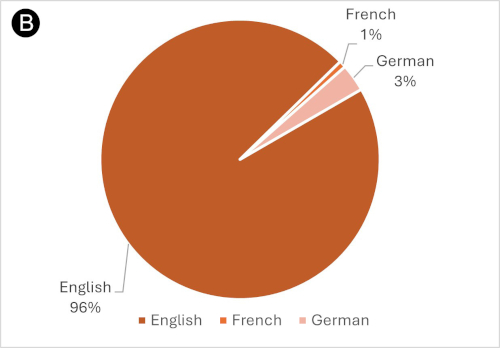

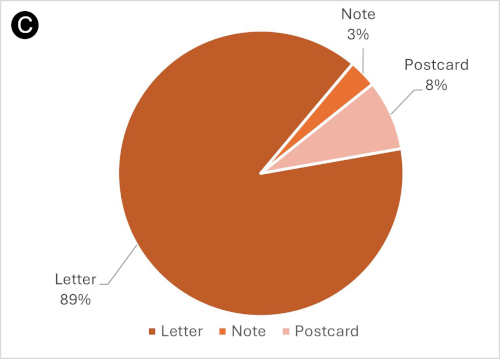

Media The media type within Bishop’s Blok collection is limited to just three types. The majority are letters, which make up 89% of the collection; in addition, there are 10 postcards (8%) and 4 notes (3%) (Fig. 5c). Seventy five percent of the documents are holographs (handwritten) and 25% are typed and signed. Surprisingly, there are no photographs or portraits at all, which are often found in similar archives such as Tomlin’s in NMW, Cardiff and Dautzenberg’s in RBINS, Brussels (Breure, 2015). There are also no cards, collections or sales lists, invoices, maps, or other media types. Geography and language Although it is clear which country most of the letters originated from (Fig. 4), it is not always apparent, without further research, whether the sender was a visitor, expat, or settler. There are only 4 documents where the senders’ country is not clear, either from the address, postmark or from information within the letter. The Steenstrup notes represent 3 of these and have been recorded as Denmark, his country of residence. The other is a letter from Hugh Watson, which has been recorded as the United Kingdom for the same reason. Nearly all correspondents used the English language (96%), with just two letters and two postcards in German, and one letter in French (Fig. 5b).

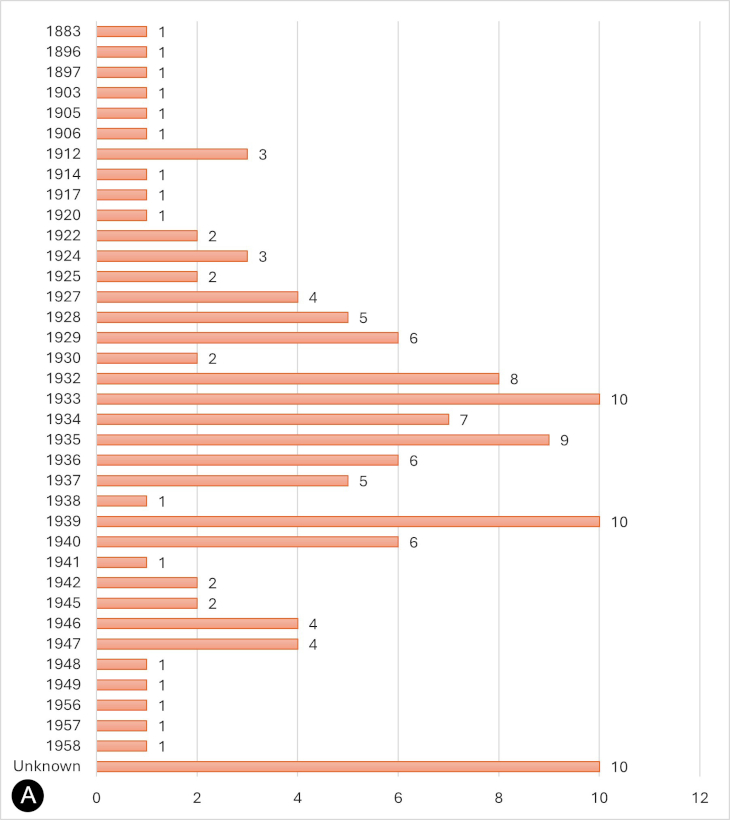

Timespan The letters cover a 75-year period, ranging from 1883 to 1958. The majority being from the 1920s to 1940s (87%) (Fig. 5a), covering the WW2 period.

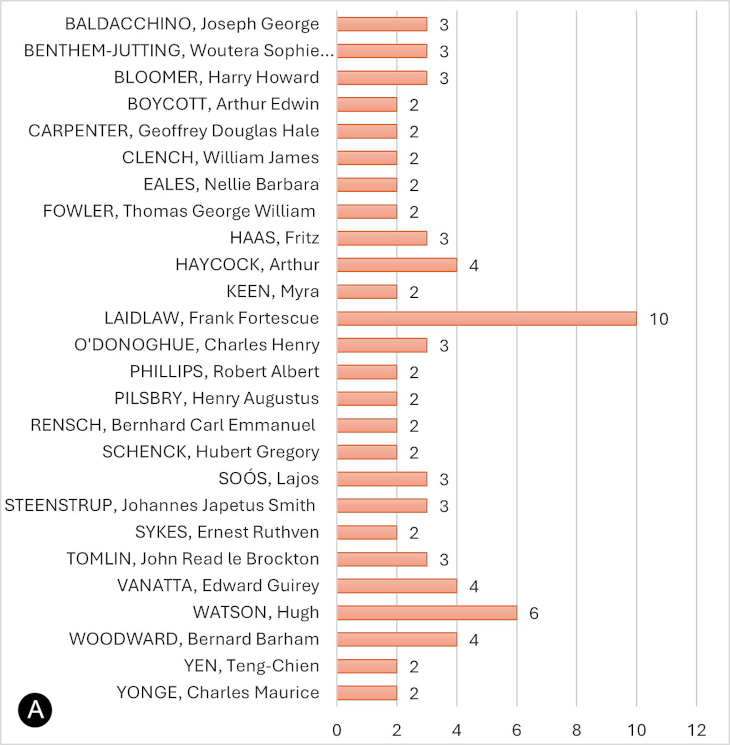

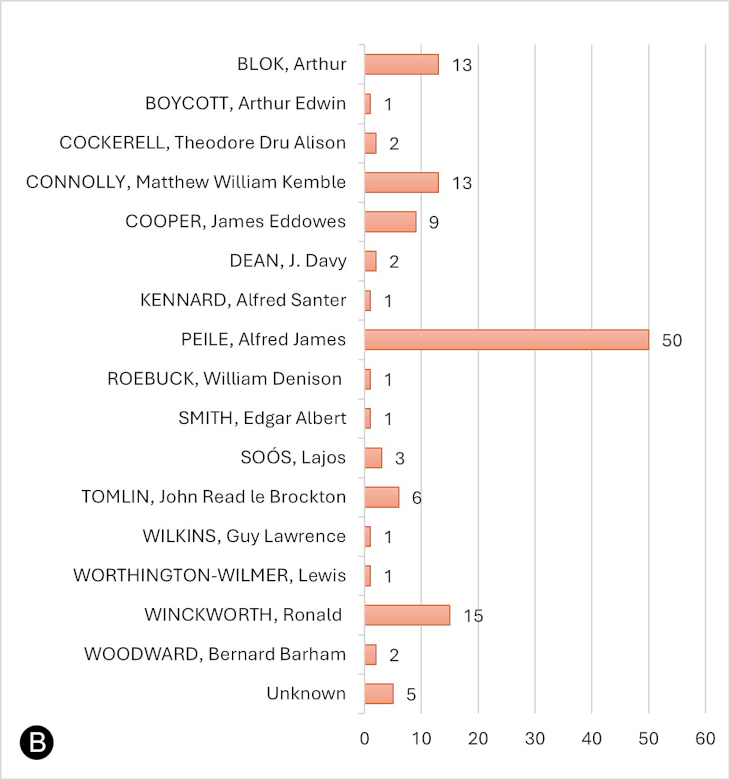

Receivers Unsurprisingly, many of Bishop’s letters seem to have been obtained from (and were addressed to) conchological friends who lived close to Blok in or near London, specifically Lieut.-Col. Alfred Peile (1868-1948), Major Matthew Connolly (1872-1947), Ronald Winckworth (1884-1950) and James Cooper (1864-1952). There are only 16 named recipients in the whole archive. Peile represents the largest portion of receivers with 49 letters, nearly 40% of the whole collection. This is followed by Winckworth (15 letters), Connolly (13 letters) and Cooper (9 letters), and collectively these four make up nearly three quarters of the recipients (Fig. 6b). There are also 11 letters (possibly 13) addressed to Blok himself.

Within the collection there are three manuscript notes written by Johannes Steenstrup (1813-1897), which understandably do not have a receiver, and five letters to unknown people; the latter simply refer to the receiver as “Dear Sir”. The content of two of the unknown letters do suggest they could have been to Blok, as they are letters from Ernest Sykes (1867-1954) discussing sending on a batch of Melvill’s reprints, and it is known from correspondence between Blok and John Wilfrid Jackson (1880-1978) in the archive at Buxton Museum & Art Gallery (BMAG), that Blok was attempting to obtain a full set, which is discussed in more detail further on. Two other letters to unknown recipients are annotated, and the writing may be that of Peile. It should also be noted that all the receivers are male. Nearly all the letters were sent to addresses in England (113), with just 3 to Hungary and 2 to the USA. All three letters to Hungary were addressed to Lajos Soós (1879-1972) (Fig. 7a), perhaps the country’s most eminent molluscan expert - many conchologists and malacologists are commemorated in species eponyms, but few can boast of having their country’s main molluscan journal named in their honour (Fig. 7b).

