The akan multiplication table. The akan weighing system, part two

La table de multiplication akan. Le système pondéral akan, deuxième partie

- Jean-Jacques Crappier & Pierre Gascou

|

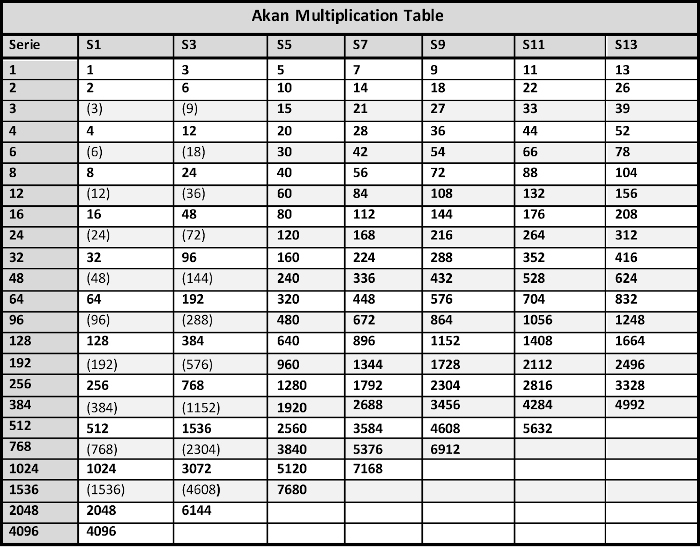

In addition to a previous communication which showed the sophistication and the African origin of the Akan Weighing System, this article explains how, by the compilation of previous works sometimes more than a century old, the authors understood that it's acted of a dualistic system light weight / heavy weight and reconstituted the multiplication table which underlined the value of its various units. These hypotheses having been demonstrated with a very high level of evidence by the study of thousands of weights. It remains to be understood how the Akan were able to perform multiplications as complex as, for example 13 by 192, without being able to write the operation. Keywords: akan - ashanti - baule - gold weight (goldweight, goldgewitch) - Ghana - Côte d'Ivoire - Gold Coast - dualistic system - ethnomathematics - Timothy Garrard - Henry Abel - Rudolph Zeller - Louis Binger - taku - ba - mitqal - proto-currencies En complément d'une précédente communication qui a montré la sophistication et l'origine africaine du système pondéral akan, cet article explique comment, par la compilation de travaux antérieurs vieux parfois de plus d'un siècle, les auteurs ont compris qu'il s'agissait d'un système dualiste poids-faible/poids-forts et reconstitué la table de multiplication qui sous-tendait la valeur de ses différentes unités. Ces hypothèses ayant été démontrées avec un très fort niveau de preuve par l'étude de milliers de poids, il reste à comprendre comment les Akan ont pu procéder à des multiplications aussi complexes que, par exemple 13 par 192, sans pouvoir, faute de numération écrite, poser l'opération. Mots clés : akan - ashanti - baoulé - poids à peser l'or - Ghana - Côte d'Ivoire - Gold Coast - système dualiste - ethno-mathématiques - Timothy Garrard - Henry Abel - Rudolph Zeller - Louis Binger - taku - ba - mitqal - proto-monnaies |

Weight classification according to Zeller (1869-1940)

Weight classification according to Garrard (1943-2007)

Weight classification according to Binger (1856-1936)

Weight classification according to Abel (1896-1958)

Does milligram precision make sense?

What do we know about the basic units?

What information can we get from these tables?

A very complicated Akan Multiplication Table! (Appendix 7)

How could the Akan, without written numbers, make such complex calculations?

|

This article is the second in a series devoted to the study of the Akan gold weights, well known to collectors and ethnologists, but whose functioning has given rise to little research and remains poorly understood. In our original article, we showed, by studying the largest collection of geometric weights ever studied (9031 including 298 chef's weights over 80 g) (Crappier et al., 2019), the organization and precision of this weighted system and invalidated the theory which made it derive from that of the Arabs, in favor of an African origin. Our reasoning assumes that the weight distribution has obeyed a complex multiplication table, which we had only briefly explained, so as not to weigh down our demonstration. Our purpose is to fill this gap here and show how this so-called Akan Multiplication Table was constructed and to think about the problems it raises.

To penetrate the Akan Weighing System (AWS), we have many lists of weights collected from the beginning of the 17th century by European merchants or explorers and field surveys carried out by Henri Abel and Timothy Garrard in the second half of the 20th century. But these lists, drawn up in Portuguese, Dutch, English or French units, are more or less exact and complete, and the field surveys suffer from having been carried out several generations after the Akan stopped using them. Data interpretation is complicated by great linguistic variability and a gradual tangle over time. It is therefore not surprising that the authors who studied it during the 20th century, all came to different conclusions about the nature and functioning of AWS, and that the work ended there. Despite the passage of time and the uncertainty about data, it seemed possible to propose a synthesis of the different theories from four main sources which are in chronological order the publications of Louis Gustave Binger in 1892, of Rudolph Zeller in 1903, by Henri Abel from 1952 to 1973 and by Timothy Garrard in 1982. We have dissected the lists of weights reported by these authors to understand their structure. We translated them in the form of tables that an overview is enough to understand the reasoning that led us to the Akan Multiplication Table. The interested reader will find more detailed information in the framed texts.

