A story of Taku and Mitqal. The akan weighing system, part three

Histoire de Taku et de Mitqal. Le système pondéral akan, troisième partie

- Jean-Jacques Crappier

|

A dozen testimonials about the Akan ponderal system, between the beginning of the 17th century and the end of the 19th, mention taku (and /or damma), and sometimes a double system of weight, but probably report just that what the Akan showed them. Weak system against portuguese weights, strong system against dutch and english weights, then again weak system at the end of the 19th century when the gold dust became scarce and of less good quality. The founding role of mitqal is also questioned in favor of a likely coincidence between the Arab and Akan weight systems. In addition, the value of 4.4 g attributed to it would not have been established in the context of the trans-Saharan trade, but later after the arrival of the Europeans, to adapt to their weights. Keywords: akan - ashanti - baule - gold weight (goldweight, goldgewitch) - Ghana - Côte d'Ivoire - Gold Coast - dualistic system - ethnomathematics - Timothy Garrard - Henry Abel - taku - ba - mitqal - proto-currency Du début du 17e à la fin du 19e siècle, une douzaine de témoignages font état du rôle que tenaient les graines de taku et/ou du damma dans le système pondéral des Akan, et parfois d'un double système poids-faibles/poids forts. Ils n'en rapportent cependant que ce que les Akan en montraient, système faible avec les Portugais, système fort avec les Hollandais et les Anglais, puis à nouveau système faible à la fin du 19e siècle quand la qualité de la poudre d'or eut baissé. Le rôle fondateur du mitqal est par ailleurs remis en question au profit d'une convergence entre les systèmes pondéraux arabes et akan. De plus, la valeur de 4,4 g qui lui est attribuée ne se serait pas établie dans le cadre de la traite transsaharienne, mais plus tardivement après l'arrivée des Européens, pour s'adapter aux poids de ces derniers. Mots clés : akan - ashanti - baoulé - poids à peser l'or - Ghana - Côte d'Ivoire - Gold Coast - système dualiste - ethno-mathématiques - Timothy Garrard - Henry Abel - taku - ba - mitqal - proto-monnaie |

Let us summarize Garrard's thesis

|

This article is the third in our series on the study of Akan gold weights. In our princeps publication (Crappier et al., 2019), we showed, by studying the largest collection of geometric weights ever studied (9031 including 298 head weights over 80 g) that the Akan weighing system (AWS) was of African origin. But our demonstration, which is based only on metrological arguments, goes against the thesis of Timothy Garrard (Garrard, 1980), which derives it from the Arab weight system, on historical and ethnological arguments and some archaeological clues, which is the authoritative thesis. So we looked at historical sources to see what they could tell us that was different about the origin of the AWS.

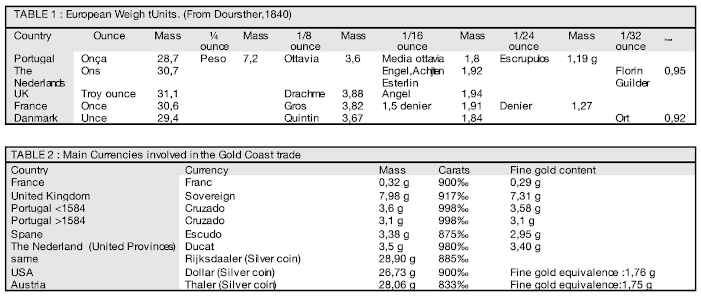

The question of the nature and the mass of taku is the central problem of our investigation of the Akan Weighing System (AWS). Has it varied over centuries, places or witnesses? Are there several taku? A heavy and a light? Jointly or separately? What seeds corresponded to him? Did taku even really exist? What do the sources say about this? To answer these questions, we looked for testimonies, accumulated since the 17th century, from Dutch, English, French, German and Swiss informants. We present them in chronological order, distinguishing between first-hand accounts, when we have been able to access the source document, and second-hand accounts, when they are reported by modern authors. We only retained from these authors the direct or indirect information on the seeds, as well as those which report a double system of weights (dualism). We will then wonder about the mitqal, of which Garrard made the cornerstone of the AWS by taking up his reasoning step by step. Akan units will be noted with our usual abbreviations: Light taku (≈ 0.22 g) noted T, heavy taku (≈ 0.25 g) noted T*. The main weights and currencies of Europeans involved in Akan gold trade are listed in table 1 and 2 (Annex)