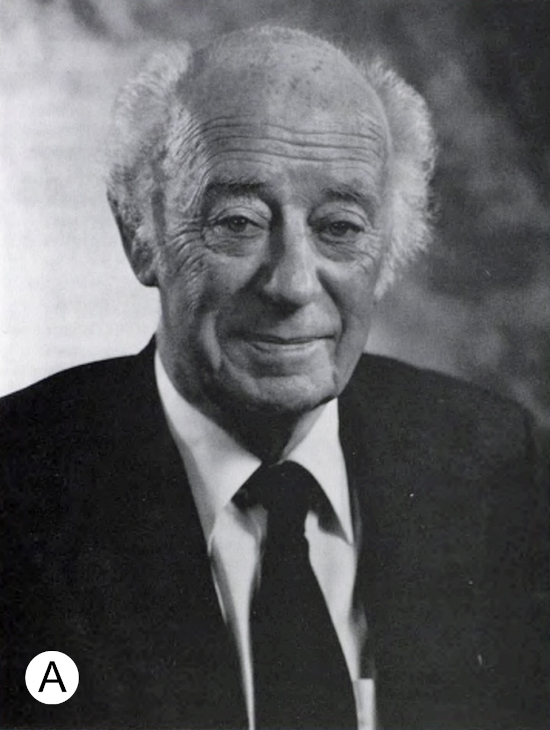

Senders The letter writers represent a much more diverse collection, with 74 different correspondents (Fig. 6a), from 18 different countries (Fig. 4), with more than a dozen different nationalities represented. Of the 74 correspondents, 48 are represented by a single letter and 13 by 2 letters, collectively making up nearly 50% of the whole collection and illustrating the ‘autograph’ nature of the archive, rather than it being a full history of correspondence. Only Frank Laidlaw (1876-1963) reaches 10 letters, with the next highest being 6 from Hugh Watson (1885-1959). Most writers were male, with 68 men represented by 116 documents. The female representation is much lower, with 6 female conchologists sending 10 letters. Before delving into the archive, it is important to know something about Arthur Blok (Fig. 1, 8) and his life. Judaism was enormously important to him, he was extremely proud of his heritage and a significant figure in his Jewish community, where he advocated for student welfare and education (Emanuel, 1974). He became a Zionist during WW1 (Mienis, 1975) and was involved in several major projects in Palestine (Emanuel, 1974). Through his marriage to Buena Sarah Pool (1881-1949) in 1907, he also became the brother-in-law and friend of Dr David de Sola Pool - Rabbi and world leader in Judaism (Emanuel, 1974).

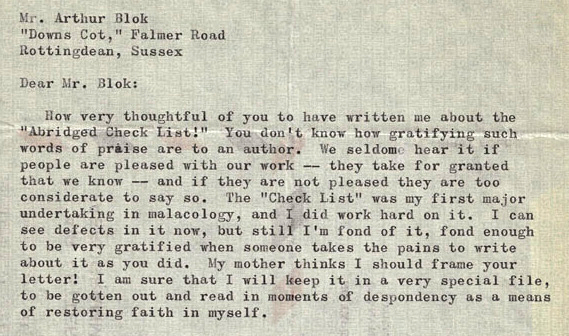

Blok’s career as an electrical engineer was book-ended by his involvement in two of the most significant areas of scientific development of the 20th century – wireless telegraphy and the atomic bomb. At the end of 1901, as a young electrical engineer (19 years old) acting as assistant to Sir John Ambrose Fleming, he took part in the first transatlantic relay of a long-range wireless telegraph communication from Poldhu (in Cornwall) to the Italian radio pioneer Guglielmo Marconi in Newfoundland. Blok, in fact, actually made some of the apparatus used in the transmission and noted in a radio interview that he also “had the mortification of seeing some of my apparatus go up in blue flames.” (Blok, 1973a). And then in 1903 he was part of a public demonstration of a long-range wireless telegraph transmission from Chelmsford to a gathering at the Royal Institution in London. Blok himself (1954) gave an account of the event (quoted in Hong, 2001) and there is an amusing side-story to proceedings, describing an early instance of ‘hacking’ (Marks, 2011). Blok not only worked with Fleming and Marconi, but also other eminent physicists including Sir Edward Appleton and Enrico Fermi. In an interview, he said of his career “I’ve been a fortunate man” (Blok, 1973b). Then, much later in life when Blok was Principal Examiner at the Patent Office, he played another vital supporting role during WW2. Great secrecy surrounded his involvement at the time, and what was originally a short-term deployment became a lengthy and important contribution. As Blok observed ....“I remained about five years out of the three or four weeks!” (Blok, 1973c). Blok’s involvement concerned resolving patent issues on the Manhattan Project, the research program to design an atomic bomb that Britain had initiated in 1941. Eventually the United States took over the lead but with scientists of both countries working together, a common policy regarding patent arrangements was necessary to protect both individual and national rights. This was easier said than done (Jones, 1985 – see pages 247-8). After a great deal of legal wrangling, shuttle diplomacy and many transatlantic crossings (Blok, 1973c; Goodwin, 2013; Goodwin, 2021), Blok and the Americans succeeded in putting together an agreement, without which the development of the atomic bomb would inevitably have been delayed, and the course of history changed. Blok was rewarded with an O.B.E. and shortly after, in early August 1945, the Americans detonated the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs. Alongside these career achievements, he built one of the world’s greatest shell collections (Emanuel, 1974; Mienis, 1975), which resides in HUJ, Israel, as desired by Blok during his life. Blok’s generous and kind nature is evident throughout all the articles written about him and from conversations with Anne Bishop, who knew him personally through her husband Edward. However, his character is perhaps best captured by Emanuel (1974), who summarises Blok beautifully: “… I refer to Blok as a wonderful human being, to his outstanding charm, his widespread knowledge and constant desire to improve it yet further, his sense of humour and fun and above all, his humility. Each and every person was important to him. As much time as he had for an old friend, he had no less for the younger generation whose new ideas were so different.” Pain (1976) highlights Blok’s innate ability to interest and inspire others in learning about conchology, which can also be seen through his complimented talks at CSGBI meetings (Wilkins, 1935, 1938). His kindness and generosity are illustrated in the responses to some of his letters in the archive. A 1956 letter from Myra Keen exemplifies this (Fig. 9): she is responding to a letter from Blok complimenting her on her recently published Supplement to An abridged check list and bibliography of West North American marine Mollusca (Keen, 1956). She is clearly touched as her response is effusive, even commenting that her mother thinks she should frame his letter!

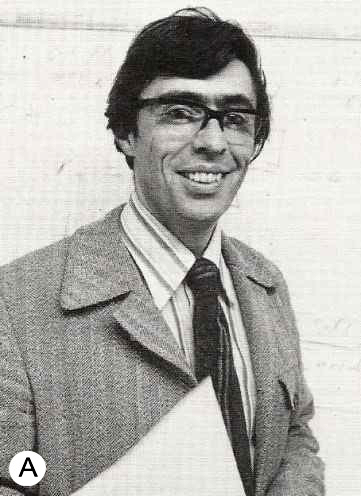

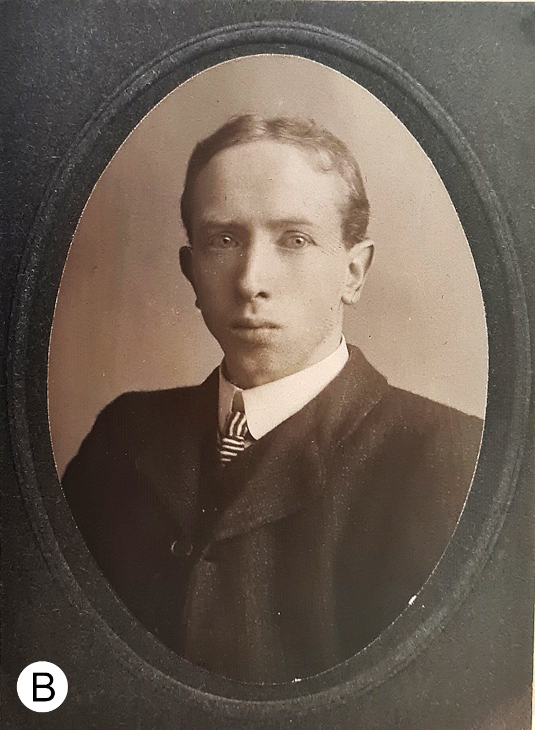

There is no doubt that Blok was a natural born collector, with an obsessive interest in order and neatness characterising everything he did (Pain, 1976). As a shell collector, Blok seems to have pursued a ‘full set’ approach – as many of a particular genus or family as he could get his hands on, illustrated by the presence of some 13,000 species in his collection (Blok, 1964; Emanuel, 1974; Mienis, 2012b). He also applied this to collecting reprints, or “separates” as he usually termed individual articles reprinted from journals. In a letter to John Wilfrid Jackson (25 March 1933, BMAG archive), he commented: “you know what it is with separates: one is always ready for more.”. As we shall explore, it seems that this also followed through to his letter collecting. Blok’s life has been well documented by Emanuel (1974), Mienis (1975, 2012b), Pain (1976) and Goodwin (2013, 2021), and additionally by Blok himself (1964). Mienis (1975, 2012b) also provides an excellent overview of the transfer of Blok’s collection from the UK to HUJ, including communications that took place and a detailed summary of the contents of the collection. These resources have been used to produce the chronological summary of Blok’s life outlined in Appendix 2. We have seen that Blok was both fastidious in his collecting and generous with his time and knowledge. It is also worth recording that he was both modest and self-deprecating, while his sense of humour has been referred to by Emanuel (1974). To round off this section we present some examples of his ready wit. When, in a radio interview (Blok, 1973b), it was suggested one of his hobbies was gardening, he replied, “No, gardening is more an occupational disease than a hobby. I do a little because I know it is good for my spare parts and good for the garden but what I’m really waiting for is the Brighton & Hove Weed Show. I shall get the Gold Cup, the Silver Medal, the Belt of Honour, the whole lot for my weeds!”. Questioned on a more serious point, as to whether he had foreseen that wireless transmission would advance so quickly, he swiftly riposted “My name is Arthur Blok, and not Elijah the Prophet!” (Blok, 1973a). Blok and Bishop – mentor and friend Arthur Blok was a true collector and curator at heart, with a wealth of knowledge that he was happy to share with anyone who was interested (Blok, 1964; Emanuel, 1974; Pain, 1976; Mienis, 2012b). It should not therefore be a surprise that he took a young Edward Oliver Bishop (1936-2018) (Fig. 10a) under his wing after semi-retiring to the coastal village of Rottingdean, East Sussex, UK in January 1948 (Pain, 1976). Bishop had been frequenting Rottingdean from a very young age and was an avid shell collector throughout his life; as a boy he often stayed at his aunt’s house in the village and is said to have collected his first shells from the local beach, at just two years old (A. Bishop pers. comm.). When Blok retired to Down’s Cottage, affectionately referred to as ‘Downscot’ (Fig. 8), he befriended Bishop’s aunt. Ed would have been twelve when Blok moved there, and Blok 65. Although we don’t know exactly when they first met, it was probably very shortly afterwards, through the commonality of Edward’s aunt and their shared interest in shells. In his archive material at NMW, Bishop refers to Blok as “My mentor over many years…I knew him since I was a small boy, on holiday” and Anne Bishop describes them as very good friends, with Edward respectfully referring to his mentor as “Mr Blok”, rather than Arthur.