The weight lists allow us to get a precise idea of the relationship between them of the main Akan weights denominations, but as they are established, for the most part, in monetary equivalent value, they do not give us directly the corresponding mass. To calculate it, we must therefore know the price at which an ounce of akan gold was negotiated, knowing that these ounces, like currencies, differed from one country to another, that the fine metal content was variously appreciated by Europeans traders, and that it varied depending on whether it was gold dust or nuggets. There were 3 kinds of units: - Basic units which rest on seeds, the ba, and the taku 1, in a ratio between them of 3 ba for 2 taku. The ba is worth 2 damma, that is to say two seeds of Abrus precatorius, a forest liana. Taku is also a seed, but its exact nature is unknown to the authors; - Ake 2 is another frequently cited unit, given for 1/16 of an ounce. An ake is worth 8 taku; - The benna 3 which is worth 2 ounces, whether Portuguese, Dutch or English, is therefore worth 256 taku. Typically, the name akan of weights is formed by a radical (ba or taku for small units) followed by a suffix which can mean either a "multiplication by", or more rarely an "addition of". There are thus around twenty radicals and their multiples by 1/2, 2, 3 or 4, sometimes up to 8, corresponding to around sixty different weights.

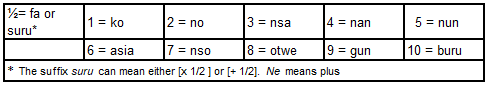

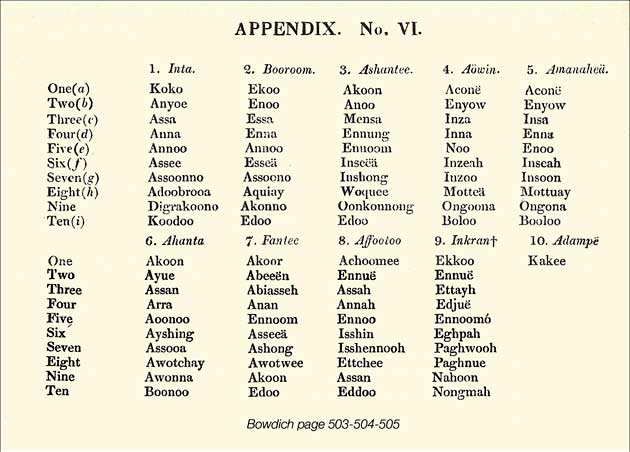

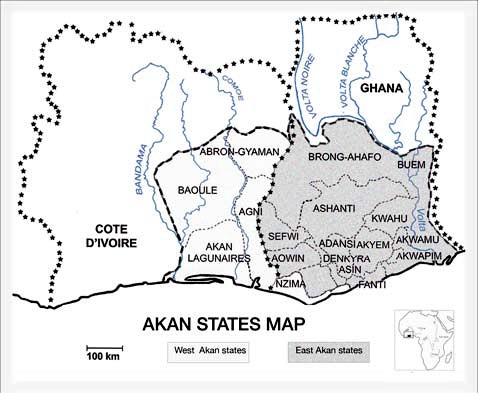

Although they belong to the same linguistic group, the Akan languages differ significantly from one state to another and the names of the weights vary, in particular between eastern and western states (see map), or take different values. To facilitate the comparison between the different sources, we have simplified and standardized the Akan numeration (Table 1). For more information, the reader will refer to Appendix 1, reproduced from Bowdich, which shows all its complexity (Bowdich, 1819). We have used Ashanti names for Eastern Akan lists and Baule names for Western Akan lists, with their simplest spelling since the European translation is arbitrary. To avoid confusion, the word weight will henceforth be reserved for the designation of objects, and the word mass for their value in grams.