The taku exists. Most witnesses state it, whether or not associated with damma. 1602. De Marees: 1668. Dapper: 1676. Muller: 1678. Barbot: 1704. Bosman: 1817. Bowdich: 1848. Bouët-Willaumez : 1852. MacLean, 1868; Horton, 1868, quoted by Garrard: 1874. Bonnat; 1875. Kuhne et Ramseyer, quoted by Menzel: 1875. Christaller : 1889. Binger : After 1900. Garrard and Abel:

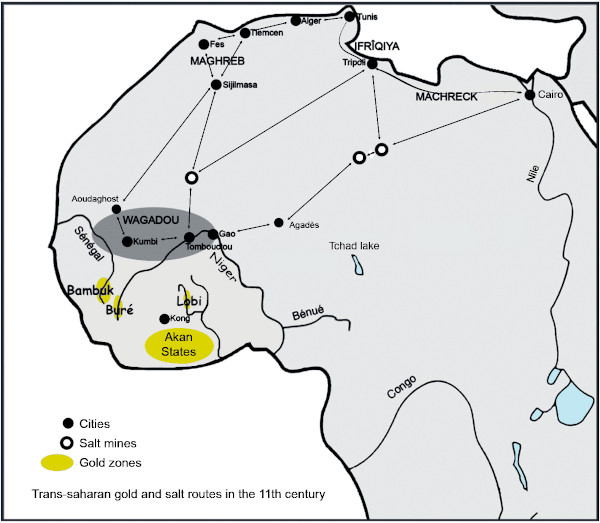

Out of 12 recorded testimonies, only 3 make no mention of the seeds, those of Dapper and Barbot, and that of Bouet (who however quotes the takon) but all speak of ake, as 1/16 of an ounce. Dapper, Barbot and Binger directly point to a dualistic system, which is also reflected in the inconsistencies of the other lists. We are in fact in the presence of two closed systems, which communicate only through commercial transactions. The Akan system on the one hand, the European system on the other. Akan operate at constant price and variable weight, Europeans at constant weight and variable price. We only have information on the first through the second. On the one hand, are internal transactions between Akan through the exchange of gold dust. Regardless of its purity they are not able to assess it with precision. Once the quality of the gold is deemed acceptable by both parties, only counts the difference between the weight of the buyers and the weight of the sellers. For the retail trade which makes the bulk of sales between Akan, they use the small weights 6. For wholesale trade with Europeans, Akan merchants use the highest values, benda or beyond, using those of their weights which correspond to those of their interlocutors. On the other hand, the Europeans. We will choose the English because they are the ones on which we are the best documented. Their currency, the Sovereign, is stabilized since 1816 at 8 g of gold at 916 ‰ (22 carats) or 7.32 g of fine gold. Their aim is to acquire gold in exchange of goods which they have paid for in £ to their suppliers. They calculate their profit in that currency, taking in account the purity of the gold ore they get as payment. They weigh it in troy ounces, with their scales and weights, but they cannot impose their weighings because their interlocutors are able to verify the transactions with their own apparatus. It is on this occasion that information on the respective weight systems is exchanged. Each European therefore only needs to know the part of the Akan system that corresponds to his weights. If we can easily understand that the transactions were made with the Portuguese in the light system (onça of 28.7 g), then with the Dutch and the English in the heavy one (troy ounce of 30.6 and 31.1 g), It remains to be explained why in the last quarter of the 19th century the light system was again resorted to. Things happens as if Akan gold had been devalued from 925 ‰ (22.2 carats) to 800 ‰ (19.2 carats) which can be explained by the rarefaction of natural gold dust, the purity of which exceeds 22 carats, and its replacement by nuggets, of lesser grade, or artificial powder as the Ashanti knew how to make. It is therefore difficult to understand why the conversions would have been made in the first case in the heavy system, and in the second in the light system. The reverse seems more logical, the Akan buyer having to donate more gold to get the same product from the English merchant. To understand, let's analyze the sale of a trade gun. In 1820, the price of a Brown Bess rifle 7 was around £ 1. With an ozt of gold having a buying power of £ 4, it takes 7.8 g for £ 1. The Akan buyer had to pay 4 A* at 1.95 g or 32 T* at 0.24 g. The transaction was therefore done in the heavy system. In 1870, an ozt of gold had a purchasing power of only 3 £ 12 s, it took 8.8 g for 1 £. For the Akan buyer this amount corresponds to 5 A of 1.76 g or 40 T of 0.22 g. The transaction was then done for him in the light system. The switch from one system to another was therefore done simply, without the English trader realizing it and therefore not being able to report it. Our original article had highlighted the duality of the weights, but without being able to affirm, because of the heterogeneity in time and space of the collection on which our study concerned, that it was an integrated system weight to sell / weight to buy. This analysis of the sources confirms the plausibility of this dualist theory, which is, on reflection, more than the weight of the taku, the essential point of the Akan Weight System. What about the mitqal which Zeller claims to be not used in the Gold Coast, but which Garrard makes the cornerstone of the AWS. Could it be, like the weights corresponding to European weights, just one of the many facets of the Akan system, used in trade with North Africa? Let us summarize Garrard's thesis In the year 600, the weights and coins in use in the Mediterranean and Middle Eastern worlds were those of the Byzantines, inherited from the Romans, and those of the Persians, a distant heritage of the Greeks of Alexander the Great. Fifty years later, after having conquered a large part of these empires, the Arabs merged these Persian and Byzantine currencies into their bimetallic system. From the first they adopt the drachme, a silver coin which they make their dirhem, from the second the denarius aureus, a gold coin which they make their dinar. For weighing, they keep the Roman weight units in use. The 27.3 g uncia takes the name uqiya and the sextula, its sixth becomes the mitqal, which gives it the mass of 4.55 g. Weights and currencies meet at the level of the dinar and the mitqal 8, two terms that will end up meaning the same thing. This system reaches the Sahel via the Sahara, then the Akan, at the same time as the process of manufacturing the weights. The Akan would thus have imported a system based on the mitqal with as proof the discovery of very old weights, in terracotta, to this standard. They would then have adapted to European weights, as the Portuguese, Dutch and English arrived on the Gulf of Guinea coasts. Garrard, after a very documented historical account on the dinar, but ultimately unrelated to his conclusion, tells us that it would be this uqiya of 27.3 g, reduced, he does not say why, at 26.4 g, divisible into six 4.4 g mitqal and the so-called trading ounce, which is said to have been used in Sudan 9 for the gold trade 10. The problem is that we have not found a trace of a 4.40 g dinar or mitqal at any time in a North African country involved in the trans-Saharan trade. In Egypt, the starting point of the eastern caravans, the dinar, around 1200, weighs 4 g. In Morocco, where the northern come from, its nominal weight varies from 4.25 g around 1050 to 4.72 g around 1130 (see framed text and map). To find our way around, let's see schematically the course of an ounce of gold versus that of a load of salt around 1150, a date on which the Akan were probably already integrated into the trans-Saharan trade as gold producers: If this weight is nso-nsa (that is to say 7x3), the name that has come down to us, and if we keep at taku the value of 0.22 g in the light system, its value would have been 0.22 x 21 = 4, 6 g, which corresponds to an Almohad dinar with almost parity of purity, which is quite likely because Akan gold was considered very pure. So, how can we explain that nso-nsa, in every list of weights that we have studied, is given for 20 taku, a value which in our terminology should have been called nun-nan (5x4)?