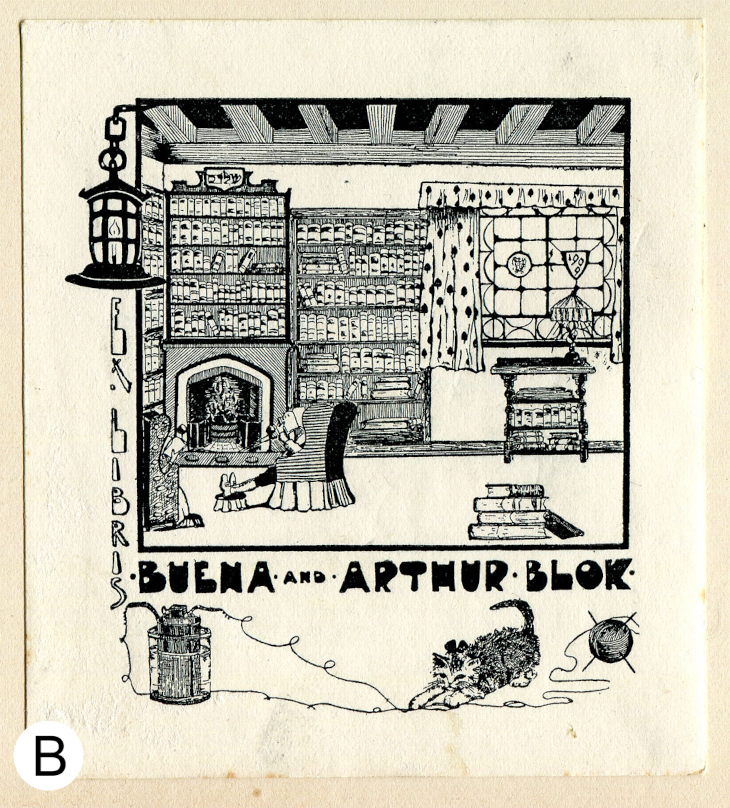

During the 1960s, when Bishop was in his 20s, he began to purchase duplicates from Blok “over a long period” at sixpence (6d) per species (Bishop archive, NMW). Blok stored specimens in his house and at a local convent (Anne Bishop pers. comm.; Bishop archive, NMW). Anne Bishop describes Blok as having a Victorian-style study with specimens organised in lovely dark wooden cabinets; according to Emanuel (1974) the cottage was beautifully panelled by Blok himself and there is clear pride and love of his home shown on the book plate he created for the library he shared with his wife, Buena (Fig. 10b). These are presumably some of the same cabinets pictured by Mienis (2012a) in the HUJ, described as “Victorian cupboards that house the Blok collection”. When Bishop visited Downs Cottage, Arthur would get out stacks of duplicates for him to go through and select those he wanted; on completion the trays were said to be “Bished!” and then put away (A. Bishop pers. comm.). In his notes, Bishop describes some material as being stored in Blok’s garage, whereas “Most of his coll[ection]. was stored in the main assembly room of St Mary’s Convent, a few hundred yards up the road”. So, it would appear that Blok had separated duplicate specimens that he wished to sell and share with others, keeping them at his home, whereas his main collection, destined for Jerusalem, was stored at the local convent. Blok was not only an avid collector of shells but was also interested in the associated conchological literature and ephemera – including, books, reprints, pamphlets and letters. When exactly his interest in letters arose it is not clear, but we know that he was already collecting such material by the mid-1930s. When Lajos Soós (1879-1972) (Fig. 7a), of the Hungarian National Museum, responded to Blok regarding corrections to his English language article on 29 November 1934 (NMW Blok archive), it is apparent that Blok had asked for a supply of letters from him: “You will find enclosed letters of several continental malacologists. I suppose you will find some of them useful.” The following month, in a letter from John Davy Dean (1876-1937) to Blok he discusses the swapping of stamps, as well as shells, but when signing off it is clear that Blok had also asked him to consider passing on any conchological letters (15 December 1934, NMW Blok archive): “I will certainly remember you with any letters of conchologists or books…” His following letter from Soós on 7 January 1935 (NMW Blok archive) further mentions the letters: “I am pleased very much that I could send you several letters of malacologists the manuscripts of whom were unknown to you.” On the 19 October the same year, Blok attended the 628th meeting of the CSGBI, which was held at the Royal Society, London (Anon, 1935). In addition to being elected as one of the two ‘Scrutineers’, he brought a diverse array of shells and shell-related items. Alongside some of Maynard’s Cerions, a colour and size series of Cypraea tigris, Victorian mother of pearl thread-winders and counters, and an engraved Nautilus collected in the 1850s, he presented several items relating to William Turton’s 1831 Land and freshwater shells publication. He had Canon Alfred Merle Norman’s (1831-1918) copy, with manuscript notes and addenda, but also two holograph letters. One was from Turton (1762-1835) himself, dated April 1828, to an unknown recipient, “acknowledging receipt of a parcel of shells and referring to diagnoses of others”; the second was written ten years later in May 1838 by John Edward Gray (1800-1875), writing to Joshua Alder (1792-1867) for information he wanted for his forthcoming revision of Turton’s book, which was published in 1840. Jumping forward ten years, Blok makes further mention of his holograph collection in 1946, when he writes to the recently retired Secretary of the CSGBI, John Wilfrid Jackson (CSGBI archive): "I have just had a chance of looking through a file of Mörch’s correspondence with the American conchologists between the ‘60s and ‘80s – most interesting. Letters from Lea, Stimson, G.W. Tryon Jr. and all the Yankee fathers, and I later hope to see the files of his letters from the European men of the same vintage. I shall try to acquire a few for addition to a colln. of conchological holographs which I have put together as a side line over some years.” It seems that the letters now at NMW, from Edward Bishop, are part of what transpired, but they are certainly not the entirety of the Arthur Blok letter collection. Another, much larger, collection of 470 letters compiled by Blok, found its way to S. Peter Dance (Pain, 1976), who augmented the collection and deposited it at the Library and Archive, BM(NH), London, UK in 1975 (Thackray, 1995). It is described online as six volumes in two boxes spanning 1800-1960: “Collection of 620 letters, with some specimens of signatures, to and from malacologists and other naturalists, 18th century to circa 1960 / assembled mainly by Arthur Blok, added to by S. P. Dance” (NHMUK, undated). Slightly more detail is given by Thackray (1995), where some of the receivers, but not senders, are named, “A. Blok, S. P. Dance, O. A. L. Mörch, A. J. Peile, J. R. le B. Tomlin, R. Winckworth and others”, all but Otto Andreas Lowson Mörch (1828-1878) being contemporaries of Blok. Following communications with the Library and Archive, NHMUK, the authors have acquired a seventeen-page list of correspondents in their augmented Blok letter collection. It contains 534 names, and although it does not specifically state that it is a senders list (rather than senders and receivers), the fact that Tomlin is not present but is on the Thackray (1995) list as a receiver, suggests that it most likely is. Research of this additional archive is beyond the scope of this paper, but to aid interested researchers, the list has been reproduced in Appendix 3 with full interpretation of the names mainly using Coan & Kabat (2025). The names of those that also occur in the NMW Blok archive have been highlighted, showing that it is a near-complete overlap, with only Hadjid Farchad and John R. le B. Tomlin not on the NHMUK senders list. Lewis Worthington-Wilmer, a receiver on the NMW list, is also not mentioned. In Blok’s obituary written by Pain (1976), it is unclear when the larger letter collection was passed onto Dance, as it could have been a bequest or a gift during life. Personal communication with S. Peter Dance has confirmed that he acquired the collection when visiting Blok at his Rottingdean home, sometime during the late 1950s or early 1960s: “I had met Arthur Blok once or twice, at meetings of the Malacological Society, but got to know him more personally when he invited me to visit him at his home … where I stayed overnight ... Apart from examining his well curated shell collection, I particularly remember admiring his fine library of shell books....He asked me if I could be interested in a collection of original letters written by various shell collectors and students of the Mollusca and showed me a drawer full of them. Of course I jumped at the chance and became their new owner. A few years later I purchased, from the book dealers Wheldon and Wesley, a similar collection that had been accumulated by Ronald Winckworth (1884-1950), a well-known student of the Mollusca. Together with the Blok collection, this constituted a substantial archive that I thought should be preserved in a museum library.” Delving into the NMW Blok letters gives further detail of when such a visit probably took place. Dance writes to Blok on 6 January 1958, starting to make arrangements: “Sorry, I should have said first of all that I would love to come down to Rottingdean to see you! I would like that very much. It’s 7 years since I came before. I could manage most week-ends, but I suggest a week-day as I still have some leave left and trains are better then. Next week? What day best? There are many things to discuss.” This was during the period when Dance was curator at the BM(NH) and writing Shell collecting, an illustrated history (Dance, 1966); this extensive Blok archive would have provided an additional source of background information for such research. There is unfortunately no record of when Blok passed Bishop his batch of 126 conchological letters, but if the date of Dance’s visit is correct, Dance most likely acquired his portion first. Bishop would have only been in his early 20s when Dance is thought to have acquired his letters, and the most recent letter in Bishop’s collection was sent in 1958. It may be that those passed onto Bishop were acquired later by Blok, after this first donation to Dance, but it is perhaps more likely that Blok held back some examples, when passing the larger collection onto Dance, and continued to augment the remainder until it was given to Bishop, which could have happened any time before or after Blok’s death. Given the extent of Blok’s donation to HUJ, it seemed possible that further holograph material resided there, but Henk Mienis (pers. comm.) has confirmed that no such archive material was passed onto them: “No correspondence, like letters from other shell collectors were received. Here and there in his catalogues or in a few books he wrote that the correspondence with a collector or an author went to a museum (or well-known malacologist) ... His catalogues were preceded by information dealing with the persons from which he obtained material. That part of the catalogue formed the basis for my article in Haasiana.” Based on the information known to the authors, it can be summarised that Blok’s dispersed letter collection is made up of two major portions: the larger series, passed on from Dance to the BM(NH) in 1975, spanning c.1800-1960 (470 letters, plus 150 augmented by Dance); and the smaller series, passed on from Bishop to NMW by his wife in 2019, spanning 1883-1958 (126 letters). The subject matter of the letters is extremely varied. Aside from a few simple ‘thank-you’ notes, matters molluscan are dealt with to varying degrees of detail and complexity. In some cases, we find ‘chatty gossip’, but there is plenty of serious scientific discussion, together with a few pages that are best described as ‘molluscan notes’. Predominantly, the subject matter concerns non-marine species, reflecting Peile’s and Connolly’s main interest, but also that of senders such as Laidlaw and Watson. Many are to do with identification matters, but also shells were sent (for identification or for exchange), while quite a few concern radulae. As well as the content of the letters themselves, there is much of interest in how the recipients responded. Peile, in particular, appended extensive notes, comments and lists, in pencil. Clearly, this reflects the stimulation and sense of conchological comradeship that developed among postal correspondents, when this was the primary method of communication. The Cardiff connections centre around conchologists who were major donors to the NMW’s shell collection and those who were, or would become, curators at the museum. As mentioned earlier, one of Blok’s aims was to compile a complete set of papers written by James Cosmo Melvill (1845-1929) (Fig. 11a), whose shell collection now resides at NMW as part of the iconic Melvill-Tomlin collection. Blok referred to these reprints as “Melvilliana”, and one of his correspondents who helped him in the quest was the long-serving CSGBI secretary, John Wilfrid Jackson (Fig. 11b), whose father-in-law, Robert Standen (Fig. 12c), had collaborated with Melvill on numerous papers (notably those on the Loyalty Islands, the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea, the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition and the Falkland Islands). Jackson inherited a good deal of material from Standen and so was in a good position to fill in some of Blok’s “desiderata”.