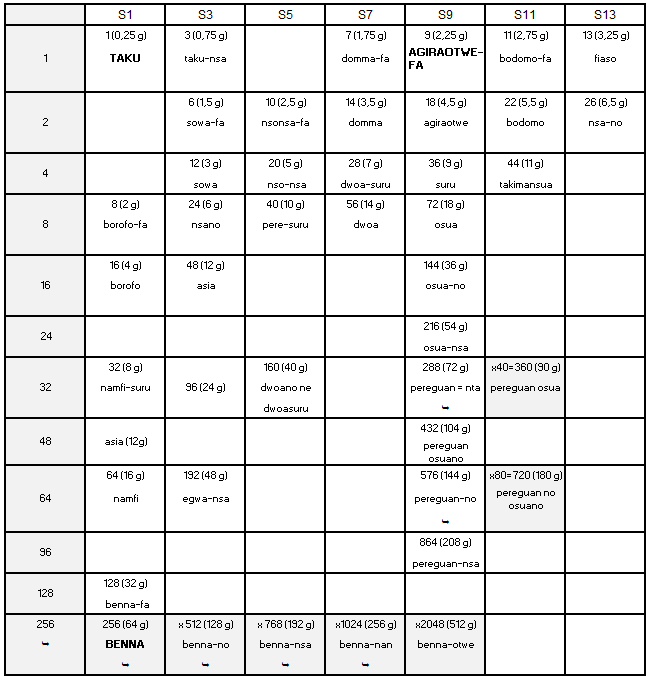

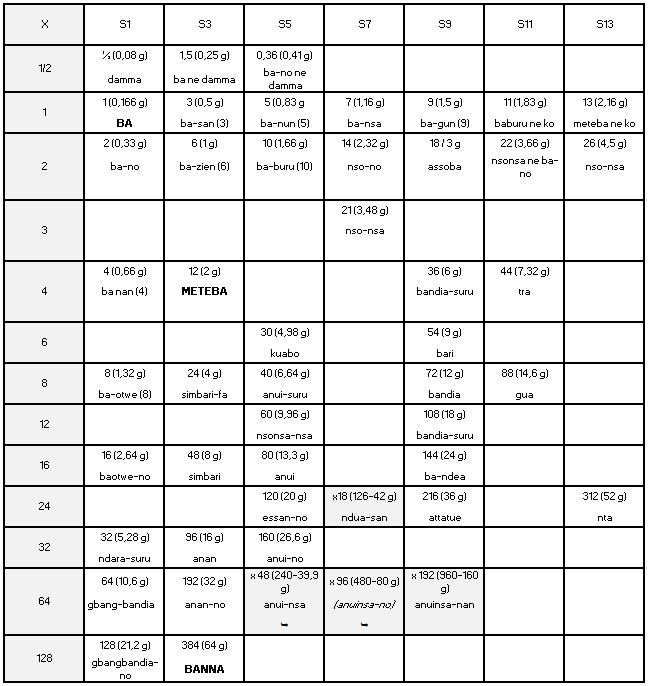

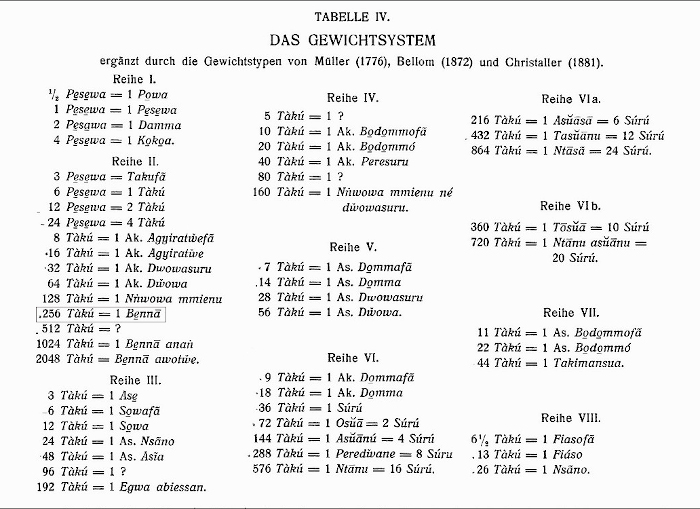

Weight classification according to Zeller (1869-1940) Rudolph Zeller, director of the ethnographic section of the Historical Museum of Bern is the first, in 1913, to publish a synthesis of the Akan Weighing System, from information provided by Rudolph Bürki, a Swiss missionary who lived in Gold-Coast 4 at the beginning of the 20th century, and from older lists established when the weights were still in use. The data are of Akyem and Ashanti origin, so eastern akan. Zeller's system is based on the taku, whose weight he calculates at 0.25 g. He doesn't talk about ba. He distributes the weights into 8 series 5, the main 7 of which have 1,3,5,7,9,11 and 13 taku as their first term, and each element of which is double the previous one. He presents his results in the form of a table (Appendix 2) which can easily be transformed into a multiplication table composed of 7 columns, one per series, the first weights of which are respectively 1,3,5,7,9,11 and 13 taku, and of a dozen lines corresponding to multipliers by the powers of 2, that is to say 2,4,8 and so on until 2048 for series 1 (Table 2).

Zeller also claims that the mitqal 6, the weight of Arab origin which represents the mass of a dinar 7, was not used in the Gold Coast and reports the testimony of Christaller affirming that the Akan used different weights to buy or sell (Zeller, 1903).