7x3 = 20 or the crossroads of worlds Let's go back to our reasoning: The Portuguese use as a unit for weighting precious metals onça, in fact the ounce of Cologne, of 28.7 g, which is divided by 4, 8.16 and 32 but also by 24 which corresponds to one escrupulos of 1.16 g (Doursther, 1840). Four of these escrupulos weigh 4.64 g, exactly nso-nsa. As a result of this coincidence, the Akan would have had nothing to change in their habits to control the weighings of the Portuguese if they had, like the Dioula, used monetary weights. But, because it is easier when traveling, they used nested cup weights, each of which weighs half the previous one (see the detail of the painting by Quentin Metsys), with which it is therefore not possible to weigh 1/6 of ounce. You can only approximate it, by adding two cups of 1/8 and 1/32 = 5/32 (≈ 4,5 g). If we admit that they exchanged in mitqal, a unit known to both parties, the Akan, to adapt, went from their multiples by 3, 6, 12 ... to those by 2, 4, 8 ... and therefore from nso-nsa to nun-nan. The difference was small and from their point of view, it was a gain. As for the Portuguese, Akan gold was such a boon to them that, even if they had been aware of this subtlety, they would not have cared.. When, why and how did the confusion of names occur between the weight used with the Dioula and its surrogate with the Portuguese? We will never know, but we understand that through mixing, recombination and approximation, this semantic shift has occurred over the centuries. This mathematical incongruity would thus be the trace of the entry of the Akan into the first globalization, the crossroads of the European and African worlds. Thing are going as if the diversity of their weights has allowed the Akan to adapt to the Arab system in the same way they would later adapt to European systems. The mitqal would only be a guest, not the basement. As we progress in our investigation, the image of an autonomous and indigenous AWS becomes increasingly clear. However, it is difficult to think that it could have been born in the heart of the forest for the simple reason that there were no metals suitable for the manufacture of scales, without which weighing, even in seeds, could not have been possible. The Akan claim to be the descendants of the Wagadou 13, empire, a legend of which we do not know the part of the truth. Scales and weights were known there for the gold trade, which was already done with North Africa, and Abrus precatorius, whose red and black seeds make damma, as well as Parkia biglobosa, which the black seeds may be the taku, were growing there. The interpenetration between the Arab metal system and the African grain system was therefore able to take place there, before the Akan migrate south, towards the forest, to escape the Islamization imposed by the Almoravids.