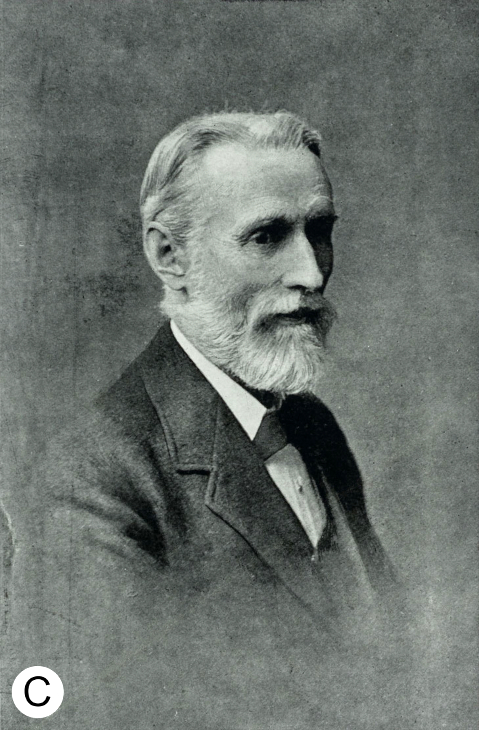

On 11 February 1933, Blok wrote to Jackson (BMAG archive): “I have been trying to complete – or make less incomplete – my set of Melvill’s papers, having acquired with Winckworth the remaining stock of separates which Dawsons of London held. To continue the task, I want some separates from the J. of C. and if by chance you have any stock of these separates, I should be glad to send a list of my desiderata. And in addition, there is one only of the Ann. & Mag. of N.H. papers which tantalisingly I cannot get, (viz. Ser 6, Vol. VI, Dec. 1890) and some of the Memoirs and Mem. & Proc. of the Manchester Lit. & Phil. Society. Do you know if there is any chance of getting these as separates at a reasonable rate? If so, I should be very grateful for any hint or reference which you could give me.” Blok clearly received a positive response from Jackson, although he felt a little conflicted, as he replied: “You suggest filling in my remaining Melvill gaps (or some of ‘em!) from your own library but why? Are you willing to be denuded & if so, what recompense can I make?” In addition to Jackson, Blok was also contacting others who stood a good chance of being able to help him on this mission. A letter from John Read le Brockton Tomlin (1864-1954), who had purchased Melvill’s collection in 1919, written to Blok during the same period, suggests that Blok had asked for such duplicates. It appears that Tomlin was also hoping to fill gaps in his own collection (dated 2 March 1933, NMW Blok archive): “Yes, it was the last copy of the Melvill list, but why not send it to you as much as to anyone? Very glad indeed that it is of some use…. My gaps in the Melvill series of papers are almost entirely early J. of C.’s with a few P.M.S.’s…. You haven’t any dup. papers of his ex J. of C. I fear? Have you that excerpt of his from the Manchester (?) Brit. Ass. Handbook?” In the same letter Tomlin mentions the death of Melvill’s wife, Bertha née Dewhurst (1853-1933), after whom Mitra berthae Sowerby III, 1879 and Ennea berthae Melvill & Ponsonby, 1901 were named. Finally, there is a letter from Ernest Ruthven Sykes (1867-1954) (Fig. 11c, 13a), Melvill’s son-in-law, to an unnamed correspondent, presumed to be Blok, which also refers to Melvill’s separates (20 May 1933, NMW Blok archive): “I don’t think I have any separates – all Melvill’s were sold after his death: I took some and the family sold the rest.” In the end, Jackson, always hard up, no doubt sold some of his separates to Blok, and both parties ended up satisfied. Blok finally achieved his aim, as he noted in a letter to Jackson (18 August 1945, BMAG archive): “When I was a bit younger & more enthusiastic, I set out to get all of Melvill’s papers & in fact I got them. It took me some years and much sleuthing but at last I completed them with the exception of an early [one] in the J. of C. which I hope to get a la photostat one of these days. The set makes an imposing row of bound vols., which, with a copy of a 60-page index of all M’s species from the Indian O. & Persian Gulf which Winckworth made, make a useful working tool.”

John Read le Brockton Tomlin (1864-1954) (Fig. 12a) had lived and worked in Cardiff from 1890-1899, teaching at the Llandaff Cathedral School, and this connection led him to bequeath the aforementioned Melvill-Tomlin collection to NMW. He writes to John William Taylor (1845-1931) on 22 January 1926 (CSGBI archive): “My idea as regards my own collection is to bequeath it to the Nat. Mus. of Wales, with as complete a library as my means will allow to accompany it. Cardiff is becoming a more & more important centre: I have many ties with it & I think that a ref. coll’n not very far behind that in the B.M., and a good library accompanying it, may be in the future an incentive to our hobby.” The arrival of the joint collection at NMW in 1955 completely changed the landscape of the pre-existing museum mollusc collection, containing an estimated one million shells, rich in types and historic material, alongside an exemplary molluscan library and extensive reprint collection. Tomlin and Blok were friends who corresponded and mixed in the same conchological circles, attending the same CSGBI meetings and working on the council together. Within the NMW Blok archive there are: 3 letters from Tomlin (2 to Blok and 1 to Connolly) and 6 letters to Tomlin (from Baden-Powell; Benthem Jutting; Haughton; Péringuey; Rensch; and, Schenck). In just two letters, the correspondence from Tomlin to Blok covers a great variety of subjects, in addition to the hunt for Melvilliana mentioned previously. There is discussion of Mauritian shell identification, requests of shells and offers of others, enquiry of Clausilia ‘type’ annotations in Blok’s copy of The Fauna of British India (Gude, 1914), procurement of books and expressions of interest in the malacofauna of oceanic islands, such as Christmas Island in the Indian Ocean, from where Tomlin was at that time identifying specimens.