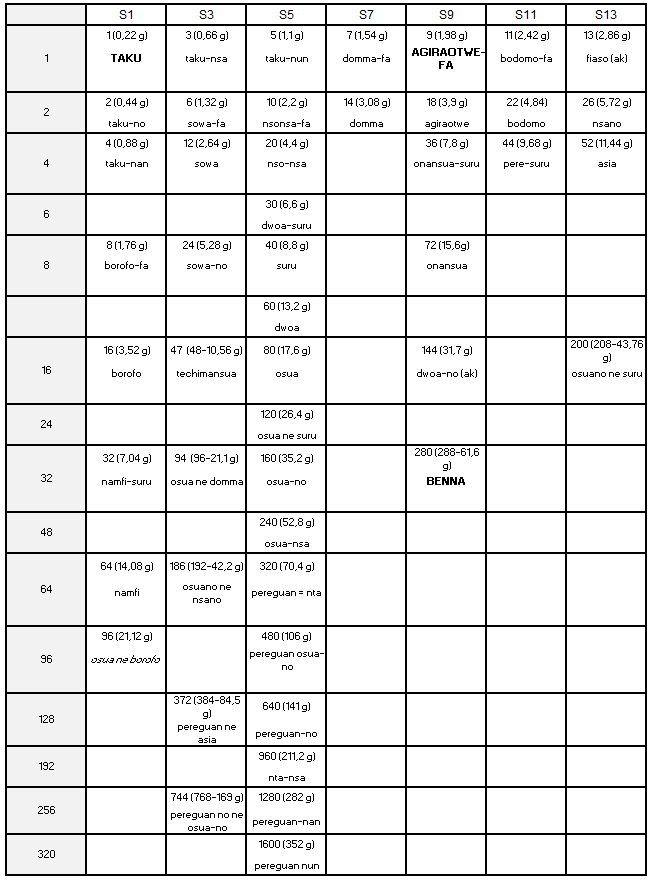

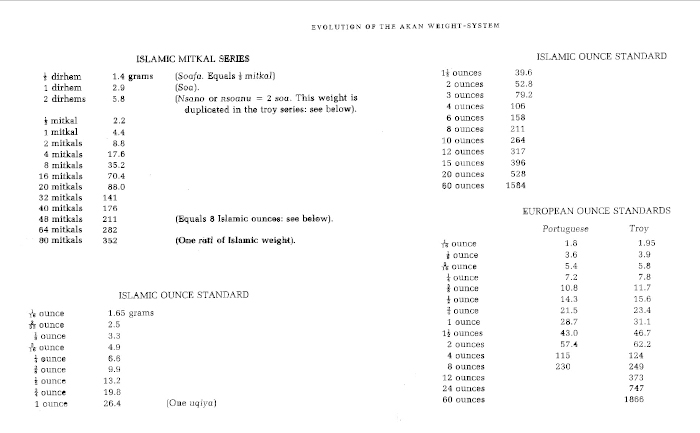

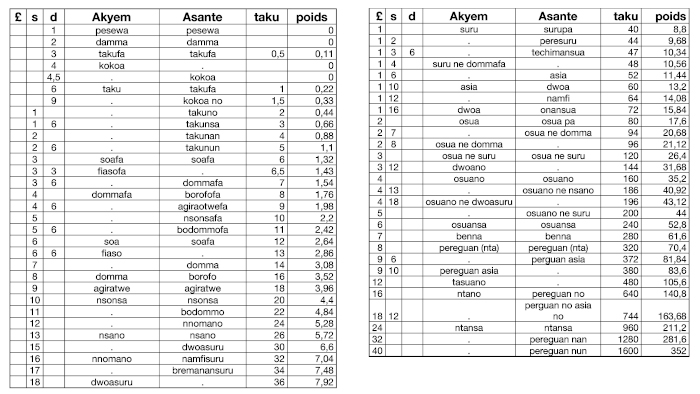

Weight classification according to Garrard (1943-2007) An English native, Timothy Garrard spent most of his career in Ghana as a lawyer and ethnologist. His work is authoritative in terms of Akan weight. His theory contradicts that of Zeller. For him, the AWS is a loan from the Arabs, the basic unit of which was the mitqal of 4.4 g and the uqiya, the Arabic ounce, of 26.4 g. The Akan are said to have learned from the Dioula, a caste of Islamized Soninke merchants, who traded with the two parties in the context of the trans-Saharan trade. They would later have added European weights to it, once contact had been established with them, thus explaining the complexity of the system, which he said consisted of four series, two modeled after the Arab weights (one on mitqal, the other on uqiya), one on the Portuguese weights, and the last one on English weights, each weight being, in a series, twice the previous one (Appendix 3). The uquiya series is said to have been used mostly among western Akan. The taku, to which he attributes the mass of 0.25 g like Zeller, and the ba, would have played only an ancillary role for small transactions. He does not find a trace in his investigations of the difference between weight to sell and weight to buy (Garrard, 1982). This thesis is well argued, but is contradicted by the lists of weights which he himself collected in the various Akan states from notables who still knew their names and their counter values in English currency. None of them cites mitqal, but all report a 6 pence taku weighing 0.22 g. The summary table which he establishes from the lists of 16 different states is too large to be carried over here. We only cite (Appendix 4) the Ashanti and Akyem lists which allow to find, on the basis of a taku of 0.22 g, the seven series of Zeller, and to reconstruct, albeit in a different order, a multiplication table (Table 3).