|

|

Ben Rhombdane K., 1979. Supplément au catalogue des monnaies musulmanes de la Bibliothèque nationale: monnaies almoravides et almohades. Revue Numismatique, 21: 141-175. Binger L. G., 1892. Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi. Paris, Hachette, 2 vol. (vol. premier, 513 p.; vol. second, 414 p.). Bosman W., 1705. A new and accurate description of the coast of Guinea, divided into the Gold, the Slave, and the Ivory coasts. London, Ballantyne Press, 512 p. [Ed. Frank Cass, 1967]. Bouët-Willaumez L.-E., 1848. Commerce et traite des noirs aux côtes occidentales d'Afrique. Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 230 p. Bowdich T. E., 1819. Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, with a statistical account of that kingdom, and geographical notices of other parts of the Interior of Africa. London, John Murray, 512 p. [Ed. Frank Cass, 1966]. Dapper O., 2007 [1686]. Description de l'Afrique, contenant Les Noms, la Situation & les Confins de toutes ses Parties, leurs Rivières, leurs Villes & leurs Habitations, leurs Plantes & leurs Animaux ; les Mœurs, les Coûtumes, la Langue, les Richesses, la Religion & le Gouvernement de ses Peuples. Avec Des Cartes des Etats, des Provinces & des Villes, & des Figures en Taille-douce, qui représentent les habits & les principales Ceremonies des Habitans, les Plantes & les Animaux les moins connus. Amsterdam, chez Wolfgang, Waesberge, Boom & van Someren, 534 p., 42 pl. http://catalogue.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/cb34554868. Consulté en ligne en septembre 2017. De Marees P., 1605. Description et récit historial du riche royaume d'or de Gunea (sic), aultrement nommé, la coste d'or de Mina, gisante en certain endroict d'Africque. Amsterdam, chez Cornille Claesson, 100 p. [Les éditions Chapitre.com, 2017] Debien G., Delafosse M. & Thilmans G., 1979, Journal d'un voyage de traite en Guinée, à Cayenne et aux Antilles fait par Jean Barbot en 1678-1679. Bulletin de l'Institut fondamental d'Afrique noire (série B), 40(2): 235-395. Doursther H., 1840. Dictionnaire universel des poids et mesures anciens et modernes. Bruxelles, Hayez, 603 p. Garrard T. F., 1980. Akan weights and the gold trade. Legon history series. London, Longman, 393 p. Guilhiermoz P., 1906. Note sur les poids du moyen âge (première partie). Bibliothèque de l'école des chartes, 67: 161-233. Menzel B., 1968. Goldgewichte aus Ghana. Berlin, Museum für völkerkunde, Neue Folge, 12, Abteilung Afrika III, 241 p. Müller W. J.,1676. Die Afrikanische auf der guineischen Gold-Cust gelegene Landschaft Fetu. Hamburg, Zacharias Härtel (3e ed.) Perrot C.-H., van Dantzig A., 1994. Marie-Joseph Bonnat et les Ashanti-Journal (1869-1874). Coll. Mémoires de la Société des Africanistes. Paris, Société des Africanistes, 672 p. Roux C. & Guerra M.F, 2000. La monnaie Almoravide : de l'Afrique à l'Espagne. ArchéoSciences, revue d'archéométrie, 24: 39-52. Zeller R., 1913. Die goldgewichte von Asante (westafrika) eine ethnologische Studie. Leipzig, Teubner, 77 p.

|

|

|

Jean-Jacques Crappier |

| Crappier J.-J., 2020. A story of Taku and Mitqal. The akan weighing system, part three. Colligo, 3(1). |