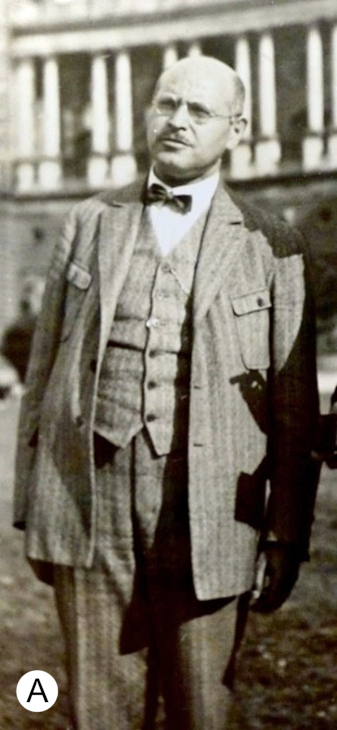

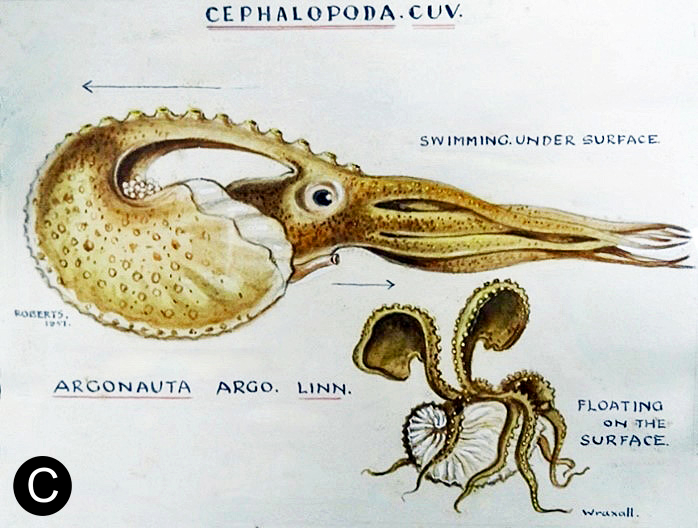

John Davy Dean (1876-1937) (Fig. 12b, 13a) was another stalwart of the CSGBI, whose paper on the Conchological Cabinets of the Last Century (Dean, 1936) remains an important reference in the history of conchology. He was a very important actor in the development of the NMW shell collection, working as Assistant Keeper of Zoology for nearly twenty years, between 1918-1937. There are three letters relating to Dean in the NMW Blok archive, the one mentioned earlier sent to Blok from Dean and two others sent to Dean, one being a mere acknowledgement note from Guy Coburn Robson (1888-1945). The second is a letter sent from Melvill to Dean in 1927, which superficially appears to be a simple note about sending a batch of reprints. However, the reprints were the list of William Evans Hoyle’s (1855-1926) (Fig. 13b) malacological papers, compiled and published by Melvill (1926), following Hoyle’s death the previous year. In his letter, Melvill also asks for Mrs Hoyle’s address so that she can have some copies and distribute them amongst his friends. Hoyle was important in the lives of both men and forms another part of the Cardiff connection: he was the first Director of NMW from 1909 and active in the design of the building, where over 450 lots of his fluid-preserved cephalopod collection still reside, including those from major 19th century and early 20th century expeditions (Challenger, Porcupine, Triton, Albatross, Knight Errant, Investigator, Skeat, Virginia, Scottish National Antarctic Expedition, Nora Niven, Siboga, Scotia). It was he who appointed Dean to the Assistant Keeper of Zoology role at NMW, where they worked together between 1918-1924, until Hoyle retired due to ill health. The final Cardiff connection is that of S. Peter Dance. Dance was another Keeper of Zoology at NMW, but for a much shorter period than Dean; he worked there from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, having already had curatorial positions at the BM(NH) and Manchester Museum, not to mention publication of his world-renowned book, Shell collecting. An Illustrated History, in 1966. There is only one letter in the NMW Blok archive relating to Dance, which has already been referenced in this paper; the one from Dance to Blok on 6 January 1958, where arrangements to visit Blok in Rottingdean are discussed. Dance is excited about Clausiliidae in this letter; Blok appears to have sent him notes from Tomlin on the matter and possibly specimens as well. Dance is keen to bring his own self-collected Cypriot Clausiliids to compare with those in Blok’s collection and lists several Albinaria species he is particularly interested in seeing. As many of the letters were written in and around the time of WW2, it is not surprising that the conflict is frequently mentioned, and the details included amount to a mini social history of the times. The comments are diverse. The immediate horror of the bombing is exemplified by an excerpt from James Eddowes Cooper (1864-1952), a longstanding member of the UK’s two main mollusc societies, written to Peile in 1945: “It is too early yet to be sure, but we do hope that there will be no more V.2’s. The first half of last week was a trying time. My wife had some sleepless nights. One bomb fell into the sea off Chestfield, another smashed up Elham near Canterbury.” Other references are more obscure. Following the War, in 1947, Woutera Benthem Jutting discusses the postage stamps illustrated by the fascist-leaning Pyke Koch, that circulated The Netherlands during the conflict (Fig. 14), and the relief felt when the Queen’s portrait was returned. She writes: “The stamps sketched on the accompanying sheet were issued during the German occupation. The horses, swans, trees are Nordic (Germanic) symbols of folklore: tree of life, horses of Wodan [the supreme deity, related to the Scandinavian god, Odin], &c. of which the Nazis “schwärmed” [swarmed] at every possible and impossible occasion. You will certainly have such designs in England too, in old Saxon farms, and objects of arts and crafts. It is true they were well designed by a nazi-painter (a Dutchman), named Pyke Koch. But you understand that we were glad when the issue was taken out of circulation and we have the familiar portrait of the Queen again.”

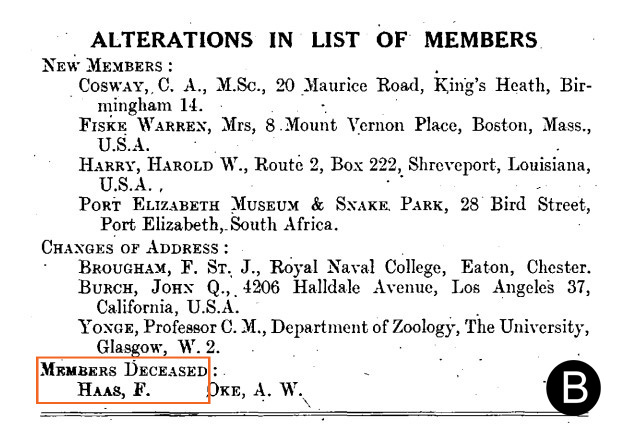

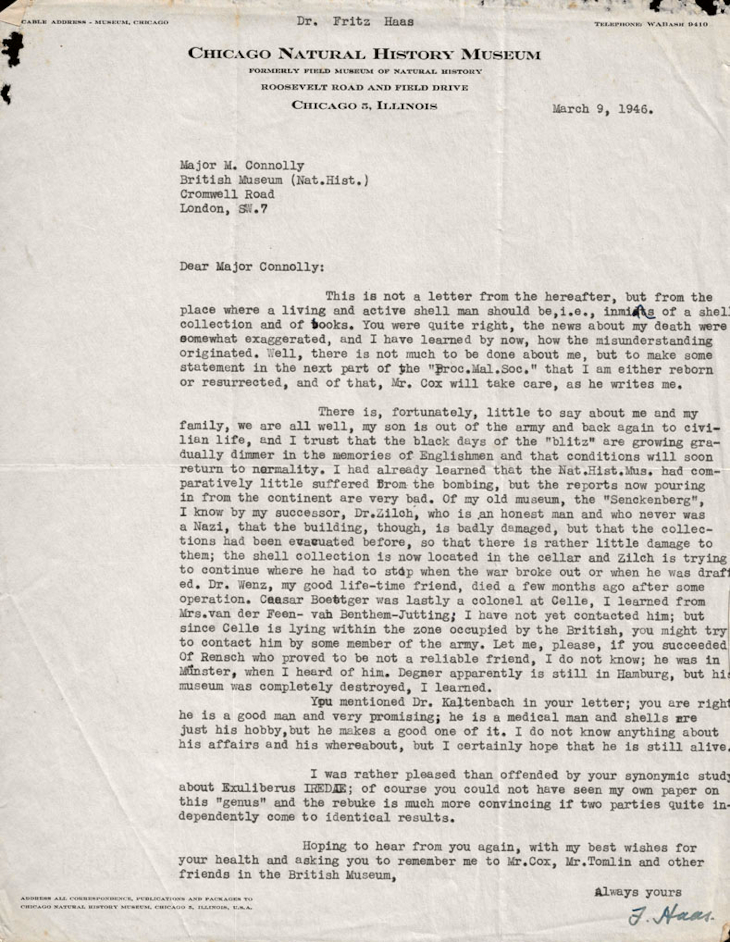

As a British Jew and Zionist, Blok may have felt a particular connection to others who shared his views, such as Fritz Haas (1886-1969) (Fig. 15a) a German-born Jew who narrowly escaped the Nazi regime at the War’s onset and moved to Chicago where he became a naturalized U.S. citizen (Solem, 1970). In a letter to Major Matthew William Kemble Connolly (1872-1947) dated 9 March 1946 (Fig. 16), Haas writes from Chicago: “I trust that the black days of the “blitz” are growing gradually dimmer in the memories of Englishmen and that conditions will soon return to normality. I had already learned that the Nat. Hist. Mus. had comparatively little suffered from the bombing, but the reports now pouring in from the continent are very bad.” He goes on to provide much detail about old colleagues from Senckenberg and other German museums caught up in the war, and the fallout from the Nazi persecution: “Of my old museum, the “Senckenberg”, I know by my successor, Dr. Zilch, who is an honest man and who never was a Nazi, that the building, though, is badly damaged, but that the collections had been evacuated before, so there is rather little damage to them; the shell collection is now located in the cellar and Zilch is trying to continue where he had to stop when the war broke out or when he was drafted”. Of Eduard Degner (1886-1979), he says: “Degner apparently is still in Hamburg, but his museum was completely destroyed, I learned.” Haas writes less warmly in reference to Bernhard Carl Emmanuel Rensch (1900-1990), “who proved not to be a reliable friend”, although no explanation is given. Ernst Mayr (1992), the famous evolutionary biologist, asserts that Rensch was dismissed from Berlin Museum because he would not join the Nazi Party, and found a position in the Zoological Garden in Münster instead, but his recall to the military from c. 1940-1942 (Rensch, 1980: 297) may be the cause of Haas’s dismay. Haas, incidentally, was falsely reported to have died in the war and assures Connolly that he is not writing from the grave at the start of his 1946 letter: “This is not a letter from the hereafter, but from the place where a living and active man should be, i.e., in midst of a shell collection and of books. You were quite right, the news about my death were somewhat exaggerated, and I have learned by now, how the misunderstanding originated.” The misunderstanding that he refers to is in fact a notice in the Proceedings of the Malacological Society (Anon, 1944), pronouncing his death (Fig. 15b).

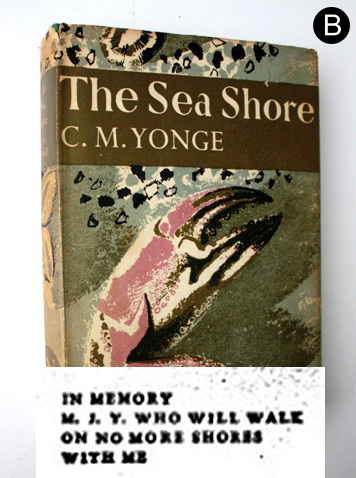

Another war-related letter is from Charles Maurice Yonge (1899-1986) (Fig. 17a) to Guy Lawrence Wilkins (1905-1957), dated 15 September 1942. Yonge was an exemplary researcher with a particular interest in the form, function and evolution of bivalves (Morton, 1992), whereas Wilkins was a talented natural history artist (Fig. 18), model maker and mollusc curator at the BM(NH) (Blok, 1957; Topley, 2019). On the face of it, this is a short, polite thank you for some drawings of Tridacna that Wilkins had sent from his address at 828 Company, Shirehampton Camp, near Bristol, UK. Addressed from the Department of Zoology, Bristol University, there was, however, a poignant story about to unfold. With Bristol a target for enemy bombers, the Yonge family (wife Mattie and two youngsters – Elspeth (b.1931) and Robin (b. 1934)) had been evacuated to the small coastal town of Burnham-on-Sea, about 30 miles away, while Yonge himself had also decamped – to the relative safety of the former darkroom, in the Zoology Department basement (Morton, 1992)! Serving army officer Lieut. Corp. G. L. Wilkins had clearly been based at Burnham in the past as Yonge commented: “You will have trouble getting back to Burnham again because the billets your people occupied have now been taken over by American [soldiers] and the town is much more lively than it used to be.” While their situation at the time was difficult, the Yonge’s were about to experience a much more challenging problem. Later in 1942, Mattie became seriously ill and this, together with her desire to return to Scotland, led Yonge to accept the Regius Chair at Glasgow in 1944 (Morton, 1992). Sadly, she died shortly after they moved. When Yonge wrote The Sea Shore (first published in 1949), he touchingly dedicated the book: In memory M. J. Y. who will walk on no more shores with me (Fig. 17b).