Weight classification according to Binger (1856-1936) Captain of the Marine Infantry, Louis-Gustave Binger explored West Africa. He ended his career as governor of Ivory Coast. The account of his trip from Niger to the Gulf of Guinea is our third source (Binger, 1892). Precisely that of his stay in 1889 in Agni country, a western Akan people, of which he wrote down the list of weights (Annex 6). It is established on the basis of an ounce rounded to 32 g, and a price of 3 francs per gram of gold ore. The basic unit is the ba which is worth 50 c and therefore weighs 1.66 g. (It is equivalent to 2/3 of the 0.25 g taku). The mass of the damma seed must therefore be 0.83 g. This list can, like the others, be transformed in a multiplication table (Table 4), on the model of that of Table 2.

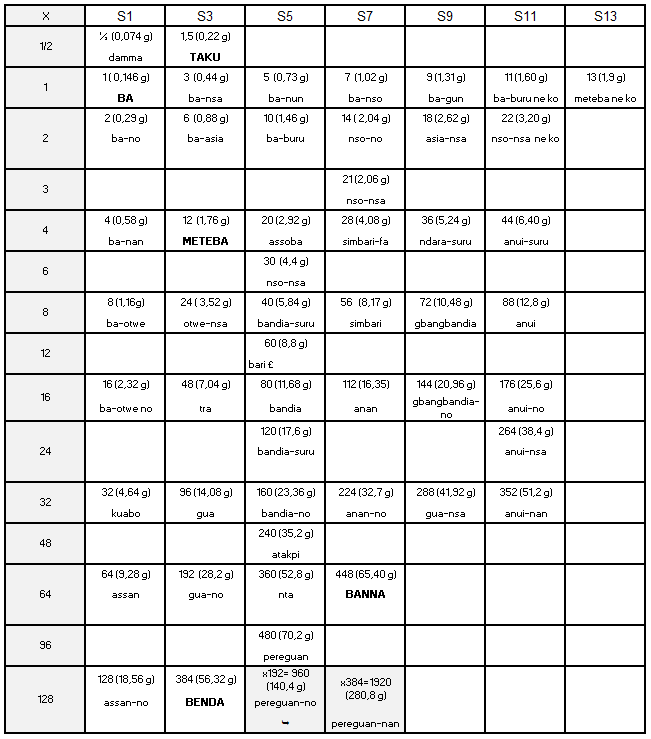

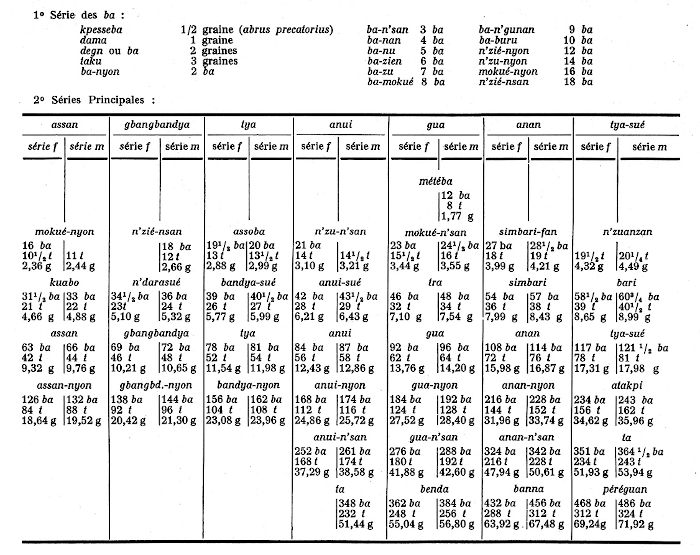

Weight classification according to Abel (1896-1958) French colonial administrator, Henri Abel was Mayor of Abidjan from 1948 to 1952. His field investigations in 1952 in Baule, Agni and Aboure countries, therefore in the Western Akan area, enabled him to meet notables who still had weights, who they no longer knew how to use, but whose names and values they knew in Fr or in £. His informants report to him a system based on taku and ba and comprising for each unit male and female weights (Abel, 1973). The analysis of their appellations allows him to classify them into seven series like Zeller and, by weighing them, to calculate the mass of ba and taku, respectively 0.146 g and 0.22 g (in the ratio of 3 to 2). The idea of transforming the lists into a multiplication table came from him, but the one he establishes, both in ba and in taku, is complex and wobbly (Appendix 7). Reconstructed with 1,3,5,7,9,11,13 ba as the baseline, it finds a coherent structure according to the model of Binger (Table 5).