Later, in 1958, his daughter Elspeth would assist him by producing many of the illustrations in his co-authored book, Collins Pocket Guide to the Sea Shore (Barrett & Yonge, 1958). As an aside, Blok and Wilkins were clearly friends, both CSGBI council members at the same time; Blok wrote Wilkins’ obituary in 1957, which is full of warmth as he writes: “His death entails a grievous loss to conchology and to the wide circle of his friends and correspondents alike, for he was well-esteemed by all who knew him. There was nothing “starchy” about him. He was genial, witty, modest and an excellent mimic, but a thorough, competent and careful worker in his subject withal. He was patiently and willingly at the disposal of anyone who consulted him, and was most generous with his time and his knowledge.”

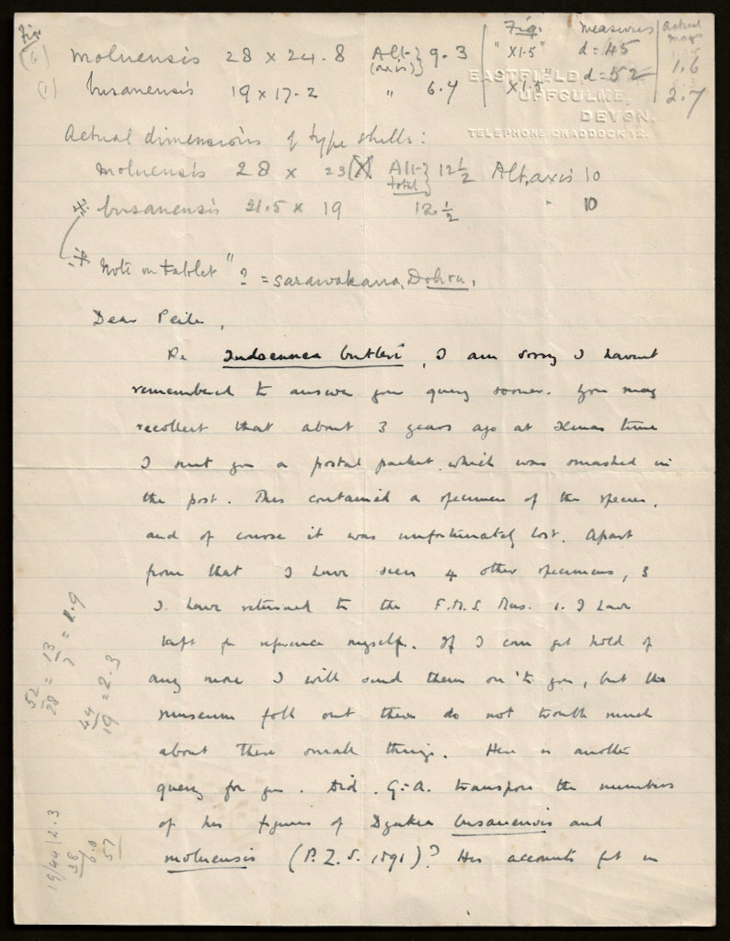

Coincidentally, one of the authors (BJG) taught at Portway School in the 1970/1980s, across the road from the remains of the Nissen huts that made up the Shirehampton Camp where Wilkins was based. Taxonomic ‘to-and-fro’ often features in the letters. The 1920s to 1940s was a period when material was becoming more available for study from around the world, and much attention was being given to relationships. The series of letters from Frank Laidlaw are particularly interesting in this respect. Debates raged, opinions were formed (and amended), colleagues were criticised, and eventually something acceptable (to the majority at least) emerged. It must have been a stimulating environment. A few excerpts from Laidlaw’s letters give a flavour: “I am hoping to revise Dyakia soon. That genus should be reserved for sinistral forms only. I find some of Gude’s genera (Asperitas etc.) rather a difficulty.” “I have just got from Boden Kloss the types of Ekendranath Ghosh, n. spp. from the Selang Caves. In my opinion Ghosh has committed a regular howler.” “I have written to Tomlin and sent him one or two puzzles in regard to Everettia.” “By the way I find that friend [Johannes] Thiele has overlooked the genus Sarika altogether in his Handbuch. And it is a perfectly good genus.” “Can you help me over the enclosed Discartemon. It is exactly like Collinge’s sykesi, only about half the size. I have seen the type of sykesi and this specimen is much more like the type than it is like the rather poor figure Collinge gives.” “At the risk of boring you badly I am enclosing firstly a rough outline of what I have been able so far to make of the Zonitidae.” “Did G.-A. [Godwin-Austen] transpose the numbers of his figures of Dyakia busanensis and moluensis (PZS 1891) [Proceedings of the Zoological Society]? His accounts fit in much better with the figures if one takes it that way.” Clearly Laidlaw, an amateur, had a huge range of contacts, and was confident in expressing his views. Unfortunately, as is so often the case with archive letters, we only have Laidlaw’s side of the story. We can see from numerous penciled annotations on the letters (Fig. 19) that Peile was fully engaged in the debates. How much more might be revealed by Peile’s formal responses!

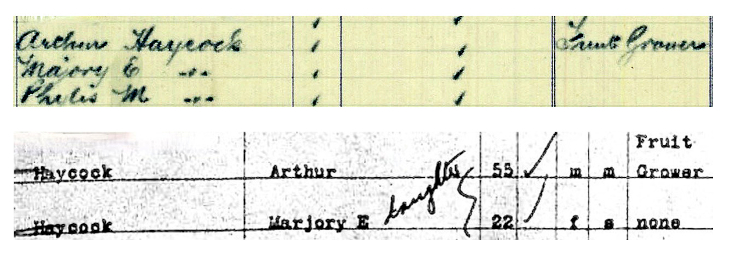

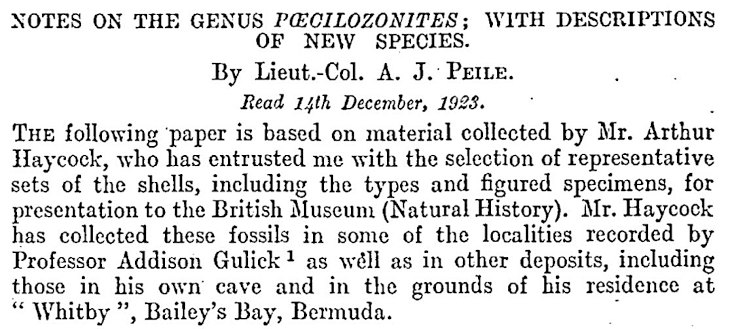

Taxonomists over time – Peile and Haycock In several cases, relationships can be traced through a combination of letters and publications that together build a bigger picture. The relationship between Lieut. Col. Alfred James Peile (1868-1948), the most represented receiver in this archive, and Arthur Haycock (1863-1934), a British-born fruit grower (Fig. 20) and amateur conchologist who lived in Bermuda, is one example worth mentioning.

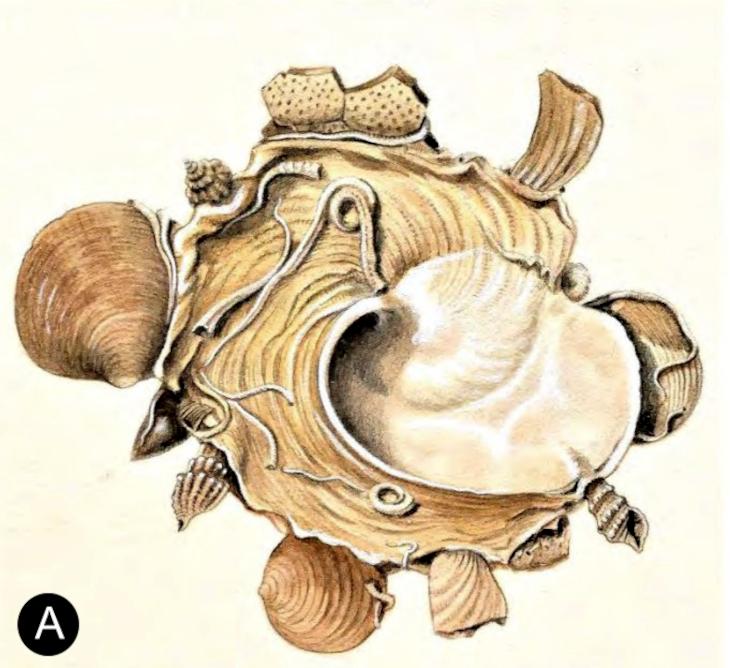

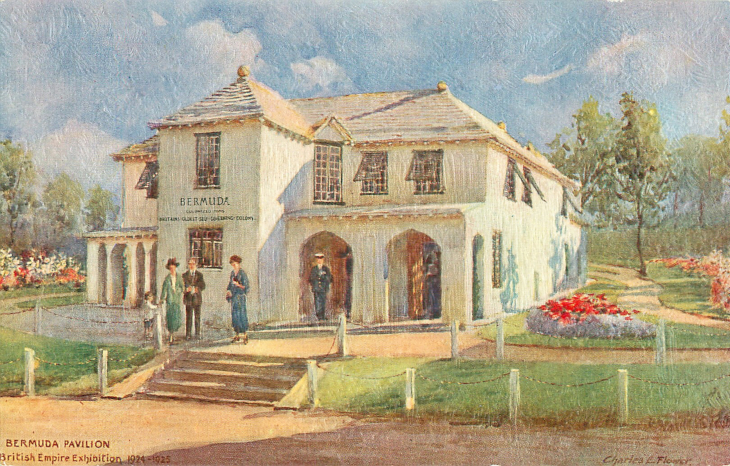

Peile was famed for his work on radulae, “in the preparation of which he developed great skill and an almost perfect technique” (Anon, 1948; Winckworth, 1949), and radulae are central to the discussions in most of his letters. However, his other great passion was for the shells of Bermuda, and this is where his connection with Haycock lies. Peile’s association with Bermuda began in 1907, when he served there in the Royal Artillery until 1911, and here he compiled “an excellent series of shells” (Winckworth, 1949). In addition to donating some of his best Bermudian specimens to the BM(NH), he prepared a show case for display at the Bermuda Pavillion during the 1924 British Empire Exhibition in Wembley (Fig. 21) and presented on The Mollusca of Bermuda to the Malacological Society of London, for his Presidential address in 1926 (Peile, 1926). Interestingly, Haycock also refers to the Bermuda Pavillion in his letter of 10 July 1924, having been asked to send his collection all the way from Bermuda to Wembley! It seems that he declined, saying to Peile, “Glad you are doing what you can for them”.