Four documented and credible sources, four different units, contradictory interpretations, but four tables from which lessons emerge on the Akan weighting system: - The possibility to distribute the weights in 7 series, within which each unit is the multiple by 2, sometimes by 3, of the previous one; - The preferential use of ba in the western states and taku in the eastern states; - The coexistence in each region of light units and heavy units: in the west a light ba of 0.146 g and a heavy ba of 0.166 g, in the east a light taku of 0.22 g and a heavy taku of 0, 25 g, in a light to heavy ratio of 8 to 7; - Different appellations between western and eastern peoples, but which within each region are common to light and heavy weights. Sometimes with constant value (the weights of the same name have the same number of seeds but a different mass), sometimes with constant mass (the mass is constant but the number of seeds is different). We conclude that the Akan, whose daily payments were made of gold dust, probably used, as Abel said, who was however mistaken about its nature 8, a dualist system of light weight / heavy weight based on the difference between light and heavy seeds: light ba and taku (now denoted B and T) to buy at low price, or make a loan, and heavy ba and taku (denoted B * and T *) to resell at high price or recover a debt with interest. We also deduce a multiplication table common to the 2 regions and to the light and heavy subsystems by compiling tables 2, 3, 4 and 5, by filling in the missing boxes and by adding multipliers by 192, 384… 1536 which we let's call Akan Multiplication Table (Appendix 7). In doing so, we predict values unknown from our sources but which we should find by weighing the weights that we have collected, in particular that of the 298 chef weights.

Even if we were able to show in our original article, with a very high level of evidence, the plausibility of our conclusions, the Akan Multiplication Table nonetheless raises many theoretical and practical questions: 1. Does milligram precision make sense? It is obvious that such precision was inaccessible to the Akan, given the rusticity of their scales, but it should be remembered that these are calculated values and not actual values. This did not prevent them from using an even lighter unit than ba, the pesewa, corresponding to a grain of rice, weighing 0.04 g. This precision in the calculations is however necessary because if the rounding in the value of the ba and the taku has only little consequences for small and up to medium values, they cause from benna a significant drift, drift that we do not find during the weighing of the chef's weights and which therefore did not exist in reality. This is understandable since the larger the number of seeds, the closer we get to their average value and therefore the more precise the measurement. 2. What do we know about the basic units? - What is the nature of ba and taku? If ba is correctly identified with the seed of Abrus precatorius, there is a doubt on its exact weight. The seed that corresponds to taku is not known. We come back to this in detail in a dedicated article 9. - What do we know about ake? Worth 1/16 of an ounce, it does not appear under this name in the weight lists that we have studied. It corresponds to the weight that the Akan called metaba in western countries, agiraotwe-fa in eastern. The origin of the word is controversial 10. Our opinion is that it comes from the word aquiay, which in Brong Ahafo country (alias Booroom, see map and Appendix 1), corresponded to the number 8 and which is said in the other dialects otwe, or awotwe, or even oque, in the account made by de Marees of the Gold Coast (de Marees, 1605). Thus ake would simply mean 8 taku. We are therefore dealing with a light ake of 1.79 g (denoted A) and a heavy ake of 1.94 g (denoted A *). - What about the benda? Benna in eastern states, banna or benda in western, every author gives him the value of 2 ounces and the weight of 62 g in one or the other light or heavy system. Abel is the only one to distinguish between a 56 g benda and a 65 g benna. We will discuss it again. This unit is not attached to a seed. 3. What information can we get from these tables? Do Ba and taku have a different origin? If we admit that the presentation in multiplication table had a real meaning for Akan, the fact that they are calculated in taku in eastern regions, and ba in western, is an argument in favor of a geographical separation of the two systems, although taku and ake were also used in western states. Tables, however, tell us nothing about the precedence of one system over the other.