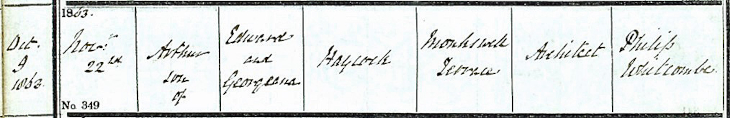

There is very little information available on Arthur Haycock; he is not listed in the Winckworth card index housed at the NHM, London and only a short entry has recently been added to Coan & Kabat (2025). There are no letters to or from him in the NMW Tomlin archive, although there are twelve Bermudian shell lots originating from him in the Melvill-Tomlin collection (NMW), and possibly more that are yet to be discovered. He is, however, named in the NHMUK Blok archive’s ‘list of correspondents’ and no doubt this will contain further direct correspondence between Haycock and Peile. Glimpses of Haycock’s life can be brought together from various sources. His baptismal certificate (Fig. 22) includes a date of birth – given as 9 October 1863.

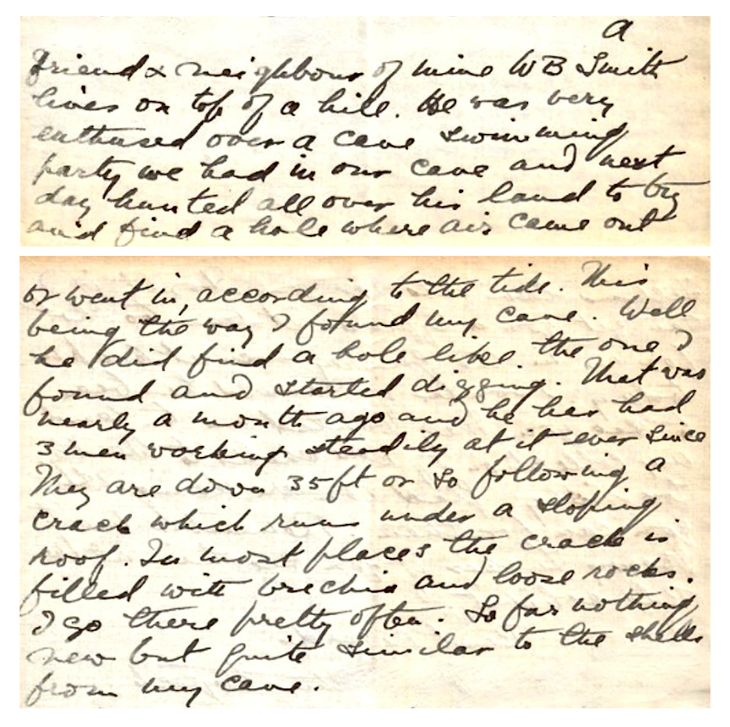

This is confirmed in his letter of 28 December 1933 (NMW Blok archive), where he shares the celebration of his 70th birthday with Peile: “Oct 9th I had a birthday celebration. My cake had 70 candles on it which I was supposed to blow out in one breath. It took about three.” Arthur was born in Shrewsbury and baptised at the Anglican parish church of Holy Cross (Shrewsbury Abbey). In 1871, at seven years old, the census shows he was at school in Shrewsbury, whilst living with his parents (the architect Edward Haycock and his wife, Georgiana) and four siblings (Eleanor (14), Agnes (13), Henry (12) and Mabel (1)) at 3 Monkswell Terrace, Abbey Foregate, Shrewsbury, UK. Ten years on, the 1881 census shows Arthur to have moved to London; he was a boarder at 99 Guilford Street, Bloomsbury and is recorded as an “Army Student”. There is then a gap of thirteen years, where no obvious records can be found, but we know from his obituary (Anon, 1934) that he arrived in Bermuda in 1894 and married resident Mary Logier Hollis on 9 October 1895 (Anon, undated). Mary and Arthur had four children: Marjorie 1 Eleanor (1896-1950); Hilda Gwendolyn (1900-1906); Phyllis Marianne (1908-1996); and Arthur Elystan (1910-2005). An obscure article written by Haycock in 1899, helps to fill the gaps a little. Published in The Gardeners’ Chronicle, he wrote about the Bermuda Juniper but also gives mention to living in Florida for ten years and a visit to the Bahamas (Haycock, 1899). Whether his profession during this period was as a fruit grower is unknown at present: “I have lived for ten years or so in Florida, and have "hunted" and camped in the great Gulf-hammock. This is where the Cedars are cut for the large pencil-mills at Cedar Keys. We used to burn large branches of these felled trees for our camp-fire, and would have gladly used any other kind of wood because it invariably "spluttered" and sent large pieces of burning coals flying all over our camp, and we had often to get up in our blankets and stamp out the fire….The Bahama Juniper I never noticed, but I brought a stick from there made of the wood, and had a handle made for it, of J. bermudiana. There seems to be no distinguishable difference between the two woods.” We know that Haycock lived at Whitby, Bailey’s Bay, Bermuda, where his letters were all sent from. Outside of his malacological interests, Haycock was known in Bermuda, amongst other things, for the discovery of the Wonderland Cave (now called Fantasy Cave) on his own land. Alongside its neighbouring Crystal Cave, it is reportedly still one of the major attractions on the island today, with spectacular stalagmite formations and crystal-clear waters (Fig. 23). In his letter to Peile dated 10 July 1924, he mentions that it was discovered when finding a hole “where air came out or went in, according to the tide”. This discovery was in 1907, and articles in The Royal Gazette (Anon, 1907a; Haycock, 1907) give a peek into the early explorations of the caves with only candles for light and fishing lines to secure the explorers. From July to September that year much work was carried out by Haycock’s team as, by the September, an article written by “a grateful guest” reveals a cave-scape brilliantly lit by over a hundred lights with a railed staircase leading down 70 feet (Anon, 1907b). The writer is effusive about their visit to this glittering subterranean fairy scene and considers Mr Haycock “the fortunate possessor of this wonderous gift of the Gods”. Two years on, the Haycock’s opened their home and cave to host a community bazaar to raise money for the building fund of the local church, during which over 300 people visited the cave (Anon, 1909b).

Although Haycock was inviting guests early on, it was five years after its initial discovery that it was officially opened to the public as a show cave (Anon, 1912; Oldham, 2002). Haycock clearly continued to make use of it himself, as shown in the 1924 letter to Peile where he refers to “a cave swimming party we had in our cave”. Apparently, this provoked jealousy in one of his friends and neighbours, who went hunting for his own cave and found one! Haycock was not only excited by the find of the caves, but also by the discovery of numerous shells uncovered during their digs (Fig. 24), which he knew from experience were plentiful in the caves and caverns of the island (Vanatta, 1924). The specimens discovered in his own cave in the grounds of his residence are cited from the locality ‘Whitby cave’, which is the type locality for the fossil Strobilops pilsbryi Morrison, 1953 (now synonymised under Discostrobilops hubbardi (A. D. Brown, 1861)), posthumously described from Haycock’s material, sent by him to USNM during his life.

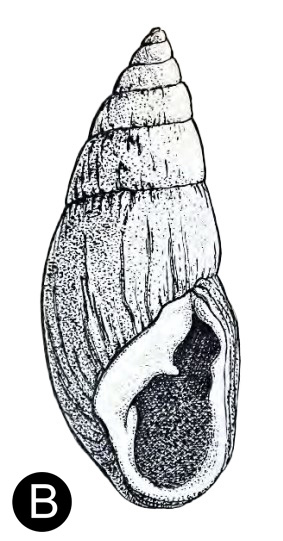

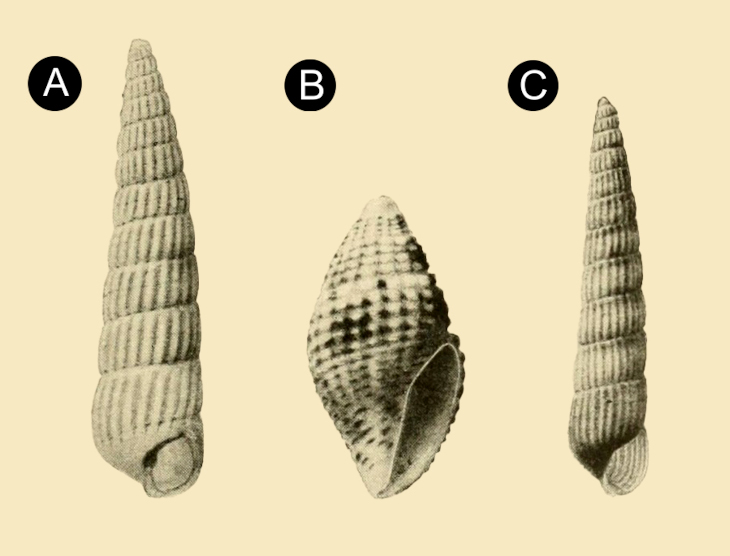

Haycock was a keen collector of both modern and fossil Mollusca on the island. He had his own catalogued collection, but also shared his material amongst specialists, notably Dall and Bartsch (1911), Vanatta (1912), Peile (1924; 1926) and Gulick (NMW Blok archive). Peile also passed on some of Haycock’s ‘pickled’ material to others such as Hugh Watson (1885 -1959) - Haycock being described as Peile’s Bermudian “standby” in Watson’s letter dated 26 September 1928. Pilsbry (1924) also cites him as a collector of Bermudian fossil snails and discusses material from Whitby Cave. Haycock was clearly an important source for specimens from the island and was well connected with American conchologists: whilst preparing shells to donate to the local museum in Hamilton, Bermuda, Haycock sent specimens to Dall for identification, and many proved to be new to the island or new to science (Dall and Bartsch, 1911). Dall writes: “There are doubtless numerous other small species at Bermuda still to be obtained which have not yet been recorded, and it is to be hoped that Mr. Haycock’s success in adding to the known fauna may stimulate others to continue exploration in the same line.” Furthermore, Haycock was sufficiently well-regarded by Dall to have had several species named after him including: Argyrodonax haycocki Dall, 1911 – a new genus of bivalve; Turbonilla haycocki Dall & Bartsch, 1911 (Fig. 25a); and, Mitromorpha haycocki (Dall & Bartsch, 1911) (Fig. 25b), originally Mitra haycocki.