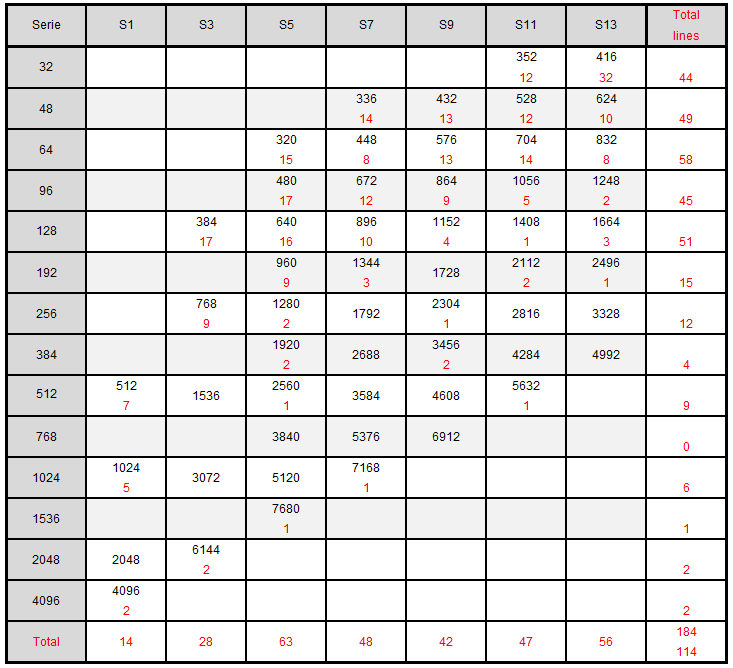

Which of the light or heavy systems would have preceded the other? There are several clues in these lists that allow us to discuss it. Thus, the almost perfect regularity of tables in T* compared to the apparent disorder of tables in T pleads for an anteriority of the first compared to the second. It is to ignore that one of the first reports of the Akan weights, by de Marees, which dates from 1605, reports an ake of 1.79 g and a benda of 57 g, belonging to the light series, and that nso-nsa, which corresponds to mitqal and therefore to the trans-Saharan trade, which is even older, also comes under this system. We must therefore consider a coexistence and interpenetration of the two systems. Can we conclude that the two systems coexisted? Just as ba predominated in western states, and taku in eastern, one might think that the differences between light and heavy weights corresponded to regional peculiarities. For Ott, this was the case between the coastal states and those in the interior. He saw in it the way in which African importers, who went to the forts on the coast to buy from Europeans traders the commodities which they redistributed in the land, took their profit (Ott, 1968). But weighing gold dust with the scales, spoons and containers held by the Akan is difficult, and adding a weight during weighing takes the risk of compromising a precarious balance and losing gold. We can therefore hypothesize, with Abel, a dualistic system used daily in each state. To imagine how it could have worked, we have to distinguish two cases. First, a direct transaction between producer and consumer, in which only the price asked by the seller intervenes, corresponding to a quantity of gold dust usually fixed by custom and indicated by the name of a weight. Negotiation involves the quality and weighing of gold, each using their own weights to verify the transaction. Only one weight system is required in this case. The second situation is that of a loan, or a resale by a merchant, in which the dualist system takes on its full meaning, the merchant, or the lender, using light weights to buy the goods, or to make the loan, and heavy weights to resell it or recover the debt. The difference in gold dust between weight to sell and weight to buy representing their profit. Then two questions arise: - Is the profit margin of 1/7 (14%) consistent with this assumption? This rate seems suitable for a loan, and even usurious in an economy without inflation. For a sale on the other hand, the profit seems very low, except if we take into account the fact that Akan people knew neither VAT, nor social charges, and that their structural costs were low. 14% of net profit at the end of the year would satisfy more than one trader these days. Furthermore, with regard to trade with the Arabs or the Europeans, internal demand was such that the intermediaries, whether Dioula or Akan, had probably found a way to take a greater profit, either by reducing the quantities further , or by increasing prices anyway. Only three of them refer to it more or less explicitly, but most do not mention it. We will discuss about this in a next article 11. This system being intended for transactions between Akan, there was no reason why foreigners, who were paid in gold, for goods whose price they calculated according to supply and demand, should have been informed. The diversity of Akan weights was such that they only had to know, from the system, that part which corresponded to their own monetary weights: light for the mitqal, uqiya and onça, heavy for Dutch and English Ozt. 4- A very complicated Akan Multiplication Table! (Appendix 7) - We only have 10 fingers to count. Series 11 and 13 therefore seem counter-intuitive. Do they really exist? - Why all these additional values compared to our sources? Are there missing units used among them by the Akan but unknown to their European partners? - Does the predominance of multiples of 2 in these tables result from an observation bias, linked to the use by European merchants of nested cup weights which are designed on this principle 12. The study of the 298 weights above 80 g, known as Chiefs’ weights, allows us to answer these three questions in the affirmative: - Table 6 shows the boxes in which they are distributed according to the value to which they are closest after transformation into T or T *. Series 11 (47 weights) and 13 (56 weights) are particularly well represented and their existence is therefore in no doubt. - Of the 55 boxes provided for weights over 80 g (at least 320 T *) 14 only are not occupied. There were therefore many weights unknown by Europeans whose existence can be predicted by the Akan Multiplication Table. - There are 114 weights in lines 48, 96, 192 and so on, that’s to say 38% of the chief's weights that cannot be weigh with nested cup weights. Their small number in European sources seems to be due to a bias, potentially linked to the use of these cup weights.

5- How could the Akan, without written numbers, make such complex calculations? Their language allowed them, with a lot of circumlocution, to formulate numbers greater than 100, but how did they perform operations as complicated as 13 x 192 = 2496 in the absence of written support 13? how did they pass on their knowledge? Can we consider with Abel that the decorations of the geometric weights had a numerical meaning? We think so, and we are able to decipher many weights, but we have not found any reproducible structure in their coding, which is more like a rebus than an ordered numeration. We don't know how they did it, but we know they did it, since the weights are there to testify it, and that we have proven that their distribution was not due to chance. One way to circumscribe the problem is to assess the number of people involved. On a population of 1,400,000 Akan on the eve of colonization, Garrard evaluated the possessors of weight at 60,000, sharing a cumulative production over the centuries of three million weights, thus fifty each, and the number of goldsmiths in activity to a hundred. It was therefore a social and professional elite. If the owners of weights would easily memorized their value, the goldsmiths, whose Garrard estimates annual weight production at 100, could be the only ones to know all the subtleties. One can nevertheless wonder if this multiplication table was really used as a means of calculation and if it is not a mathematical artefact, linked to the geometric structure of the series of weights, which appears when we translate into our units. If this were the case, this would open up the possibility of alternative calculation methods, as ethno-mathematicians have studied, for example, among the Siamou in Burkina-Fiaso (Traoré, 2008). But that does not change the value of what we have called the Akan Multiplication Table as a tool to unravel the skein of Akan gold weights. |

|

This article allowed us to explain how we built the Akan Multiplication Table from multiple sources, to detail its intricacies and to discuss its relevance. It is not ultimately excluded that it is the result of a mathematical bias that we are not qualified to demonstrate. But, since the quality of a scientific theory is judged by the predictions it allows, we consider that this one, with which we have both proved the dualism of the Akan Weighting System and predicted the distribution of chief’s weights, is the one who describes it the best, except to discover how the Akan would have proceeded differently to calculate their weights. The floor is open to ethno-mathematicians. |

|

Abel H., 1952-1959. Déchiffrement des poids à peser l'or en Côte d'Ivoire. Journal de la Société des Africanistes, 22: 95-114 (1952); 24: 7-23 (1954); 29: 273-286 (1959). Binger L. G., 1892. Du Niger au Golfe de Guinée par le pays de Kong et le Mossi. Paris, Hachette, 2 vol. (vol. premier, 513 p.; vol. second, 414 p.). Bowdich T. E., 1819. Mission from Cape Coast Castle to Ashantee, with a statistical account of that kingdom, and geographical notices of other parts of the Interior of Africa. London, John Murray, 512 p. [Ed. Frank Cass, 1966]. Crappier J.-J., Farinetto C., Gascou P., Maunoury C., Maunoury F. & Mateusen G., 2019. The Akan Weighing System restored after 120 years of oblivion. A metrological study of 9301 geometric gold-weights. Colligo, 2(2). https://perma.cc/H494-E42R De Marees P., 1605. Description et récit historial du riche royaume d'or de Gunea (sic), aultrement nommé, la coste d'or de Mina, gisante en certain endroict d'Africque. Amsterdam, chez Cornille Claesson, 100 p. [Les éditions Chapitre.com, 2017] Garrard T. F., 1980. Akan weights and the gold trade. Legon history series. London, Longman, 393 p. Mollat H., 2003. A new look at the akan gold weights of west Africa. Anthropos, 98: 31-40. Niangoran-Bouah G., 1984-1987. L'univers Akan des poids à peser l'or. Dakar, Nouvelles Éditions Africaines, 3 vol. (Vol. I: Les poids non figuratifs, 1984, 316 p.; vol. II: Les poids figuratifs, 1985, 320 p.; vol. III: Les poids dans la société, 1987, 328 p. Ott A., 1968. Akan gold weights. Transactions of the Historical Society of Ghana, 9: 17-42. Traoré K. & Bednarz N., 2008. Mathématiques construites en contexte : une analyse du système de numération oral utilisé par les Siamous au Burkina Faso. Nordic Journal of African Studies, 17(3): 175–197. Zeller R., 1913. Die goldgewichte von Asante (westafrika) eine ethnologische Studie. Leipzig, Teubner ed, 77 p.

Annex 1: The different akan numerations (Bowdich, 1819)

Annex 2: Zeller’s table IV

Annex 3: The four Garrard’s series

Annex 4: Ashanti and Akyem weight lists according to Garrard

Annex 5: Agni appellations for gold, according to Binger

Annex 6: Abel’s table.

Weight appellations are Baule. This table is complicated by the presence of male (m series) and female (f series) values, the difference between which is too small to be operative. It is also wobbly because Abel dos not take as base units 1,3,5... 13 taku, but intermediate values, those whose names would have been the most used, with their multiples and sub-multiples. This gives an irregular progression, passing in taku from a reason 6 to a reason 8 as follows: 42 (assan), 48 (gbangbandya), 52 (tya), 56 (anui), 64 (gua), 72 (anan), 80 (tyasué). In addition, these weights should not be on the same line because they are not multiple from each other. The table becomes coherent again, when it is reconstructed in ba, taking as base units 1, 3, 5… 13 ba and changing the order of the columns (Table 5). In ba rather than in taku, because the names of several weights in the first line show that they are multiples of ba (mokué-nyon = 16, n'zié-nsan = 18, n'zu n'san = 21, mokué n'san = 24.

Annex 7: Akan Multiplication Table

|

|

|

Jean-Jacques Crappier

|

| Crappier Jean-Jacques & Gascou P., 2020. The akan multiplication table. The akan weighing system, part two. Colligo, 3(1). |