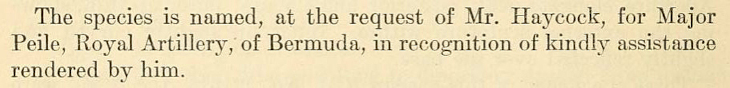

Peile (1926) also shows gratitude to Haycock when publishing The Mollusca of Bermuda: “It could not have been completed without the kind help of Mr. A. Haycock of Bermuda, who has not only furnished me with the catalogue of his own collection, but has also been indefatigable in correspondence, sending me invaluable notes and information, as well as specimens” Although the four letters to Peile in the NMW Blok archive are from Haycock’s later years, spanning from 1924-1934, we know they met much earlier, when Peile was stationed there between 1907-1911. This is first evidenced in 1909 when Major Peile and his wife were listed as guests at the community bazaar hosted by the Haycock family (Anon, 1909b). This was followed by the species description of Turbonilla peilei Dall & Bartsch, 1911, which was dedicated to Peile at the request of Haycock (Fig. 25c, 26) “in recognition of kindly assistance rendered by him”.

Later, Peile (1924) published on the endemic genus of Bermudian snails called Poecilozonites, based on specimens he had received from Haycock (Fig. 27).

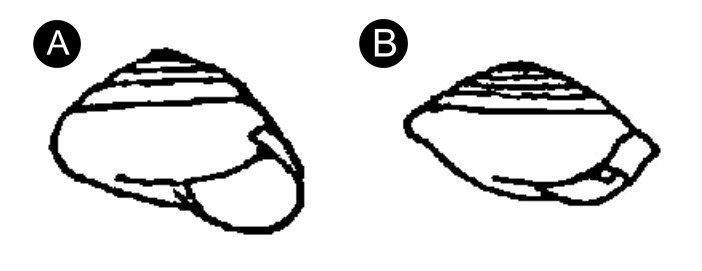

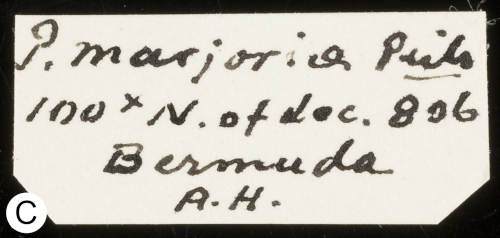

The paper appeared in the Journal of Molluscan Studies (Peile, 1924) and amongst the new species were Poecilozonites haycocki (Fig. 28a) and P. marjorae (Fig. 28b). The former named after Arthur, and the latter named after Arthur’s daughter Marjorie (1896-1950) who “explored the locality and collected the specimens”. Haycock in fact mentions two of his daughters in his letter dated 14 December 1924, “Marjory and I leave here on the 23rd for a trip through the West Indies” and “Phyllis has her school report sent to us. She has ‘excellent’ for everything. A bit different to my reports as far as I remember them.” Nine years on, Haycock writes that Phyllis (1908-1996) had married (to Percy) and had her first child, a “fine boy” called Miles Everest Hastings Outerbridge.

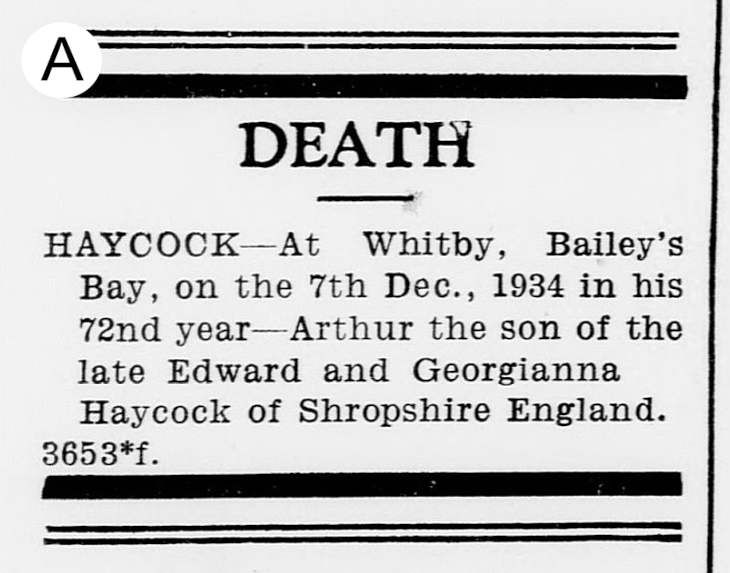

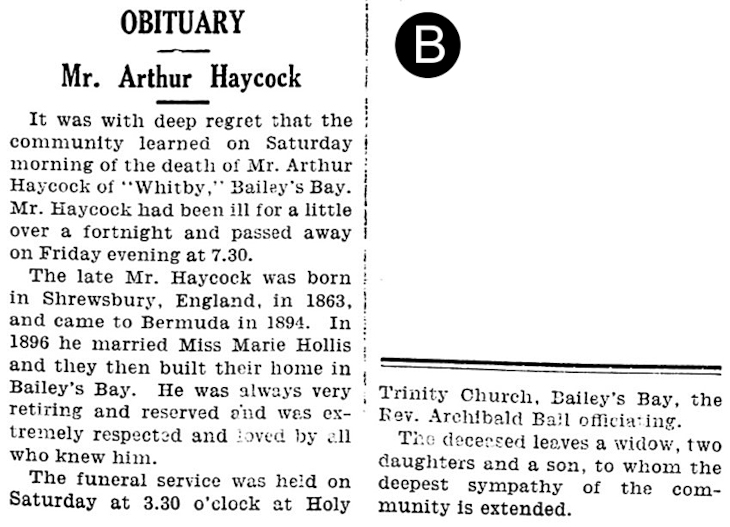

Arthur Haycock died on 7 December 1934, having been ill for a fortnight, and a death notice and short obituary notice were published in The Royal Gazette (Anon, 1934) (Fig. 29a, b). Although described as retiring and reserved, it is clear from both his correspondence and the articles published during his life that he and his wife were central to a thriving community and that he had a great passion for collecting both modern and fossil shells, making significant contributions to the knowledge of the malacofauna of Bermuda. It is worth noting that the last letter from Haycock to Peile in this archive is from March of the year he died.

Published information relating to Haycock’s shell collection in Bermuda is rather fragmented. There are mentions in various articles in The Royal Gazette, published during his life – in 1909, advertisement for the bazaar describes his collection of marine shells as holding over 180 varieties (Anon, 1909a). By 1913, it is described as containing more than 600 varieties and was pronounced to be “the finest in the entire world” and “a sight that will be long remembered” (Anon, 1913). Around the same period Haycock was sending material to American institutions, in particular ANSP and USNM (Dall & Bartsch, 1911; Vanatta, 1912). Abbott & Jensen (1967) list Haycock’s collection in BAMZ as one of the four institutions where there are thousands of representatives of Bermudian shells. There is even a mention of Haycock’s collection given by Stephen Jay Gould when he publishes on an unusual Bermudian pond, praising the “availability of abundant comparative material in the magnificent collection of Mr. Arthur Haycock (Bermuda Museum)” (Gould, 1968). Later, there is transfer of important type material, when some of Dall and Bartsch’s type specimens were transferred from the BAMZ to NMNH. This is recorded by Rosewater (1984) as they were originally published as being in the Bermuda Museum, or in the collection of Mr. Arthur Haycock, of Bermuda. Communications with the BAMZ has revealed that there is uncertainty in the location of Haycock’s collection between the time of his death in 1934 and its arrival at the museum by 1962. Their records show that it was passed to the museum by Charles (Gussie) Baker and perhaps it is most likely that it remained with the family until that point, although this is not confirmed. Although Arthur’s wife died in 1941 (Anon, 1941), two of their children, Phyllis and Arthur Elystan were still alive and living on the island well beyond the 1960s. The collection is currently undergoing documentation and repackaging into archival storage. Jennifer Gosling has reported (pers. comm.) that it was originally stored in custom-made wooden cabinets with 32 drawers full of shells; they were displayed in shell boxes or loose in drawers with dark blue cotton wool used to cushion the drawers and to keep the shells in place. As is a common story, there has been some displacement and separation of the shells and labels over time, but work is being undertaken to reconstruct the collection as much as possible, whilst moving it to more appropriate storage and undertaking the inventory process. More detailed information will be available about the collection once this task has been completed. Finally, we will end with an amusing inclusion from Woutera van Benthem Jutting in a letter to J. R. le B. Tomlin (16 October 1934, NMW Blok archive). Here she mentions a Dutch colleague who was … “…. studying the life history of the Loch Ness monster and asked me what the animal’s diet could have been. I transmitted the question to Prof. Boycott in his function of Hon. Recorder of the Conch Society, but he could not inform us (or perhaps thought it safer to keep away from such a dangerous question!).” Tomlin’s reply is not recorded, but one might guess that he felt the same way as Boycott! |

|

Arthur Blok demonstrated remarkable persistence and diligence in all areas of his collecting, including in his compilation of conchological letters. He recognised their importance as tools to interpret handwriting in collections and as insights into the history of shell collecting and taxonomic debate. The breadth of stories and themes that can be extrapolated from a relatively small collection of correspondence, such as his archive now in Cardiff, has been illustrated but is not exhaustive. Online publication of this material will offer cross-disciplinary researchers access to an important resource that can be further interrogated and interpreted. Collections of letters such as this one may not provide a detailed correspondence network of a single figure (as can be seen with the Crosse archive (Breure & Audibert, 2017) and Paulucci archive (Talenti et al., 2024)), but each letter enriches our understanding of the actor-networks in the field, gives valuable insight into the personalities involved and contributes incrementally to our knowledge of natural science history. |

|

We would firstly like to thank Anne Bishop and her family for making the Arthur Blok archive available and for Anne’s time, conversation and hospitality; also, Ben Rowson (NMW) who was an integral part of the visit to Anne’s home and the discussions we shared. We thank Henk Mienis for his generosity in sending references relating to Arthur Blok and for answering questions about the Blok donation to the HUJ; we thank S. Peter Dance for sharing his memories of the time he spent with Arthur at his home in the 1950/60s; and Andreia Salvador and the Library & Archives at the NHMUK for making the portraits of Blok and Dean available and the list of correspondents in their augmented Blok archive. We are grateful to Dan Robertson at Brighton & Hove Museums for giving us access to the 1973 audio recordings of David Clitheroe interviewing Arthur Blok about his varied career. Relating to the research around Arthur Haycock, we would particularly like to thank Jennifer Gosling for the information she shared about the Haycock collection at the Bermuda Aquarium, Museum and Zoo and about Haycock’s life; and Struan Smith, also from BAMZ, and Jane Downing from the National Museum of Bermuda, for their help with information on Arthur Haycock. Finally, we would also like to thank Susan F. Jones for her help with translation. |

|